Can China’s medal factories survive the market economy?

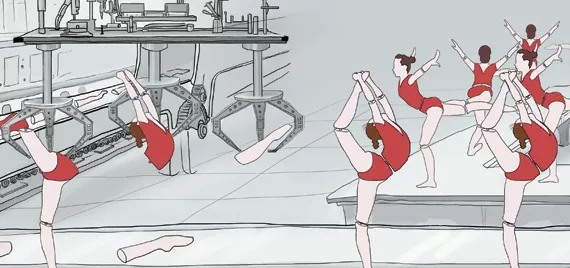

Famed around the world for efficiency and brutality, inside the Li Xiaoshuang Gymnastic School children prepare, train and push themselves to new feats of corporeal impossibility, a symbol of a nation with an insatiable hunger for international sporting supremacy. This is the catalyst for Olympic success, the grinding wheels of a national obsession, children leading the charge to a patriotic domination of the world of sport…

“I think you’ve misunderstood us,” says Yang Rui, principal of the school, confused at this outdated mindset. “We are not really into competitive sports. We are more like a kindergarten.” Though the London Games are long over, schools like this continue to train athletes for their next chance at Olympic glory, but the world is changing and China along with it. For years, practices here have been criticized for their cruelty and for good reason, but no one really complains as long as China keeps bringing home the gold. As such, little seems to have changed on the surface. But the world outside those walls has been irreversibly altered.

“The parents entrust their children to us because they want their kids to become braver, stronger, and more independent. Nowadays, most of the kids are the only child in the family, and —unless the kids choose to—the parents do not want their children to go through the kind of pain it takes to be a champion,” Yang says. “No, most of our children are not here for gold medals.” As lifestyles improve, fewer parents want to sacrifice their children to the hope of sporting glory; no one is really sure if these gold medal factories will be able to withstand the market economy’s foray into professional sports.

These athletes in Nanjing – the youngest only three- train year round and all day long with little hope of professional success

The school, located in Xiantao City, Hubei Province, trains kids from four to eight, the most crucial years in deciding whether or not a child will become an excellent gymnast. The child-gymnast schools have one of the worst reputations for abuse and cruelty, with some iconic images floating around the media of children being pushed to the breaking point. This particular school included star gymnasts like Li Xiaoshuang (李小双) and Yang Wei (杨伟). The former defined the 1990s gymnastics scene and the latter restored glory to Chinese gymnastics in the 2008 Olympics. The city was even honored by the General Administration of Sports as the “Hometown of Chinese Gymnastics”. But, this title has lost its luster.

“The old system is failing,” Yang says. “The market economy has already changed how the sports system works in China.” Schools like this give kids a chance at a lifetime of success, but it’s more likely that they will just end up undereducated and underprepared in a competitive world. This athlete shortage is a serious problem for those who still take Olympic gold seriously.

In 2012, Huang Yubin, the coach of the national gymnastics team lamented in the Jinling Daily that the best days of Chinese gymnastics were coming to an end. “We just don’t have enough talented athletes. The root of the problem is that professional gymnastic teams at the provincial level are failing. The best of our athletes used to come from Hubei, Guangxi, and Hunan Provinces, but they are not delivering athletes that are as good as they used to be.” He was so pessimistic before the London Olympics that he predicted, “Although we got seven gold medals in the 2008 Beijing Olympics, it’s possible that we will not harvest any gold medal in London at all.” Wrong as he was, this disillusionment is not being taken lightly.

Getting to the bottom of the training pyramid reveals at least part of the reason for this athlete shortage. Recruitment, it seems, is where the problems begin. For some sports, it just doesn’t pay to play.

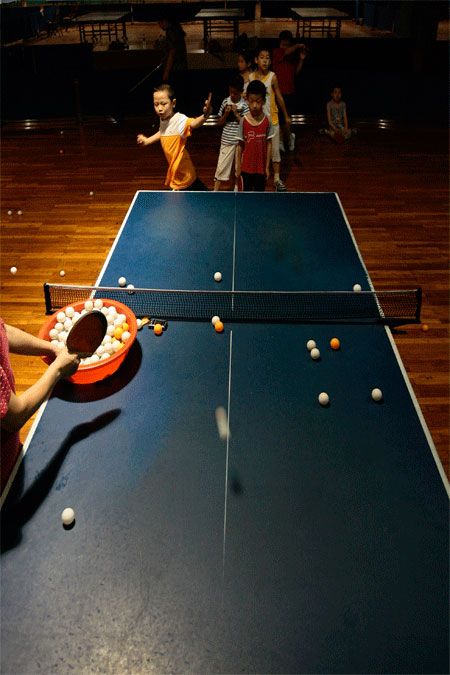

Despite Chinese supremacy in the sport, these youngsters train hard at ping pong in a national sports system that is slowly becoming out-of-date e sports, it just doesn’t pay to play.

Deep in a Beijing basement, a heavy metal door opens to a spacious hall with bright red walls and row after row of green tables. A mixture of crisp ping pong clicks and short sneaker screeches flood into the hallway. Children, from eight to 12, bob up and down in front of tables that look just a bit too tall for them. Every day, these young athletes spend five hours training and only take a 15-minute break for a three-hour session. Their moves are so unbelievably repetitive and uniform that they look like little gifs on a loop, bashing balls back and forth. This is the ping pong training center at Shichahai Sports School. The school is known as “The Cradle of World Champions”, and its alumni include first class athletes and even a few kung fu stars, such as Jet Li (李连杰). Its history can be traced back to the mid-1950s, when sports schools sprang up all over China, following the Soviet Union’s lead in the race for sporting supremacy. Gu Yunfeng, 47, is the general coach of ping pong here, and, like many coaches at the school, he is a former national champion himself.

When speaking about the sport directly, he is not concerned about whether or not his students will excel. “In China, we have the best resources for ping pong. There is a large population of ping pong players, and we have the best coaches in the world. You see, kids are coached by national champions like me from eight-years-old. The problem is, we are so good at it that China is monopolizing the gold medals. It is not a good thing for China to have all the gold medals.”

It has been the talk of the mainstream media for a while— Chinese people are getting tired of games like ping pong where China always wins. Indeed, ping pong is to China as football is to

Brazil, but ratings for the ping pong games have been dropping, hopelessly, for several years. As a matter of fact, viewership and interest only ever pick up when the Chinese team loses unexpectedly. With that comes a loss of sponsorships and earning potential for youngsters hoping to be domestic ping pong stars.

Beijing International Marathon winner Ai Dongmei studied at No.3 Yi’an Primary school (above). Once Ai left the world of sport, all she had to show for it were medals and disfigured feet from years of intense training.

While they are studying, the athletes receive money for food and lodging and are cared for to a reasonable degree. But, ping pong students between 13 and 20 who made their way into the Beijing City Team at that school earn a salary of just 1,000 to 2,000 RMB, not much of a prospect for parents who need their children to look after them. Of course, pay rises dramatically for anyone put on the national team; the chances of this, however, are extremely slim. In the end, when the athletes retire (assuming they’ve been able to make it to the big leagues), they are given a compensation package that varies drastically from province to province.

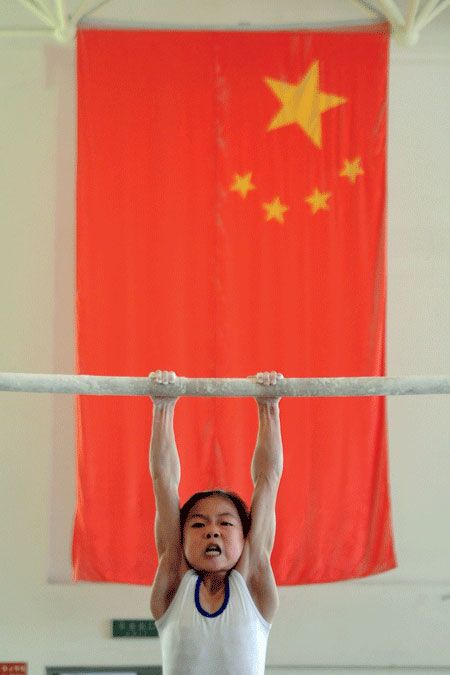

The retirement and welfare of athletes after they’ve done their country proud is another dark side of the national sports system and another reason for lax recruitment, often ending in very depressing headlines. In 2007, Ai Dongmei (艾冬梅), champion at the 1999 Beijing International Marathon was so impoverished that she sold her medals at a price of 1,000 RMB each. Her feet were grotesquely deformed due to the brutal early years of training. With the story out, she received free surgeries from a hospital in Beijing and is now back on her feet. Zhang Shangwu (张尚武), a two-time gymnastics champion at the World University Games, was making a living begging in Beijing’s central commercial area by performing gymnastic tricks under an overpass, jailed twice for theft. More and more stories began to surface of retired athletes living in poverty, with permanent injuries, and without health care.

Yang Yang (杨扬) is the founder of Champion Foundation (冠军基金 Guànjūn Jījīn), a charity that helps athletes rebuild their confidence and enables them to find a new place in the world. She was an ice-skater for 23 years and is now a member of the International Olympic Committee. “About 20 years ago we were still under the planned economy, and over 90 percent of the athletes went on working in the sports system after they retired. Their livelihoods were not a big problem. However, now with the market economy, more and more retired athletes have to look for a job.”

Employment is a big problem, according to Yang Yang, largely because of how sports education is conducted. “Their intensive training keeps them cut off from the outside world. The training system has not changed that much over the years, but the outside world has. There is a huge gap.” What’s worse, there is a great deal of negative social stigma attached to being an athlete.

“To a lot of Chinese people, being an athlete is associated with being undereducated, having underdeveloped social skills and possessing few connections with other people,” Yang Yang claims. “Our skills are not recognized, as if we became worthless after we retired. What we try to do at the Champion Foundation is to try to make them realize that they have useful qualities too, that they shouldn’t feel inferior to university graduates.” The former skater believes these athletes have something to offer, saying they can handle pressure, have a good team spirit and are reliable and trustworthy.

However, while the Champion Foundation may be a boon to athletes who have fallen on hard times, it is hardly a stellar review for the system at large. There is little in this equation that would motivate an average student to devote their life to Olympic success, something with which the public and authorities have seemed utterly obsessed for decades.

Chinese sports were not always so gold greedy. The people of China had their first taste of sporting ecstasy in 1984, when shooter Xu Haifeng (许海峰) won the first Olympic gold in Los Angeles, creating a propaganda firestorm. His story went into Chinese primary school textbooks, which described his last gunshot in excessive detail: “The last bullet, the air around him was frozen. People held their breath. Xu knew the weight of the last bullet—the pride of his motherland was hanging on it… Finally, he pulled the trigger. The ninth ring! Xu won first place by just one ring!… With his last gunshot, Xu Haifeng not only won the first Olympic gold medal for China, but also announced to the whole world that a strong competitor has been added to the arena of the Olympic Games!”

For some time, it was unforgivable for athletes to fail. The ups and downs of Li Ning (李宁), a star athlete in the 1980s, perhaps best embodies the gold fever in the early days of Chinese Olympic hopes. Li was hailed as “The Prince of Gymnastics” in the early 1980s and was welcomed home as a national hero on festooned vehicles paraded through the streets. However, in the 1988 Olympic Games, his palm slipped on a ring and he lost. On his return, hate mail flooded in from all directions, some even contained nooses and knives, suggesting he kill himself. Years later, Li said: “At that time, China had just broken away from utter isolation from the rest of the world. People were just hungry for more gold medals, not sports.”

All this patriotism and glory came to a head with the 2008 Beijing Olympics, when China spared no manpower or expense in hosting and won the most gold medals of any country. However, this gilded circus was the turning point for Chinese Olympic sports. On the last day of the Beijing Olympic Games, writer and social commentator Lin Siyun wrote a blog entitled

“The Trap of Olympic Gold”. He looked back at China’s first gold medal in 1984 and commented, “Xu Haifeng couldn’t have known that with that last gunshot that he also triggered a trap—a trap of Olympic gold medals.” His calculations claimed that the General Sports Bureau’s investments in producing gold medal winners cost around 700 million RMB for each gold medal.

This eight-year-old girl devotes all her time to a national sports system that too often ends in life-altering injuries and poor career prospects

Though this figure is loosely-based and likely inaccurate, it sparked a period of retrospection on what gold medals really mean to China. At the forefront of the controversy was the “national sports system” (举国体制 jǔguó tǐzhì).

Youth Sports Schools are living legacies from the Communist era and are the most fundamental section of the national sports system. The 1980s were the golden times for professional sports schools. Under the planned economy, the government gave jobs to the graduates and an urban hukou (户口, permanent residence permit) to those who came from rural areas. There was never a problem with enrollment. However, as China turned to a market economy in the early 90s, sports schools gradually lost their allure. Although the government still pays for the students’ tuition fees and their training expenses, the students are not given decent training in anything other than the sport in which they major and are left highly vulnerable in an extremely competitive world.

The system dates back to the 1950s when coaches hunted potential talent from all over the country, especially in rural areas, and the government threw money into the training of medal-earning athletes, subsidizing their living expenses. The athletes’ performance in international games represented not just sporting elitism, but also national pride and a symbol of China’s international status.

After the Beijing Olympics, a jokey saying circulated online: “The Olympic Games are like a party where people are playing cards and having fun, and then a professional gambler comes in and wins everyone’s money.” Instead of demanding more gold medals, people are starting to demand budgets for sports venues and equipment that everyone can access.

With their entire futures on the line, few are willing to risk their lives on a shot at gold, and parents are none-too-keen to have their children enter a reality where their child’s financial prospects end with their physical prowess. So, where does all this leave the Chinese system of training super-athletes? No one is certain, but mindsets are changing about Olympic gold, and a national conversation is underway about how the country should handle its athletes on the international stage. It’s pretty clear things are changing; Xu Haifeng’s emphatic success story has already been taken out of primary school textbooks.

Chinese you need

champion: guànjūn, 冠军

athlete: yùndòngyuán, 运动员

train: xùnliàn, 训练

coach: jiàoliàn, 教练

That street vendor used to be the national weightlifting champion. Nàgè tānfàn shì quánguó jǔzhòng guànjūn. 那个摆小摊的曾是全国举重冠军.

My coach is very strict. Wǒ de jiàoliàn shì fēicháng yángé de. 我的教练非常严厉.