One migrant worker’s journey from reproducing Van Goghs in an “art factory” to painting on the streets of Amsterdam

Dafen is a small village outside of Shenzhen. The name Shenzhen recalls economic reform, the factory of the world. But you might not realize that there is another kind of factory here—filled not with the rumble of machinery, but rather the soft strokes of paint brushes; smelling not of plastic and glue, but oil paints.

Dafen village is that place.

In 1989, Hong Kong merchant Huang Jiang arrived in Dafen. He rented a house, hired workers, and started filling orders to copy well-known Western oil paintings.

Unexpectedly, this kicked off a period of wild growth for Dafen, attracting all kinds of business around the production, sales, and export of oil paintings. Over time, the village became a global center for this industry. Oil painting sales reached 200 million RMB at their peak. Countless “Starry Nights,” “Water Lilies,” and “Mona Lisas” left Dafen village for destinations around the world.

All of those reproductions of renowned paintings were produced by migrant workers. Zhao Xiaoyong was one of them.

-1-

Destined to paint

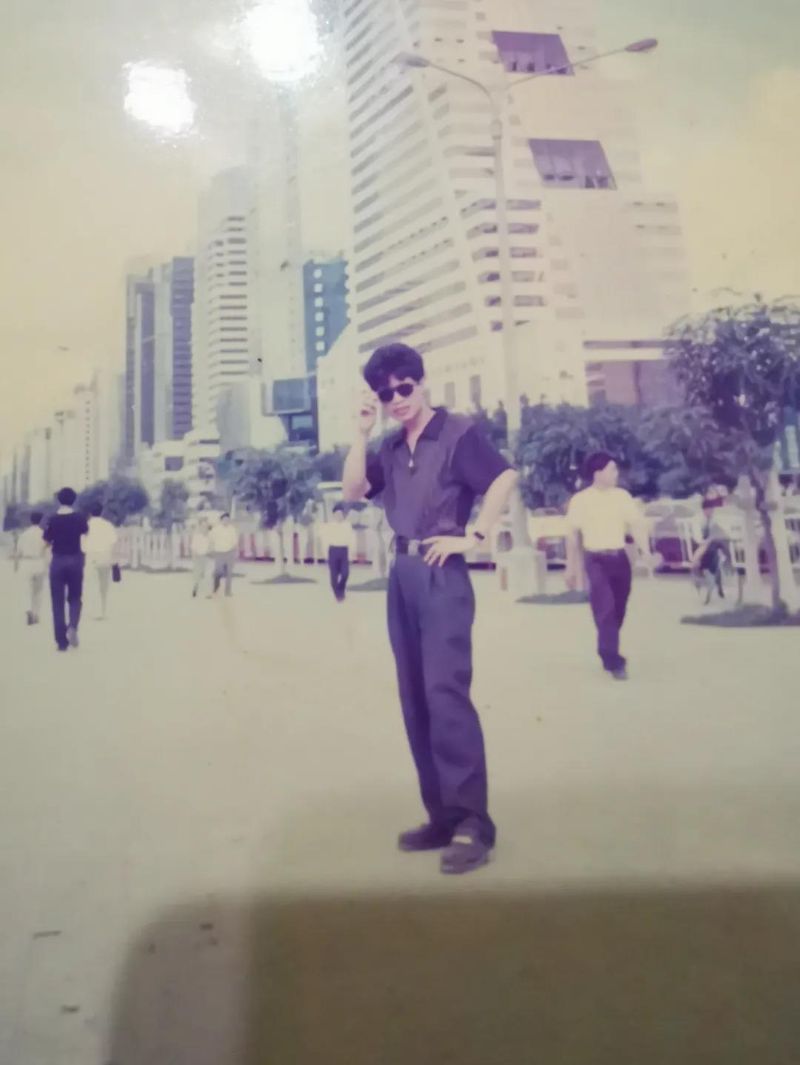

I was born in 1972 to an ordinary rural family in Shaoyang, Hunan province. I’ve loved art since I was little, but my family didn’t have the means to support my interest.

In 1989, I came to Shenzhen, joining the tide of migrant workers into cities on the coast. We rode battered bicycles, zipping around the city looking for jobs. But two months passed, and I still hadn’t found work. Sometimes we’d make it to the front of the line at the recruitment counter after a long wait, only to have the recruiter take one look at our IDs and say, “They’re from another province, we can’t take them.”

I was getting worried, so I told the recruiters, “We don’t even want a salary, just room and board.”

Later, I ended up doing construction on the waterfront in Shekou. It was hard work, and I was young—I couldn’t handle it. There were tons of mosquitoes by the ocean in Shenzhen. They were as big as bees. We would light three or four sticks of incense at night, but it was no use. The best we could do was wrap tape around our faces and feet, but even then we still couldn’t sleep.

In 1992, I went to work in a factory that made rattan baskets and crafts. My job involved painting pictures onto the products, applying color. This was the kind of work I had dreamed of.

At the time I really enjoyed painting. Off work, I would get together with fellow workers and paint, sometimes until late in the night. We’d paint celebrities like Andy Lau, Jacky Cheung, and Aaron Kwok.

The factory’s designer was a Filipino guy who took a liking to me, and took me as his apprentice. He showed me how to mix colors, how to paint. Just like that, little by little, I ended up learning quite a lot.

Maybe it was my destiny to paint.

In 1993, I switched to working in a Taiwanese factory that also made handcrafts. Since I was skilled, they had me do the most difficult parts. I worked there for four years. Even in those days, I was already taking home over 1,000 RMB a month, and the factory manager thought very highly of me.

One day, one of the factory workers from my town asked me, “You like painting. Have you done any oil painting before?”

I said I hadn’t.

His brother produced oil paintings in Dafen village, so he took me there. Back then, painting in the village hadn’t scaled up yet. There were no galleries. It was just 20 or 30 people painting in small studios.

I was moved the first time I saw the oil paintings there. They were so delicate. The people’s eyes and skin looked so vivid, so alive.

How could those paintings be so beautiful?

After we got back, I said to that other guy, “Why don’t we go paint in Dafen?”

He agreed.

We quit our jobs and came to Dafen village. After a month, the other guy didn’t want to paint anymore and went back to our old factory. I stayed on.

Could I really make a living in Dafen? Could I learn to paint well? Those were questions I didn’t consider.

I had gone there purely out of love for painting.

And having arrived, I didn’t want to go back.

-2-

My first paintings

From 1996 to 1997, I studied oil painting in Dafen village. Back then, the village was a beat-up shantytown. Even from a distance, you could smell the sewage in the gutters.

All of the painters there were rushing to fill orders, so nobody was going to hold my hand. I had to learn by trying things for myself.

In the beginning, I couldn’t sell any of my paintings. I had no income, so I had to borrow money from everyone. Until another guy from my hometown found me.

He had a lot of orders to fill, and asked me whether I would come help him with the underpainting. He also taught me a lot about color.

Out of that first batch of orders, I did about 20 paintings and received 800 or 900 RMB. That was the first money I made in Dafen—I was so happy.

With an income, I could keep buying canvases, paints, and books. I promised myself that I would master the works of Van Gogh.

I got my start with Van Gogh’s “Café Terrace at Night.” The first copy came out poorly, so I painted another, and from there I started to get a feel for it.

By the third copy, a gallery owner purchased my “Café Terrace at Night,” along with my reproductions of other Van Gogh works. Not only that, but he managed to sell them all.

I thought that since there are people out there buying my paintings, I’ve got to work even harder.

In 1998, I founded my own studio. By the start of 2000, with Dafen village becoming more and more famous, every studio in the village was receiving tons of orders. It was the norm in our studio to start painting at 2 or 3 in the afternoon and go until 3 or 4 in the morning, sometimes even painting through the night.

At night, every studio in Dafen would listen to a radio program called The Night Sky Is Not Lonesome. The program was made especially for drifters, people far from home. Our group of painters would even call into the program sometimes.

In that deep silence, the only sounds in the whole village would be the songs on the radio and the whisper of brushstrokes.

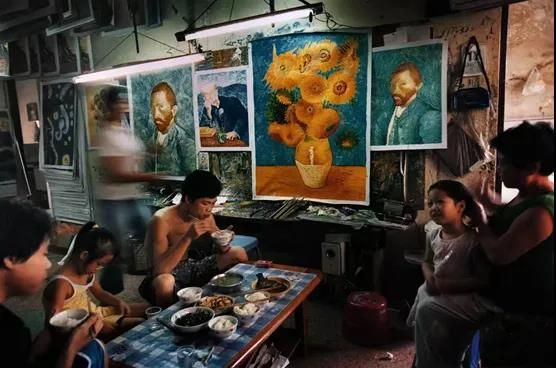

Workers eating in an art workshop in Dafen Village (China's Van Goghs)

-3-

The assembly line

One time, I happened to meet a purchaser from Hong Kong.

As soon as he came into the store, he started complimenting my paintings. He pulled 10 photos of Van Goghs out of his bag—we worked from photos when we made our reproductions—and wanted to discuss an order of 20 paintings with us.

At the time, supply couldn’t keep up with demand in the oil-painting business, and Hong Kongers made up the largest customer base in Dafen village.

I thought to myself, I’ve got to make the best of this opportunity. That month, I did a very careful job on those 20 paintings, and the customer was very pleased upon delivery. He immediately gave me another 20 photos, each one to be copied 10 times!

Since this was a big order, there was no way for one person to fill it alone, so I called on my wife and younger brother for help. I met my wife when we were working at the same factory, and she also knew a bit about painting. She was a quick learner—it took her only three months to learn how to paint “Starry Night.” She can paint it even better than I can now: She doesn’t need to look at a reference, just pick up her brush and churn one out.

So my wife painted “Starry Night,” and my brother helped me with the underpainting.

Later on, around 2001 or 2002, I received an even larger order: 5,000 copies of Van Gogh’s “Irises.” We spent a whole year copying just this one painting! One person from our studio painted the background, one person painted the flowers, and another person painted the vase.

Even though I’d already reached my limit, this rate still wasn’t fast enough to compete in Dafen village. In 2003 and 2004, the orders only kept growing. We had to finish 1,000 paintings a month. So I called up my relatives from back home and had them come help out.

During that time, seven or eight of us would squeeze into a rented room to paint. We nailed drawing boards along a few of the walls, and every day we churned out paintings. We slept and ate in that room. If we got tired, we’d just put a straw mat on the floor and fall asleep right there.

And do you know how long we worked like that?

Ten years.

We suffered through those 10 years. I turned that studio into a factory in order to feed my family, and I didn’t think about anything else. I didn’t think about what we would do in the future, or what we would do if the orders stopped coming.

-4-

A long-held dream

When the financial crisis broke out in 2008, the market for oil paintings collapsed. I got only one batch of orders that whole year. In order to survive, I converted my studio into a gallery and sold paintings.

One day, a customer came in and exclaimed, “This must be the Van Gogh Museum!”

I teased him: “And how would you know what the Van Gogh Museum is like?”

“Well, I happen to be from the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam,” he said. “If you go to Amsterdam, I’ll take you to visit the museum.”

I was astonished, but I thought he was only joking, so I didn’t take it to heart.

I also remember, back when I was renting an apartment with a friend, he suddenly called out to me one night, all excited, “Xiaoyong, Xiaoyong! Quick, come look at the TV!”

They were showing a film about Van Gogh. This was the first time I learned about his life—he was so dedicated to painting, to art. I found his story very touching.

I became obsessed with Van Gogh, buying many biographies and books of his prints. I wanted to have a deeper understanding of his paintings. But even so, printed reproductions are still different from the originals.

Ever since I started copying Van Gogh’s works in 1999, I always wanted to go see the real thing. But I also knew that this could only be a dream. Europe was too far way and too expensive. And every day, I had orders to fill.

-5-

In Amsterdam

In 2013, the father-daughter documentary makers Yu Haibo and Yu Tianqi found me. They wanted to make a film about my life. With their encouragement and support, I made a trip to Amsterdam.

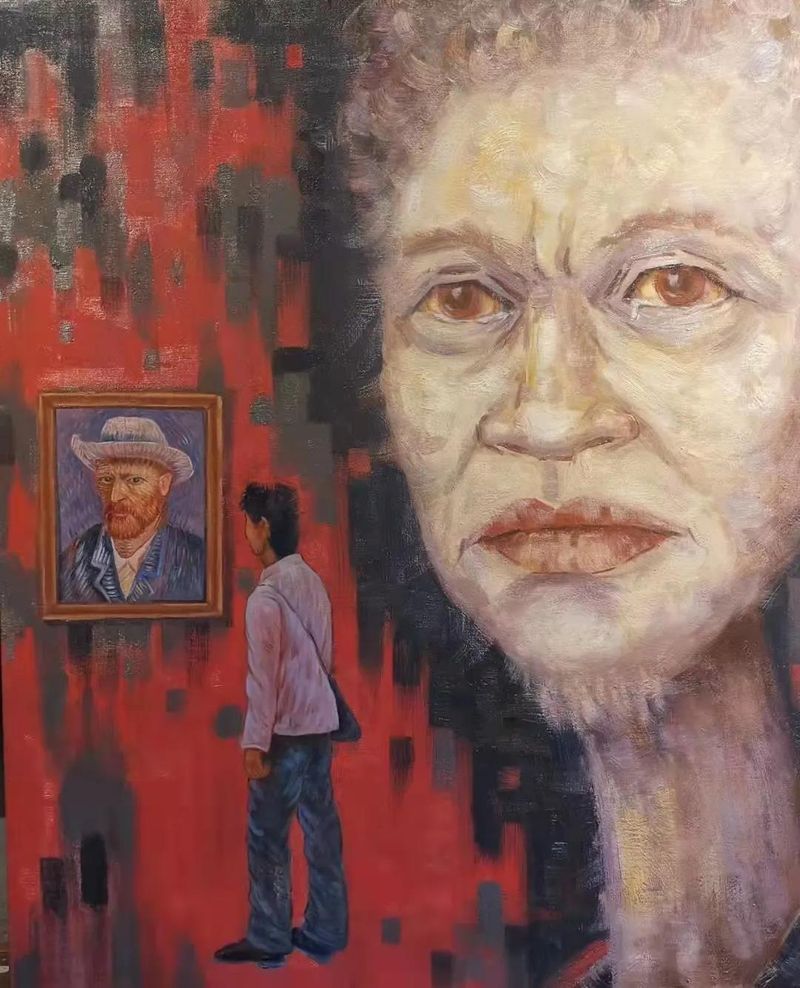

Outside the Van Gogh Museum, I was still some distance away when I spotted one of Van Gogh’s self-portraits, magnified for display. I immediately got excited, because it was one of the ones I’d painted.

It turned out that this was the gallery of the customer who had once come into my shop. But upon entering, I found that it was only a mobile souvenir shop, similar to a shipping container. It had seemed like an extraordinary thing for my paintings to be sold in Europe. But my paintings weren’t on display in a gallery, as I imagined, nor were they framed. They were simply stacked up and nailed to the wall.

That was pretty discouraging.

Later, our group went in to tour the museum. As we came through the doors, the first thing I saw was one of Van Gogh’s self-portraits. I couldn’t help but stick my face up close to look.

It wasn’t the same. It wasn’t the same as how I painted it.

All those years, I’d looked at so many prints and books. But it was only standing in front of the real work that I saw how different it was from the pictures. The books showed thick brushstrokes and vibrant colors, but the painting in the museum had delicate brushstrokes and subdued colors.

Aside from that self-portrait, the painting I looked at for the longest was “Sunflowers,” which was the Van Gogh work I’d copied the most times.

I found this painting very odd, because the four corners of the canvas had different kinds of brushstrokes. One of the corners used a No. 1 brush, but when you look at the other corners, they’re No. 3 or No. 4. I thought, when Van Gogh was painting this work, he must have been trying different things all the time.

Van Gogh was very isolated when he was painting “Sunflowers.” At the same time, his good friend Gauguin provided some moral support for him. Maybe it was to welcome Gauguin to his little room, or maybe it was to get him to stay a bit longer, Van Gogh put all of his desires for camaraderie into this painting. From the changes in the brushstrokes, you can sense that he was dedicated, yet still reserved.

-6-

Goodbye, Café Terrace

Afterward, we wandered the streets of Amsterdam. Just before dark, we happened upon the real-life location of Van Gogh’s “Café Terrace at Night.” It really was just like in the painting.

“Café Terrace at Night” was also the first Van Gogh reproduction I finished by myself.

I was in such a good mood that night, I bought two bottles of liquor in the café and got pretty drunk.

During the four days we stayed in Amsterdam, every night we would stop by that café.

Mr. Yu said to me, “Why don’t you paint something right outside the café?” I said, “OK.”

There was no easel, so I found a wine barrel to paint on. I’d never worked like this before. My knees were trembling as I sketched out the scene.

But I worked quickly, and the painting was done in half an hour. The locals around me all crowded up to look and said I painted really well. The café’s owner was also watching me the whole time. When I finished, he asked me—a bit embarrassed—if I would give him the painting, and I said yes.

He was very happy to receive the painting, and hung it by the bar. If I go back there in the future, I’ll be able to see the painting again.

That night, I stood in the same spot where Van Gogh stood, and painted what he painted.

Later, we also visited many of the places Van Gogh had been while he was alive. Our last stop was Auvers-sur-Oise, where he painted his final work, “Wheatfield with Crows.” Less than 100 meters from that wheatfield was the final resting place of Van Gogh and his younger brother.

Most of the graves in this cemetery were very fancy, with ornate carvings. But Van Gogh and his brother’s graves were very plain and covered in ivy.

It was raining that day, and we picked wildflowers as we went. A young man lit a few cigarettes and set them in front of Van Gogh’s tombstone. We set our flowers down next to them.

On our way back from the cemetery, as we passed the wheatfield, the sky was blanketed with dark clouds. We couldn’t help but yell Van Gogh’s name to the skies.

As we yelled and yelled, a flock of crows rose up from the field.

-7-

Van Gogh is watching me paint

After we got back from the wheatfield, I couldn’t sleep that whole night.

I’d painted Van Gogh’s works for 20 years, but no matter how well I painted, what was the use? I would sell one and have to paint another all over again. And those works would always be someone else’s, not my own.

Before going to the Netherlands, I was partway through a copy of “The Potato Eaters.” When I got back to China, the first thing I did was finish this painting. Then I painted all of Van Gogh’s works one more time. Later, all of those paintings got sold. The only one I kept was that copy of “The Potato Eaters.”

Then I started trying to paint some of my own works.

My wife had been with me for so many years, and we’d painted for so long, but she didn’t have a painting of herself. The first original painting I did was of my wife.

When I finished the painting and showed her, she was very pleased. Later on, someone wanted to buy it, but she refused to sell.

In recent years, I’ve painted many series: ones about my hometown, about Van Gogh, and about myself.

Thinking back to the first half of my life, it all feels like a dream. It’s as if from the moment I decided to go to the Netherlands, I entered a long dream.

In my dream, I met the real Van Gogh. He stood right next to me, watching me paint.

___

This story is published as part of TWOC’s collaboration with Story FM, a renowned storytelling podcast in China. It has been translated from Chinese by TWOC and edited for clarity. The original can be listened to on Story FM’s channel on Himalaya and Apple Podcasts (in Chinese only).