Cracking the mystery of China's seed-eating habit

In 2015, a Chinese governmental official was reported eating guazi (瓜子), or melon seeds, at work, which caused public outcry and his punishment. Why? Well, in China, guazi isn’t just any snack. You’ve got to work to get the guazi out of their shell, so the act of eating guazi is symbolic of killing time—or, in this case, a symbol of wasting taxpayer money.

In Chinese, there is even a word describing the act of shelling guazi—嗑 (kè), loosely meaning “to crack guazi with the front teeth.” It may sound easy, but if you crack too strongly, you crunch the seeds and shell into your mouth.

There is no proper explanation for why Chinese people like eating guazi. Some say it’s all about frugality, others say that it’s due to the cold weather of North China where people would sit on the kang (a heatable brick bed), eat guazi, and chat all day long. Another interesting theory says that the habit was picked up from Russians in the late Qing Dynasty in northeastern China. At the time, Chinese called Russians “老毛子 (old hairy one),” a disparaging term based on their abundance of hair, so guazi was also named “毛嗑儿 (máokèr),” meaning “things the hairy barbarians like to crack”.

Guazi literally means melon seeds but broadly refers to three kinds of edible seeds: watermelon seeds, pumpkin seeds, and sunflower seeds. Though all the three were brought to China from foreign lands, China has a long history with them.

The earliest record of guazi appears in Taiping Huanyuji, a geographical record completed between 976 and 983 AD, but there is no strong evidence to confirm which type of seed it was. It is believed that watermelon seeds were the earliest to become popular in China, traceable to as early as the Yuan dynasty and was very common in the Ming and Qing dynasties.

There was a folk ditty popular in the late Ming dynasty, describing a girl sending a bag of shelled guazi to her lover:

“The guazi is not a precious thing,

But I have shelled them one by one on the tip of my tongue;

Wrap them in a handkerchief,

Send them to my dear lover;

The gift is trifling,

But contains my deep feelings;

So when you accept this,

Please don’t forget me.”

Maybe the thought of getting a handkerchief full of guazi touched by someone’s tongue is a little disgusting, but we all do dumb things for love.

Even in the imperial court, melon seeds were well loved. According to the Zhuozhongzhi, records about imperial life written by the eunuch Liu Ruoyu in the Ming dynasty, Emperor Shensong “loved eating fresh watermelon seeds baked with salt.”

While watermelon seeds were the last word in seeds before the Qing dynasty, pumpkin and sunflower seeds soon came into the mainstream. French Catholic missionary priest Abbé Huc, who traveled in many places in China in the middle of 19th century, wrote in his book,

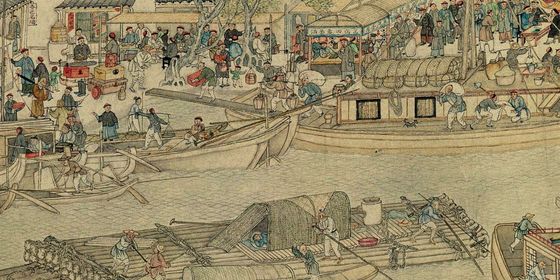

“The Chinese have a special love for melon seeds, so watermelon is indispensable in China…in some areas, after the harvest, the watermelon is no longer valuable, and people keep them purely for the seeds inside. Sometimes, large amounts of watermelon are brought to a busy street and distributed to the passers-by for free, on condition that they leave the seed to the owners…cracking melon seeds is a daily consumption in China’s 18 provinces, it is really interesting to see people eating them as appetizers…when people get together to enjoy tea or drink alcohol, there will absolutely melon seeds on the table. People crack melon seeds when they travel; whether a child or an artisan, if they have a few coins in their pocket they will spend it on this snack. On a major road or small lane, you can buy [melon seeds] anywhere. Even in the most deserted areas, you need not worry that there will be no melon seeds available…sometimes, when you see flat-bottomed barges sailing the rivers loaded down with this precious cargo, you honestly feel like you have come to a kingdom of rodents.”

In the Republican era, famous painter and essayist Feng Zikai (1898-1975) depicted the habit of his era’s seed-eaters in his article “Eating Guazi”: “On the banquet or in the teahouse, I haven seen countless masters of cracking guazi. Recently guazi has been selling well, even the kids managed this great techniques.” But Feng hated this time-killing custom, regarding eating guazi as a symbol for the deep-rooted illness of the nation. He wrote: “Except for smoking opium, there is no better way to kill time than eating guazi, because it has three characteristics: you can never have too much, you will never feel full, and you have to shell them first…If this custom develops, I’m afraid the whole nation will perish amidst the sound of cracking and spitting.”

It didn’t exactly work out like that.

Though eating guazi is truly, mindlessly time-consuming, some people believe it is a necessity in social interactions. When you visit someone’s house and the host offers you some guazi, it helps to make the situation relaxed and less needlessly formal (or at least, it solves the problem of what to do with your hands while you talk). At a banquet, before the dinner formally begins, being served some guazi and tea makes waiting for dishes much more bearable and prevents awkward stomach-growling.

According to Quan Yanchi’s literary non-fiction work Leaders Around the Dining Table, Chairman Mao loved eating watermelon seeds; Liu Shaoqi, former president of China and Vice-Chairman of the Communist Party of China from 1956 to 1966, liked sunflower seeds. “When they have a meeting at night, Mao could build a Baota mountain [iconic mountain in the former revolutionary base of Yan’an] with his seeds shells, while Liu would make a Mongolian yurt.”

Nowadays, guazi is still one of the most popular snacks in China, you can see people cracking guazi everywhere—on a train, at a banquet, and even in the cinema. Just remember to take your friends up on the offer of guazi; friends who crack together stay together.