A sexual harassment claim against a female supervisor leading to a suicide ignites controversy over China’s veneration of teachers

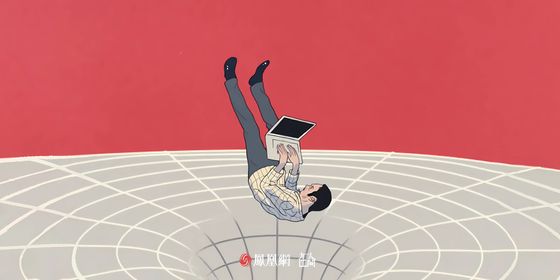

Yang Baode, a 29-year-old PhD student from Xi’an Jiaotong University, recently made headlines after killing himself on Christmas Day. But Yang wasn’t lonely or depressed because of the holiday season: Yang’s girlfriend explained on Weibo that Yang had drowned himself because he “couldn’t suffer being enslaved by his PhD supervisor any more.” She posted WeChat messages between Yang and his supervisor as proof.

The chat records showed that Yang was treated as a gofer by his supervisor: Watering her flowers, cleaning the office, carrying bags, picking up her car, accompanying her to visit supermarkets, buying her lunch and eating together, doing housework, attending banquets to prevent her getting drunk, and so on. The supervisor, surnamed Zhou, also asked Yang to comment on her dress sense, saying “I remember this coat is your favorite,” and told Yang that she felt Yang’s girlfriend was not a good match for him.

While netizens were enraged by the clear abuse of power and suspected sexual harassmenet, Liuliu, a well-known screenwriter, decided go against public opinion, commenting: “What are today’s kids thinking about? You just install curtains, do some grocery shopping, clean the room [for the teacher] and you feel hurt to death? [Speaking] as a kid from the countryide, this is too self-important…Isn’t it your duty to serve your teacher?” Liuliu also mentioned that, back in her teacher-serving days, they all would “carry the bag, hold cups, deal with all check-in procedures, and do washing for the teacher, and still worried the teacher may not be satisfied.”

Unsurprisingly, Liuliu’s opinion incurred some wrath. People commented that: “You have just got used to being a slave and can’t stand up any more!” But Liuliu’s evocation of “tradition” student-teacher relations has a long feudal history.

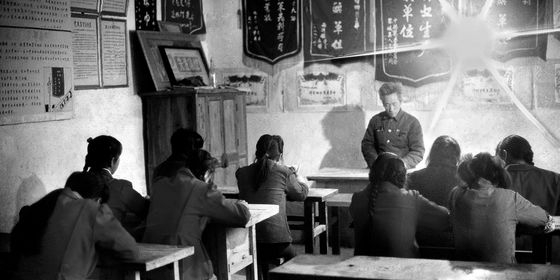

In ancient China, teachers enjoyed superior social status. In Confucianism, a teacher is among the five subjects of worship, ranked just after heaven, the earth, the emperor and parents. A household saying puts it : “一日为师,终生为父 (Once a teacher, always a father),” meaning that students should respect their teacher as much as their father. One Han Dynasty tale evokes the story of the PhD student.

According to History as a Mirror, a Song Dynasty record of Chinese history from 403 BCE to 959 CE, there was a young scholar named Wei Zhao, who wanted to become a student of Guo Linzong, a famed scholar of the time. Wei volunteered to be the scholar’s dogsbody. Once when Guo was sick, he ordered Wei to boil some porridge for him. Guo wasn’t satisfied with whatever Wei cooked up, and threw the bowl to the ground, saying: “You made porridge for the elder, but didn’t pay any respect. That makes the porridge inedible!” So, Wei made another bowl; Guo threw it away again. After the fourth attempt, Guo said to Wei: “Previously, I only know your appearance. But now, I know your heart.” It was all a test, you see! Guo then taught all his knowledge to Wei.

This story has long been used a good example of why to respect teachers: The teacher made his unreasonable requests and bad temper to examine Guo; the student passed; happy ending. Nearly 2,000 years later, no one seems to have asked the question, “Is such a test fair?” How could the teacher just assume that Wei should cook porridge for him again and again? Isn’t it too much to demand such respect? What if Wei’s tolerance was a little less, and said no to the moody teacher? The most possible result may be that Wei would expelled and people would say he deserved it.

Maybe, before we discuss how students should respect teachers, we should first think about the definition of “teacher” again. Han Yu, a famous scholar in the Tang dynasty, defined the role in his classic article “On Teachers”: “A teacher is one who propagates the doctrine, imparts professional knowledge, and resolves doubts.” It is a sacred and important job, but many are more than happy to take it too far.