On World Consumer Day, we look at the history and controversial health claims of China’s milk-based drinks

Forget the slowing economy. Fake news is “the biggest source of harm” to his business, according to beverage tycoon Song Qinghou.

These comments made on the occasion of the Two Sessions by septuagenarian CEO of drinks conglomerate Wahaha echoes comments he made in 2015, in response to a spat of rumors that his products have caused, among other horrors, leukemia, while its Nutri-Express drink leaves a residue thick enough to be made into condoms. Wahaha’s line of bottled probiotic “milkshakes” has seen its annual sales drop from 400 million cases to 150 million since 2014.

Nutri-Express is just one of many “formulated milk beverages” (FMBs) in the Chinese consumer market. Defined as beverages that use milk as a base ingredient supplemented with additives including flavoring agents, nutrients, and bacterial cultures, the drinks occupy a formidable slice of the Asian beverage market—not too dissimilar to the yogurt or flavored milk shakes found in Western supermarkets.

As a result, foreign dairy producers, yogurt companies and drinks makers, along with their assorted marketing research firms, have long being eyeing whether the popularity of FMBs in China creates a lucrative market for them. According to recent reports in click-bait dairy media like Dairyreporter.com and Dairyfoods.com, “Chinese dairies are jumping on the probiotic bandwagon,” creating opportunity for foreign brands “to develop a premium segment in the single-serve yogurt category” in mainland cities.

Amateurs.

Researchers may have reported that dairy consumption is going up overall in the Chinese market along with rising urban incomes, and FMBs in particular are focusing more and more on health-oriented branding and marketing.

But commercially packaged probiotic drinks have been a thing in China since Wahaha was founded in 1987 and began to sell its Lilliputian six-pack “乳酸菌饮品” drinks (branded with the literal “Lactic Acid Bacteria Drink” in English), imbuing the childhood memories of the post-80s and early post-90s generation with their distinctive salmon hue.

Wahaha Lactic Acid Bacteria Drink [Feiniu]

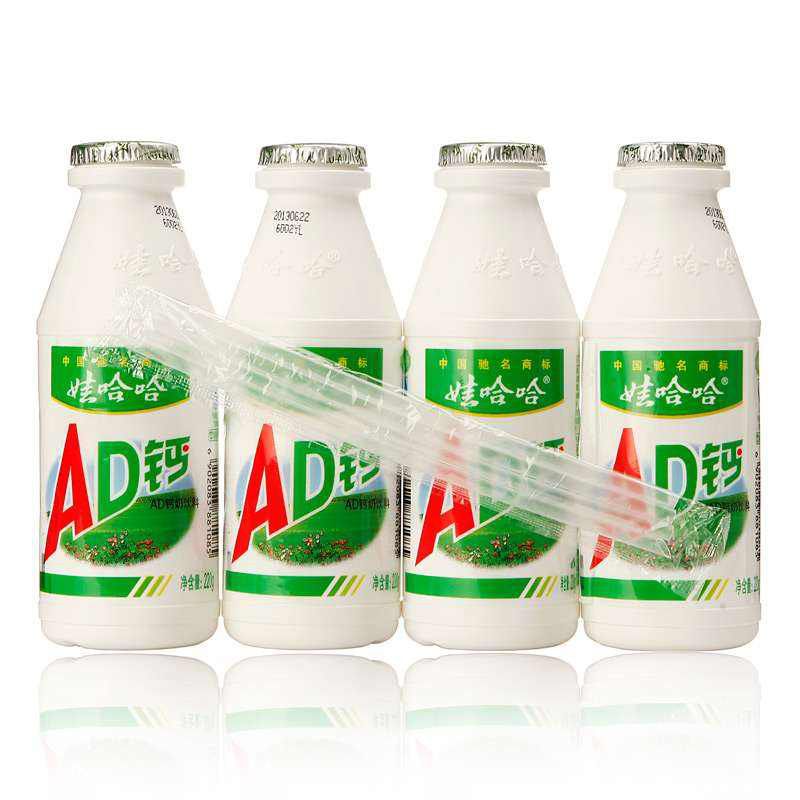

Wahaha AD Calcium Drink [Hrydg.com]

Yili milk drink with fruit pieces [Yhd.com]

Prior to this, Japanese company Yakult had been making available essentially the same drink, down to the color, most elsewhere in Asia since 1935, though Yakult only came to China in 2001. In 1997, Wahaha launched AD Calcium Milk, a drinkable yogurt line that became nostalgic fodder for the next generation, foreshadowing the market boom for new FMB products and formulas over the next decade: Yili’s drink containing fruit pieces (2008), oat-flavored milk and Nutri-Express (2004) are some of the most creative examples. In 2015, Pepsi announced it was launching its own oat-flavored FWB for the Chinese market.

Netizens who have spoken out support of Song’s statement this week cited their lifelong consumption of favorites such as 乳酸菌 and AD Calcium since childhood as proof of the brand’s “time-honored” status, but FWBs have had a longer history in China than even Wahaha.

Yogurt made from yak milk was famously mentioned in records of Princess Wencheng’s journey to Tibet during the Tang Dynasty, and the brewing of kombucha (茶菌, “tea bacteria”), which contains lactic acid bacterial (lactobacillus) among other cultures, is also believed to have started in this period.

The production of kumis, fermented mare’s milk made from a liquid base of a similar consistency to today’s lactic-acid bacterial drinks, has also been practiced among ethnic minorities north of China for millennia and mentioned as a delicacy numerous times in the imperial records of Han and Tang dynasties. It was also produced in a few places in China during the Mongol-ruled Yuan Dynasty, when it had an important ceremonial role, a variety of health benefits were attributed to it—for instance, by improving blood circulation and promoting digestive health.

The popularity of FMBs in China (and the rest of East Asia by extension) is also related to biology: it’s estimated that around 60 percent of the Chinese population has some level of lactose intolerance, making formulated milk products and especially those formulated with lactobacilius historically and currently easier to digest.

There have even been studies as to whether consuming lactobacillus improves lactose tolerance in adults. The tremendous growth of dairy consumption has actually seen the largest increase in consumption of “regular” (fresh) milk, which in addition to lactose intolerance, also faces the problem of a shorter shelf life, especially in parts of China not equipped to provide the proper cooling chain for transporting and storing fresh milk products.

But what about the health benefits? Health marketing is a third factor contributing to the current popularity of FWBs and lactobacillus drinks, and we’d be remiss on this World Consumer Day if we didn’t take a closer look at these claims.

While there is no proof that Wahaha products cause leukemia, their FWBs and Nutri-Express in particular have been criticized in the past for containing far fewer nutritional benefits than they claim. The base ingredient of most lactobacillus-containing FWBs today are water mixed with powdered milk rather than real milk proteins, unlike the semi-solid yogurts that come in a container or regular milk.

They also contain sugar, flavoring, and various other additives whose benefits and side effects are unclear, though all within official guidelines. And this problem is not restricted to the Chinese market or to FWBs: witness the trouble that Danone or VitaminWater got into with Western health authorities over spurious health claims about their products. It seems like the notion of invisible micro-organisms working to improve our diet and digestion sounds like the modern equivalent of a magical elixir to health-conscious people all over the world. Compared to developed countries, though, Chinese law does not have the most stringent guidelines or clearly enforced penalties for making unsupported nutritional claims in food products (links in Chinese). So while the problem is not specific to China, the lack of a proper solution unfortunately is. Got milk, anyone?