Parents demand a return to test-based learning as an official resigns after failed education reforms

“Twenty years from now, classrooms that encourage independent thinking, teamwork, and inquiry-learning will become the mainstream. I have visceral conviction in that!” These are the words of Zhuolu County education bureau director, Hao Jinlun, who tried to change the education system to prepare children for the real world. He resigned three weeks ago.

Hao Jinlun served as director from August 2013 to July 2016, during which time he, according to The Paper, attempted to turn classrooms into “the supermarket of knowledge; the carnival of life”, and spared no efforts promoting a teaching model called Sanyi Santan (三疑三探).

Sanyi Santan, “three inquiries, three explorations,” is an innovative learning method that contains involves answering self-raised questions; discussing questions as a team; reconsidering conclusions and further investigation; applying and expanding knowledge that has been learned—basically an interactive classroom where the teacher no longer has the absolute authority. Students are encouraged to communicate, cooperate, and think critically. This pedagogy achieved success (to different extents) in several other localities before Hao Jinlun decided to apply it to Zhuolu.

May 2014 marked the first few experimental Sanyi Santan classes launched in Zhuolu with an eye to full-scale implementation—Xu Shimin, vice county education bureau director told the Beijing News—but the reform just didn’t perform apace. Schools were told they “must reform” only months later, and by the spring of 2015, Sanyi Santan became the only option for all Zhuolu schools. Surveillance cameras were set up in classrooms to ensure the implementation of Sanyi Santan. “And then things got out of control,” Xu said.

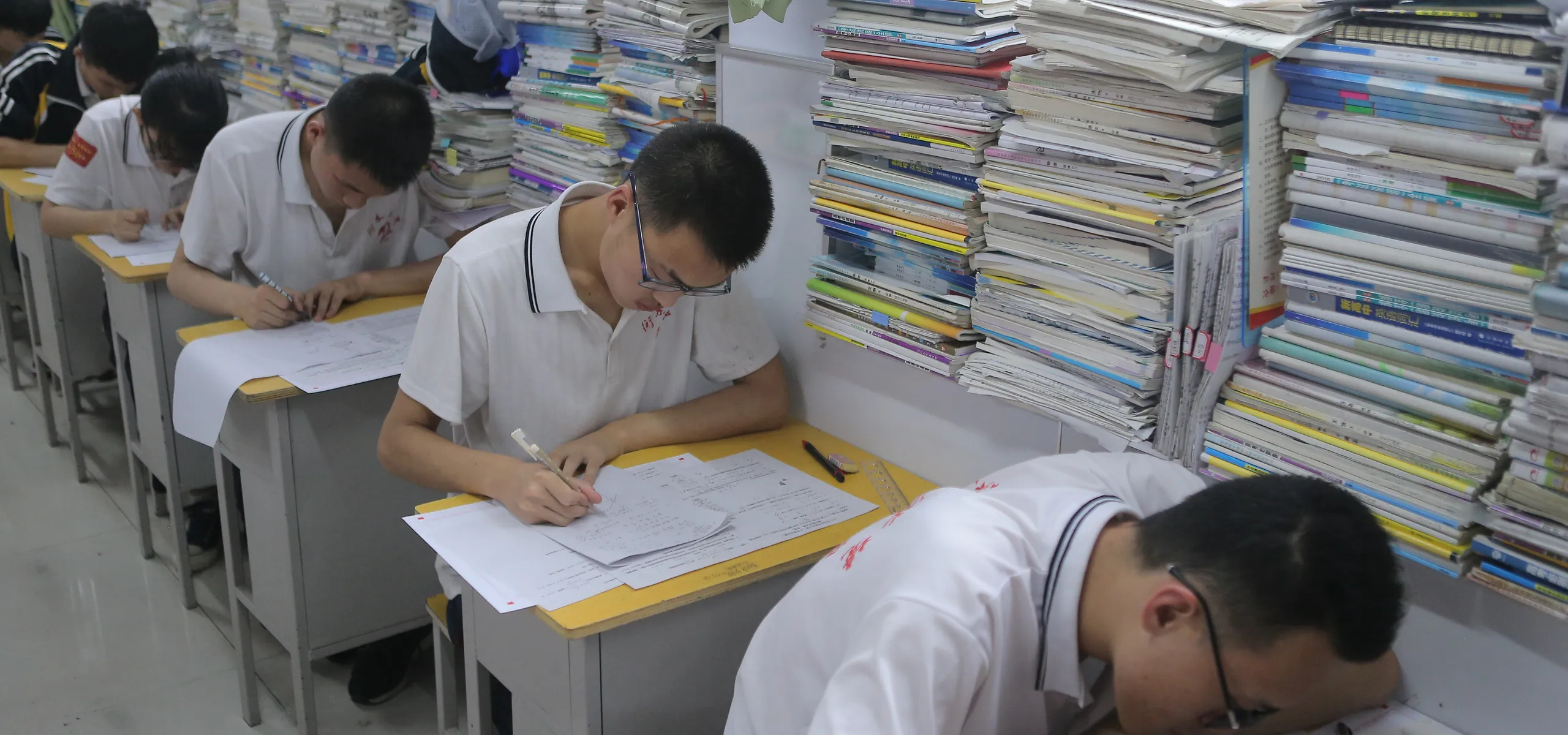

Some Zhuolu parents and teachers strongly disagreed with such radical changes and hoped to return to traditional ways of teaching and learning: teachers dispense as much information as possible, students finish as many exercises as possible, and then get high test scores.

A Chinese teacher at Zhuolu Middle School, identified as Lili, at told the Beijing News that Sanyi Santan was so inefficient that she had to skip some class texts. A history teacher also admitted that Sanyi Santan couldn’t be fully implemented in everyday teaching, expressing concerns about test scores.

In response to the complaints, Hao Jinlun held a “communication meeting” in July 2015 at a Zhuolu Elementary School. Over 2,000 parents participated.

“We asked why he would use our children to experiment, and how could he guarantee the exam scores,” a parent who attended the meeting told the Beijing News.

According to The Paper, on July 4 this year, hundreds of parents in Zhuolu went to the streets in protest, demanding the dismissal of Hao Jinlun. With that, Sanyi Santan reform came to an end in Zhuolu county.

“Reform” has been a key word in the Chinese education sector for decades, since the term “quality education (素质教育)” was first put forward by Deng Xiaoping in 1985. Shortly after the State Council published “decisions on advancing complete quality education.” Nation-scale educational reforms in the following years focused on developing heuristic and discussion-based methods of education under the belief that “alleviating the burden on students” was of great urgency.

The starting point and objectives of Sanyi Santan did meet the requirements of the Central Committee of Communist Party of China on educational reforms, as People’s Daily pointed out, but the lack of a broad consensus is what led to the failure in Zhuolu county.

In the context of the college entrance exam, or gaokao, Sanyi Santan went against the overriding exam-oriented teaching principle and couldn’t prove its efficacy in the short term.

This year in Zhuolu, every high school graduate is competing with 423,100 other gaokao participants in Hebei province. Those who “relax” won’t make it. After 31 years of education reforms in China, “quality education” and “alleviating burdens” are still “useless slogans pleasant to hear,” as news website Sohu put it.

Hao Jinlun wrote in his resignation letter, “But really, the sufferings in life are everywhere…We have to equip the children with the wisdom to defeat those sufferings, rather than just a college degree…We need to teach them how to read, to reason, and to be an upright person.”

Apart from the irreconcilable conflicts between the gaokao and quality education, Hao Jinlun also alleged “political intrigue” was a factor in Zhuolu’s reform failure.

“Someone thought the reform affected stability, and wanted to stop it,” Hao told the Beijing News, “I have too many enemies. Several ‘leaders’ used to ask me to do things that violated my principles. And the other day at the protest, some protesters didn’t have children affected by Sanyi Santan, or didn’t have children at all.”

Given the current situation in Zhuolu, Hao said he “entirely agreed to return to traditional teaching methods,” but was unwilling to lead that task.