‘Pretty’ beggar sparks debate over evolving ‘industry’

The traditional image of a beggar is usually someone down on their luck—probably dressed in rags, their face smudged with dirt, sitting on the street, holding a bowl, often with a pathetic message to stir hearts to pity.

But in recent years, the “begging industry” has evolved. Today, it’s no surprise to see a beggar with a QR (quick response) code, asking motorists and passersby to scan and donate. Many question why a person owning a cellphone needs to beg, but the practice has become increasingly common.

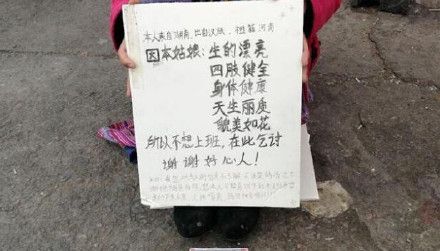

Now one beggar in Lijiang, Yunan province, has decided to save people the trouble of guessing, by explaining exactly why she was on the streets—she was too hot to work.

The woman, who looks to be in her 30s, has a sign, reading: “I come from Hunan, from the Han ethnic group. My ancestral home is in Henan. I am born to be pretty, able-bodied, physically healthy, and beautiful like a flower [editor’s note: yes, she emphasizes her good looks twice], so I don’t want to work, and come to beg here. Thanking all the kind-hearted people!”

(Images from Weibo)

Predictably, people were shocked by this rather creative explanation. Some criticized her laziness and apparent lack of self-knowledge, while others say the pretty beggar is, at least, more upfront and honest than those who make up a false, tragic story to cheat others.

Certainly, she is not the first beggar to surprise netizens. One QR code beggar in Jinan turned out to be mentally ill—his family had printed out the code to help him—but digital marketing firms warn that some beggars are “actually being paid by local businesses and startups to…entice passersby to scan them.” The data is then harvested, sold, and used to bombard innocent scanners with spam.

Other oddities include foreign beggars: In 2015, “Victor from Poland” was spotted selling his sob story at a railway station in Guangzhou, claim to have been there three days. The broke backpacker was apparently subsidizing his travel around Asia by pleading for handouts, but tolerant railway staff told reporters Victor had been there for a month, and was essentially a lazy nuisance. In a similar scam that year, an American man called Miguel or Eric bothered commuters on the Shenzhen subway with his panhandling patter, prompting allegations of pizza theft and sexual assault.

The most infamous cases, such as so-called millionaire beggars, fake beggars, healthy beggars with false injuries, and the long-running problem with beggar gangs, often employing children, has prompted most to think twice before dispensing their renminbi into the begging bowl. Others, though, are so exceptional as to become, however briefly, famous and admired, such as the “online celebrity of Lijiang.” Time will tell whether the pretty beggar is who she claims to be —a lazy woman with above-average features—or something else, like a startup entrepreneur promoting her new clothing range. But it looks like China’s beggars, like its businessmen, will never stop thinking up new ways to raise cash.