China’s middle-aged actresses are speaking out about age discrimination

When Song Dandan appeared on variety show The Birth of a Performer in 2017, the beloved actress discussed her decade-long absence from the screens: “After I got to 35, nobody wanted to cast me anymore,” the then 56-year-old Song lamented.

Song, a veteran of CCTV’s Spring Festival Gala, was renowned for her roles in the groundbreaking 1990 sketch “Excess Birth Guerilla” and 1994 TV series I Love My Family. Her troubles, though, started in middle age. After she played a re-married mother in the hit 2005 sitcom Home with Kids, Song discovered that there were only two types of roles she could find: meddling mothers, and meddling mothers-in-law. “I was anxious [about my career],” she told Chinese Business View. “But the anxiety lasted so long that I got used to it.”

In 2017, Song grayed up for a new role—meddling grandmother in the series Wonderful Life. This time, her character’s son was played by Zhang Jiayi, an actor just nine years her junior. As 47-year-old actress Tao Hong once complained in an interview with Sina Entertainment, “Not only in China, but all Asian cultures, there is a preference for ‘youthful girls.’ At my age, it’s rarer and rarer for me to be offered interesting roles.”

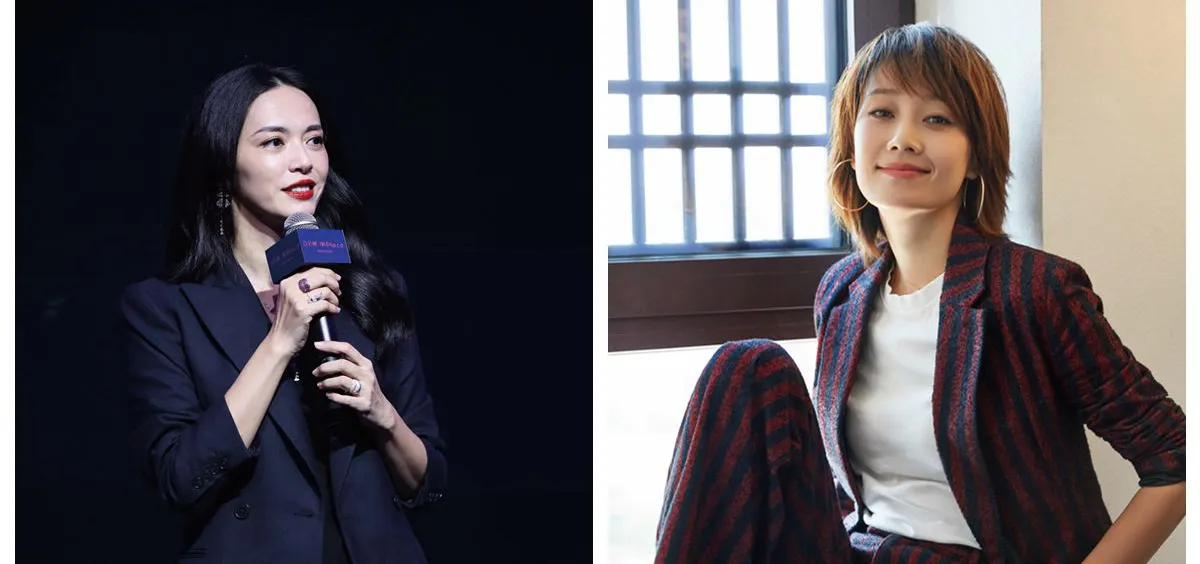

Actress Zhou Xun

It’s a tale as old as showbiz itself: the actress who find herself “aged out” of the business before she even reaches her 40s. A lack of older female representation on screen has always been a problem, but the situation is particularly dire in China, where a youth-obsessed entertainment industry vastly prefers young actresses over middle-aged ones. Those at the prime of their craft are often dismissed as visually unattractive by casting executives.

To add further insult, the industry’s “midlife crisis” mainly affects female performers. Women face the double discrimination of ageism and sexism, stuck in domestic roles while aging male actors enjoy parts as “charming uncles” or older lovers to besotted starlets: 41-year-old Julian Cheung romancing 23-year-old Fu Mengni in 2012’s Born to Love You; 50-year-old Wu Xiubo’s partnering with 29-year-old Yang Ying in 2018’s City of Desire. Meanwhile, the 2015 historical drama Nirvana in Fire cast 39-year-old actress Liu Mintao as the mother of a character played by 33-year-old Wang Kai.

As Taiwanese actor Wu Qilong, 49, once said to his female peers semi-jokingly during a press conference: “You may have played my younger sister in the past, then started playing my girlfriend or my wife. In a few years, you may be playing my mother.”

Globally, male actors’ careers peak around 46, while for women, the pinnacle is usually 30, according to a 2015 analysis of 6,000 actors by TIME magazine. Now, Song Dandan’s remarks have led a legion of Chinese actresses to publicly express their frustration with the industry’s rampant, sexist age discrimination.

Actresses are increasingly pigeonholed into domestic roles after middle age

After taking a break to have children in 2013 and 2016, actress Yao Chen, struggled to find work, as she said at a talk held by Tencent last year. Though Yao is one of China’s best-known stars—winning acclaim for her role in March’s family drama All Is Well, and being named as the face of the Golden Rooster and Hundred Flowers Film Festival—the 40-year-old is uneasy about her career. “This is supposed to be the mature period for an actress,” she said, “but in the market…all the stories are about young boys and girls. I’m not ready to play a mother to them yet.”

As in other fields, marriage and motherhood often derail a woman’s career. After finding phenomenal success in the TV series Empresses in the Palace, Lan Xi, 36, left showbiz for two years to raise a family, and struggled to find work afterward. “You can never really balance life and career,” actress and mother Ma Yili has said in an interview with ifeng.com. “I don’t believe anyone can handle both roles as a successful professional and a good mother at the same time.”

Remaining single or in work is no panacea to the problems of a lack of scripts for middle-aged actresses and ruthless competition for younger roles—not to mention, derision from society. When 44-year-old actress Zhou Xun played the protagonist of costume drama Ruyi’s Royal Love in the Palace—a role that spans about 40 years in the character’s life—audiences accused her of looking “clumsy” and “unnatural.”

Similarly, 40-year-old Chen Qiao’en was accused of “looking too old” for her role in Sui dynasty show Queen Dugu. “Since when has the only angle through which people view an Eastern woman been whether she looks young?” Chen sighed on Weibo, where phrases like “pretending to be evergreen (装嫩)” and “chick religion (丫头教)” are routinely used to denigrate older actresses for daring to act younger than their age.

Actress Yang Rong is often mocked for “pretending to look young”

Cosmetology High actress Yang Rong, who has been targeted by these comments online, wrote a passionate Weibo essay last year in which she confessed she was afraid to be defined as a “middle-aged actress.” This label, argued the 38-year-old, translates to “very famous, but with no roles to play”: “It’s not because I am afraid of aging…but the current industry environment makes actresses afraid of aging. Actresses in their 30s, like me, have to try very hard to maintain our image as young girls.”

Many in the industry argue that the situation is a matter of audience preference. In 2015, actress-director Zhao Wei, 43, told ifeng.com that the market is saturated with dramas “about young people crying after being dumped.” “How can such stories have any depth?” Zhao asked. “They have a market, though.”

But now echoing actresses’ complaints is a growing audience of mostly female viewers, calling for more middle-aged women to play leading roles in entertainment. Last year, a poster for an alleged TV show called The Lady (《淑女的品格》) went viral online, featuring four middle-aged actresses—47-year-old Yu Feihong, 41-year-old Chen Shu, 42-year-old Zeng Li and 41-year-old Yuan Quan—playing an elegant designer, acerbic teacher, philanthropic businesswoman, and poker-faced doctor respectively.

The show turned out to be wishful thinking, but, “I’m begging investors, screenwriters, directors, and producers to cast more women over 40,” the creator wrote on Weibo. “The poster is fake, but my wish is real.”

It’s clear that there’s an appetite for stories featuring mature, powerful women: The Lady’s hashtag acquired over 190 million views, promoted by Chen Shu and Zeng Li themselves, and new fan-made trailers and posters followed in rapid succession: “Let’s see whether the market dares to make some room for [them],” observed one popular Weibo comment.

Such was the enthusiasm, that production company Easy Entertainment declared last May they had contacted the creator of the original poster, and planned to make the TV series a reality. A year has passed, however, and fans are still waiting.

“Mid-life Crisis” is a story from our issue, “The Amusement Issue”. To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine. Alternatively, you can purchase the digital version from the iTunes Store.