As brick-and-mortar KTVs struggle, KTV apps and mini-booths are heralding changes in the industry

“Most users are purely interested in singing, like me, but some may come to watch good-looking men or women record the singing process,” Han Xiaona, a postgraduate in Beijing, told TWOC, as she played of her best-recorded songs via Chang Ba (唱吧, literally “Singing Bar” or “Sing!”), an app which boasts being “the most popular Karaoke on mobile.”

Chang Ba is just one of many ways in which the KTV industry is currently transforming. It topped the list of free apps with the most downloads on the Chinese App Store only five days after its launch in 2014, attracting over one million users within 10 days, and was installed on 100 million terminals within 480 days.

Tencent launched its own version, Quanmin Kge (全民K歌, or WeSing for the English version) in 2014. By mid 2016, it had taken the top spot for singing apps, with Chang Ba falling to second, according to the China Internet Weekly.

KTV has long been a boom industry in China. Apps like Chang Ba and WeSing are taking it a step further by bringing social media into the mix.

“Chang Ba is more than free, mobile KTV,” Han said. The app can “beautify” users’ voices to make them sound better or funnier, which certainly strengthens their interest in singing. “It’s also a means of communication between me and others who listen to my songs. After my mom and other family members shared my songs on their QQ and WeChat account, I’ve even gained some ‘fame’ in my hometown.”

In addition, fans can interact with their favorite singers such as Han Hong (韩红), as more celebrities register to join.

However, unlike the live-streaming app Kuaishou, where users often seek attention in “innovative” ways, Chang Ba offers no material motives. It charges for virtual presents, but they cannot be cashed. Chang Ba has also worked with popular performance shows such as Hunan Satellite TV’s Come Sing with Me to promote its celebrity users. Users whose songs are most liked on the app can even be invited to sing with popular singers on the show.

In the real world, though, the last few years has seen the traditional KTV business shrink, due to rising costs and messy competition. Party World, a leading KTV chain in China, closed 14 of its 18 outlets in Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou. Chen Hua, CEO of Chang Ba, told tech.qq.com that he still saw many opportunities in this sector. “Though there are many KTV chains in China, many are in small scale [with limited competitiveness]…and since their VOD systems and operation are separated, much could be done to improve customer experience.”

Following other startups which made the switch from online to offline, Chang Ba has tried to dip its feet in the KTV sector. In May 2014, Chang Ba entered a strategic partnership with a Beijing-based KTV chain brand to launch physical Changba Mysong KTV stores, a new “Internet + KTV” platform featuring remote and on-site interaction combined with social networks, entertainment and media. Since then, nearly 100 such stores have been established in over 30 cities of 20 provinces and municipalities, which will be expanded to 2,000 nationwide with franchising deals. There are also plans afoot for self-service KTVs that don’t require human staff.

This February, Chang Ba extended its business to miniature KTV booths, investing in Guangzhou-based Aimyunion Technology Co., Ltd., which specializes in producing musical equipment like the mini KTV. Their collaborated miniK Changba (formerly known as miniK, the booth is a self-service KTV with an area of about 2 square meters, 2 barstools and a full set of karaoke equipment), is mainly installed in shopping malls, cinemas, and other populated areas. Approximately 20,000 booths by 10 brands have been set up in China since last year, including the M-bar collaboration between WeSing and the Xiamen-based U-sing.

A miniK booth (meda.cc)

Still, it was perhaps inevitable, given the longstanding connotations of KTV in China, that mini booths would attract the wrong kind of attention. Growth in this area came to a halt in July when the Ministry of Culture issued a notice that dictated how the sector would develop “healthily,” citing concerns about hygiene and copyright infringement.

As always though, only time will tell whether the mini KTV booths can take off in China.

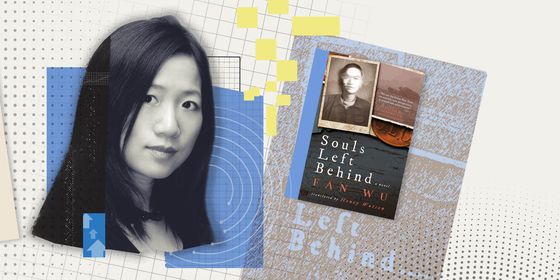

Cover image from Sohu