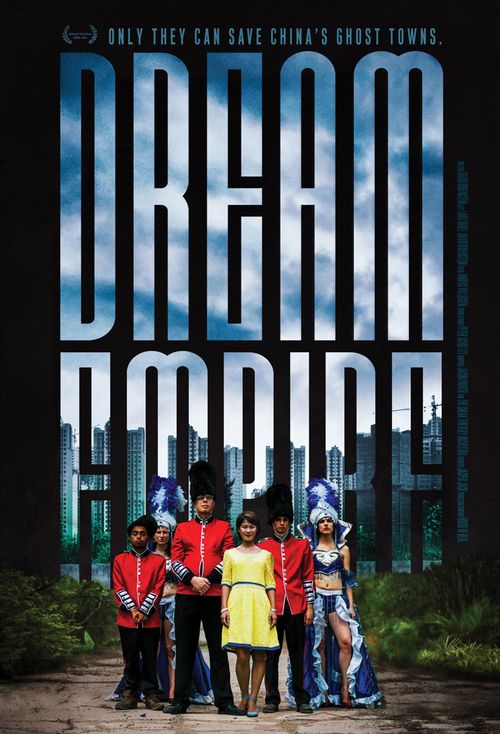

A gripping exposé of the “rent-a-white-guy” industry

It’s November 2012 and President Xi Jinping is proposing his vision for a “Chinese Dream” based on national rejuvenation and individual prosperity. One of those paying close attention is Yana, a bright and ambitious woman who we meet talking of “fresh ideas” for the “stale, behind-the-times” business environment in Chongqing.

Yana’s special plan? Recruit foreigners to act as front men and women (or “performers” as her firm’s advert states) for remote developments that could use an extra dose of cosmopolitanism and “class.” Some people, including director David Borenstein, may deem her rent-a-white-guy agency “brilliant marketing,” others as slightly sleazy fraud. Perhaps it’s simply an acceptable part of doing business in China. Any way you cut it, there’s plenty to cringe at in Dream Empire, from hapless foreigners phoning in performances for quick cash, to Yana introducing an African band as “primitive drumming and dancing.”

But Borenstein’s illuminating documentary, clocking in at just over an hour, delves beyond the tragi-comedic value of watching expats offer a Caucasian face to the biggest building boom in Chinese history, and soon becomes a character study in ambition and the seeds it sows. Yana, a Xinjiang migrant who comes to Chongqing with little more than dreams and pluck, proves an engaging subject who opens up as the film progresses; Borenstein, who arrives with a grant to study urbanization, then ends up drifting into Yana’s orbit via a series of foreigner gigs, is a faithful confidante to her growing concerns.

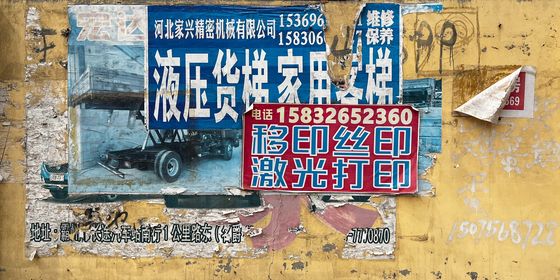

And those concerns are real. We learn how the urge to “internationalize” a city or business as a measure of economic development breeds the white-face industry, putting these lost souls near the heart of China’s future prosperity. Real estate makes up 7.8 percent of China’s GDP, according to state media, or around 15 percent if you believe overseas experts; its size is a crisis in the making, even before you add the artifice.

It’s also a ruthless business, in which everyone, from developer to buyer, ends up a commodity (black people, one client is told, “grab attention” but are also “really cheap” at about 140 USD apiece; the client wonders if hiring Indians is cheaper still). The pace is furious, solutions temporary. As cities become saturated with construction, new ones are built further to the periphery, 10 hours’ drive from Chongqing, all offering “the dream house, the perfect life.”

Yet results come quickly—almost too quickly. By 2013, a self-contained, privatized urban community stands on what, only four years ago, was farmland. There are roads, utilities, a water-purification plant, and of course, a shopping center, Sea City, whose centerpiece is a vast aquarium purporting to be the largest in the world.

One can’t help feel equal parts impressed and apprehensive: What is the world’s largest aquarium doing, a thousand miles inland in this obscure corner of Chongqing? As Borenstein observes, performance and reality has blurred beyond distinction, and this rocket ride to the top of a real-estate empire has acquired a sickening sense of gravity. The fallout may appear inevitable, and interchangeable with any number of similar implosions around China, but the impression of sympathetic Yana and her journey linger long after the dream has dispersed.

The film follows Yana as she attempts to build her rent-a-foreigner business so she can buy a house for her parents. As she gradually realizes that the entire real estate industry is built on lies, she begins to struggle with the role she is playing in the industry and the price she has paid.

Jimmy: I think it’s good for you to sell your share to me. I’m local, after all. I talk to a lot of people. I can handle clients who try to cheat me. I can instantly tell if they want to work with us.

Nǐ bǎ gǔfèn mài gěi wǒ, wǒ juédé shì jiàn hǎoshì. Bìjìng wǒ shì chóngqìng rén, wǒ gēn hěnduō rén jiāotán. Yǒuxiē hūyou rén de shì er, wǒ huì kòngzhì yì xiē. Tā shì zhēn de jiǎ de wǒ yīyǎn jiù kàn dé chūlái.

你把股份卖给我,我觉得是件好事。毕竟我是重庆人,我跟很多人交谈。有些忽悠人的事儿,我会控制一些。他是真的假的我一眼就看得出来。

Yana: That’s not a problem. But why do people have to succeed?

Zhège wǒ bù dānxīn. Wèishéme rén yīdìng yào chénggōng ne?

这个我不担心。为什么人一定要成功呢?

Yana: I’ve been reading, “The Rich and the Poor.” Why do I have to be rich?

Wǒ zuìjìn zài kàn 《Qióngrén hé Fùrén》 wǒ wèishéme yào chéngwéi yīgè fù rén?

我最近在看《穷人和富人》 我为什么要成为一个富人?

Dream Empire is a story from our issue, “Beyond Go.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.