The dos and don’ts of PR crisis-management in China

China’s beleaguered food-safety record breeds paranoid consumers, who will jump ship from any beloved food brand at a whiff of a scandal. When popular hotpot chain Haidilao was exposed by the Legal Mirror in late August for hygiene problems—rats in the kitchen, dustpans washed in the dish-washing sink—at two of its Beijing locations, social media bubbled over with customer complaints.

Within hours, though, online emotions had simmered down: Haidilao had done something few wrongdoing businesses manage properly, and apologized. “We are extremely sorry for the problems that were exposed and would like to express our sincere apology to the customers,” Haidilao’s Sina Weibo stated. The company then issued a second statement, offering specific solutions and naming those who would carry them out. To top things off, staff at the two offending branches were reportedly reassured that the board of directors would be taking responsibility.

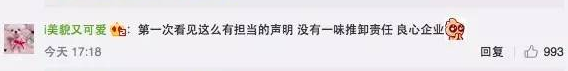

It’s the first time I’ve seen such a responsible statement, without shifting the blame; what a conscientious enterprise.

Protecting the staff, admitting fault, and correcting behavior—the statement is not bad. Looking forward to improvements, after all, [Haidilao’s] services are indeed good.

Here’s some of the best (and worst) managed PR crisis in the Chinese corporate world in recent years.

Muji’s model performance

Before there was Haidilao, Japanese retailer Muji was the poster child of PR turnaround in the eyes of the Chinese public. In 2017, CCTV’s “315 Gala,” an annual extravaganza of industry exposés in honor of World Consumer Rights Day, reported that some Muji food products were relabeled to hide the fact that they were produced in regions affected by the Fukushima nuclear accident (foods from these regions are banned for importation in China). Within 24 hours, Muji responded on both Weibo and WeChat that the offending product labels referred to their company headquarters, rather than production area.

Almost immediately, the internet mob began to rally around Muji and instead put blame on CCTV for bad reporting.

Jiaduobao’s passive-aggressive crying

Muji was fortunate, in that the truth was able to quickly set them free. Guilty parties might look for guidance instead from the Jiaduobao Group (JDB), the Hong Kong-based beverage giant.

In January 2013, JDB lost a lawsuit against Guangzhou Pharmaceutical Holding Ltd (GPH), and was ordered compensate them for false advertising to the tune of 10.81 million RMB.

The suit brought to a conclusion an 18-year, extremely convoluted tussle between JDB and GPH over the rights to use the Wong Lo Kat brand for their respective herbal tea beverages—you might know the brand as that medicinal-tasting drink in a red can. The background is relatively well-known: Following a saga of bribery, corruption, and expired contracts, JDB had to stop using the brand, announcing the change via a series of ads that declared “”Wong Lo Kat has been renamed Jiaduobao” and “the nation’s leading red tin herbal tea has been renamed Jiaduobao.”

GPH then sued JDB again, alleging the ads were inaccurate because they were the real heirs to the Wong recipe.

To this date, the Chinese public remains confused about which company is which. It was JDB that lost the lawsuit, and responded, rather bizarrely, by publishing four pictures on their Weibo account, featuring a big, passive-aggressive “Sorry!” over pictures of crying kids.

(L-R) “Sorry! We’re so dumb, that we spent 17 years making the Chinese herbal tea brand comparable to Coca Cola”; “Sorry! We were born from the grassroots and bear the genes of independent business”; “Sorry! We’re so useless that we’re only good at selling tea, but terrible at lawsuits”; “Sorry! We are so selfish that we were simply the leading seller for six years in a row, but didn’t help our ‘partners’ to build factories, complete channels and grow fast”

Since practically no one could untangle the legal aspects of the disputes, JDB figured that an emotional appeal to a classic David-and-Goliath-style narrative would win the public sympathy. They were right; never mind that JDB was actually found guilty of false advertising, the public saw them as the victims.

Gao Xiaosong’s greatest hit

There are some wrongdoings that can’t be glossed over with an ad campaign—wrongdoings that put private individuals in court, for example. But it so happens the Chinese legal system also has a built-in apology function in which defendants are expected to express remorse for their action, express their faith in the court’s verdict, and thank the court for a fair trial.

In 2011, the singer, music producer, and director Gao Xiaosong Gao was jailed for six months and fined 4,000 RMB after he crashed his car while drunk and caused a four-vehicle pile-up. Gao admitted fault and made a several minutes-long statement to the judge full of self-criticism, gratitude for his fair trial, self-criticism, expressions of lessons learned, and did we mention self-criticism?

“I’ve nothing to defend myself only regret,” stated Gao. “I always thought alcohol could bring me freedom, but it never occurred to me that drunk driving will violate others’ freedom…[The accident] was a result of my arrogance and ignorance. I’ll be a citizen who obeys the laws from now on.” He also expressed his “faith in laws” and “thanked” the media and the public “for the education.” Later, he apologized again on Weibo.

Gao is currently one of the most beloved entertainment personalities in a nation where the government monitors celebrities’ public behavior almost as closely as the public.

Lijiang’s Weibo misadventure

After the above success stories, the spectacular PR failure of a Yunnan tourism hub serves as a cautionary tale.

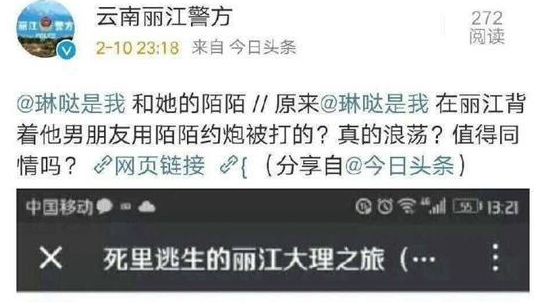

In January, a female tourist complained that she was beaten by a dozen men while eating at a restaurant in Lijiang, Yunnan province. In response, netizens piled on the local police and tourism departments for failing to maintain security at this top-rated destination.

Then on February 10, the following response appeared on the Lijiang Police Department’s Weibo account: “It turns out that [the victim] was beaten when hooking up with others via Momo [a social networking software] in Lijiang behind her boyfriend’s back. What a slut. Does she deserve sympathy?”

Yikes.

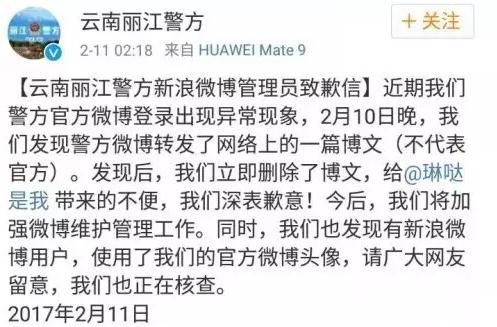

After being torched by irate netizens, the police followed up claiming their account had been “abnormally logged in” the previous day and apologized for criticizing the victim (it’s a step up from blaming “temporary workers,” at least).

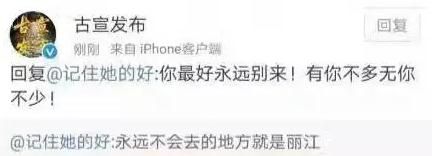

Then, on February 25, Lijiang Old Town District Publicity Department returned to the fray. After a user commented “I will never go to Lijiang” in reference to the earlier incident, they responded: “You’d better never come to Lijiang! It’s no loss to us!”

In fact, it’s no loss to either side—once a beautiful historic village, Lijiang is now glutted with domestic tourists and effectively ruined, having helped pioneer the identikit-Old-Town-redevelopment mania. In fact, the only thing Lijiang is remarkable for now is its openly hostile policing.

Cover image from flipermag.com and haidilao.com