China’s emperors were no strangers to the curse of bad data—and built their own secret system to avoid it

What would the emperors of the Qing dynasty have thought about a world in which leaders communicate strategy and policy via Twitter? It’s unlikely the Qing would have been too keen on mass—never mind “social”—media, but they were innovators in the field of official communications. They ran a system which relied on big data long before there were microprocessors and fiber optics to transmit such information. Keeping tabs on a bureaucracy spanning an empire was a full-time job and required progressive thinking in the fields of communication and information management.

Under the system of court correspondence inherited from their Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644) predecessors, information and communications flowed up via official channels, passing through the relevant ministries, where a bevy of staff and bureaucrats read each dispatch before forwarding it to the appropriate minister for review. Only then would the information, along with a policy recommendation and drafted response, make its way to the emperor. It was a cumbersome—yet very open—system.

Towards the end of his long reign in the 18th century, the Kangxi (康熙) Emperor grew concerned about how the quality of the information inevitably degraded by the time it reached his desk. With so many eyes reading each document, and so many hands crafting the official reply, it was almost impossible for the emperor to know what was happening, even in his own household. In particular, he was worried about his son, Yinreng (胤礽), the crown prince.

Disturbing whispers were swirling around the 178-acre palace about Yinreng’s instability, and predilection for underage boys and girls. Were they true? The Kangxi Emperor had in the past employed a scheme of having officials slip a private note into official greetings sent to the throne. This was originally used as a way for the emperor to check up on the accuracy of harvest reports and tax figures—routine matters to be sure, but also information that was readily exaggerated or falsified.

The Office of Military Finance, located in the Forbidden City (VCG)

The emperor revived this system, asking certain officials to send information—for imperial eyes only—on the misdeeds of his chosen heir. No longer concerned about being reported by others, these officials sent in a flurry of memorials which painted a grim picture of a young prince out of control. With a heavy heart, the Kangxi Emperor renounced the heir apparent on grounds of immorality, sexual impropriety, and treason.

These secret missives would evolve into a system of confidential palace memorials (密折) which, in the mid-to-late Qing era, became one of the leading forms of official communication with the throne. These memorials could be submitted only by a carefully chosen group of high mandarins, and each was to be written by the sender personally; not even their private secretaries could read what was in them. The document was then entrusted to a private courier—sometimes sent locked in a special box gifted by the emperor for the purpose—and taken to the capital, where the courier would bypass the ministries and bureaucrats of the Outer Court and deliver the message directly to an office set aside in the inner sanctum of the Forbidden City. There, it would await the emperor’s—and only the emperor’s—perusal and response.

The Kangxi Emperor is credited with devising this system, but it was one of his sons who would perfect it.

The decision to disbar Yinreng set off a brief struggle among Kangxi’s other 23 sons following his death in 1722, and it was the fourth son who emerged from the fray to become the Yongzheng (雍正) Emperor. His reign lasted only 13 years, but he was an energetic, if paranoid, ruler. It would be the Yongzheng Emperor who transformed the system of memorials from an informal mechanism to aid in the gathering of intelligence to a tool for increasing his power, and that of the Inner Court, at the expense of the wider imperial bureaucracy.

The Kangxi Emperor had done much to expand the boundaries of the Qing empire; the Yongzheng Emperor would need to work just as hard to whip an increasingly recalcitrant and independent bureaucracy into shape. He increased the number of officials who could use the system, formalizing previously ad hoc channels of information into a powerful implement of imperial power.

In the last 13 years of the Kangxi Emperor’s reign, the throne had received about 2,500 confidential letters. In the 13-year span of the Yongzheng era, officials sent over 25,000 memorials, a ten-fold increase.

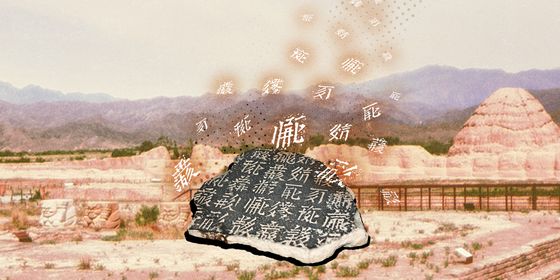

A portrait of the Kangxi Emperor (VCG)

Any other emperor would have been overwhelmed, but the Yongzheng Emperor prided himself on an iron work ethic, bragging that he read and responded to 60 memorials each day. He became his own chief executive, using the memorial system to avoid dealing with the partisan bickering and pedantic reminders about rules and regulations coming from the outer court and the ministries. It also gave him the opportunity to play a more significant role in military matters, knowing that he had a secure channel of communication with his generals.

Finally, it allowed the emperor flexibility in funding his wars and schemes. In his responses, the Yongzheng Emperor frequently suggested expedient, and sometimes elegant, solutions to problems, even if those solutions would likely not have met with the approval of pernickety ministries concerned with procedure and policy.

But even the most energetic monarch sometimes needs an assist. To keep up with the flow of information, and to assist him in formulating replies, the Yongzheng Emperor turned to another innovation: The Office of Military Finance (军机处), what foreigners in the 19th century would call the Grand Council. This “Kitchen Cabinet” initially consisted of three men: one of the emperor’s younger brothers, and two very senior and trustworthy Chinese officials. The Office had been created to handle logistics and the task of funding military conquest, but now it became a clearinghouse for the emperor’s secret correspondence, as well as an informal “leading group” for the emperor to plot and plan, unhindered by the civil service.

The Yongzheng Emperor relied on both the confidential palace memorials and the Grand Council to uncover tax dodges, root out corruption and terrorize lazy or incompetent officials. High officials were encouraged by the emperor’s responses—written in vermilion ink—to give him as much dirt as possible. It also gave the emperor a forum for expressing himself, without worrying about judgmental bureaucrats.

In her book, Monarchs and Ministers: The Grand Council in Mid-Ch’ing China, 1723 –1820, historian Beatrice Bartlett quotes one memorial in which the Yongzheng Emperor made known his feelings about an incompetent member of his staff: “Ho Ching-wen is a good-hearted, hard-working old hand. I think he’s very good. But he’s a bit coarse. By nature, he is just like Chao Hsiang-ku’ei, except that Chao Hsiang-ku’ei is intelligent.” To another bureaucrat, the emperor was even more blunt: “You are one of those mediocre provincial officials appointed on a trial basis because I couldn’t find anyone better.”

Like all communication innovations, what started as a disruptive new form of information gathering and dissemination eventually became routinized and bureaucratized. The Yongzheng Emperor’s son and successor, the Qianlong (乾隆) Emperor, would rely on confidential memorials to plan expansionist crusades, as well as intervene directly in particularly troubling outbreaks of insurrection, or investigations of state subversion.

But by the 19th century, and especially during the unofficial reign of the Empress Dowager Cixi (慈禧), when emperors became something of an afterthought, confidential memorials became just another form of imperial communication. In the absence of strong central leadership, the Office of Military Finance emerged from the shadows to take on an executive function, but it also increasingly became just another layer of bureaucracy, perched precariously at the apex of an already top-heavy government structure.

Ask any chief executive, and they will tell you that one of the hardest parts of leading an organization is getting quality information on which to make decisions. The Qing emperors were no different, and the system of confidential memorials they created became one of the most valuable pillars of their long rule over China. While the effectiveness of the system declined—along with imperial leadership—toward the end of the Qing era, it was one of many important innovations the Manchus made in building and maintaining their improbable empire.

Today’s technology makes the Qing system of palace memorials seem quaint by comparison, but the goals are the same: How to collect and store data to make the country run as efficiently as possible.

Court Confidential is a story from our issue, “Cloud Country.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.