How will China save its vanishing local operas?

Everyone used to know when Pei Guansheng’s opera troupe came to town. In the late 1970s and early 80s, his 50 performers would tour across northwestern China’s Gansu and Shaanxi provinces, sometimes performing up to three shows a day to rapt audiences who sat on stools from dawn to dusk.

Back then, opera was “the most widespread form of entertainment,” says Pei, whose troupe, which he managed until 1984, specialized in a form of opera called Qinqiang. “Everyone could hum a little bit from famous works.”

But today, Qinqiang, like other forms of traditional opera in China, is fighting for its life. “What the smartphone is doing now to television, is the same as what television did to opera,” says Pei. While the government has labeled traditional opera as “cultural heritage” and funneled funding into training new artists and supporting troupes, much of the money has gone toward Peking opera, called “China’s national opera” by the State Council, the country’s cabinet. That has left hundreds of lesser-known regional and local varieties struggling to find audiences and new performers.

According to statistics published by China’s Ministry of Culture in 2013, the most recent year with such data available, an average of three traditional Chinese operas have disappeared every two years since 1982. This means that 60 forms of opera have died out or become nearly extinct—that is, they only have a few remaining performers—since the 1980s, leaving behind just 348 different types of opera as of 2017.

Speaking to those who continue to make a living from opera, from university educated singers at Beijing’s biggest venues to grassroots warblers at village funerals, TWOC hears the common complaint that the art is no longer in vogue among younger Chinese people. “Nowadays, there are too many forms of art in society, as well as movies and TV networks,” says Feng Ziyang, a senior performer of northern China’s Pingju opera at a state-run theater in Shenyang, the capital of Liaoning province.

Chinese opera, or xiqu (戏曲), is believed to have originated in ancient shamanistic ceremonies and the court dances of successive kingdoms and dynasties. It initially took the form of songs and dances performed outdoors in rural communities as part of religious rituals, from praying for a good harvest to ending an epidemic. Later, it evolved into forms of mass entertainment that drew crowds from across the local region.

The first written opera scripts appeared in the 13th century. Many regional operas recycle the same historical or legendary stories, but differ by dialect, musical style, and performance. For example, Yue opera from the Yangtze Delta only uses female performers; Sichuan opera features fire-breathing and lightning-fast mask changes; and southeastern China’s Nuo opera is known for its uncanny masks. The Qinqiang style, which is from Shaanxi, is characterized by harsh singing that practitioners literally call “yelling.” “It means singing your heart out, as loudly as you can,” says Pei.

Opera’s grassroots popularity made it a key vehicle of propaganda for the party, which commissioned new works based on revolutionary tales and values—and excised superstition and sexual references from older scripts—after founding the modern Chinese state in 1949. Opera singers, traditionally an ostracized class, became part of the establishment: The Peking opera star Mei Lanfang was even given a place on the rostrum when Mao Zedong announced the establishment of the People’s Republic of China.

In urban areas, the government set up “opera houses” where troupes could train new members and rehearse, and moved performances onto Western-style theater stages in lieu of ramshackle outdoor scaffolds. In each county, the state registered opera troupes and gave guaranteed, cradle-to-grave jobs to artists who produced or performed operas.

During China’s market-oriented reforms of the 1970s and 80s, state funding was withdrawn from most troupes. The new urban middle class, who might have made up the market to support opera in the government’s stead, had the option to spend their money instead on the Western music and other cultural imports now flowing into China.

Unlike, say, the teaching of Shakespeare in the English-speaking world, younger people in China received little education about opera as a serious form of cultural heritage, leading to extreme “cultural alienation,” says Haili Ma, an associate professor of performance and creative economy at Leeds University and a former Yue opera performer who has researched the state of the tradition in China today. Part of this research includes an interview with a performer who witnessed bored students at Tongji University crawling en masse through a hole in the roof to escape an opera performance in the late 1990s to continue studying for their exams.

“Theater opera is in decline. This is an indisputable fact,” says Feng, the Shenyang-based performer. “I say that if Mei Lanfang was alive today, even he wouldn’t necessarily attract much of an audience.”

“Young people nowadays don’t sing Qinqiang,” Wu Hui (pseudonym), a performer and troupe manager in a small city in southeastern Shaanxi, who later asked to remove her real name from this story, booms in a voice appropriately strong for her profession. Wu, a woman in her 50s who calls herself “a real peasant,” took up opera training at 19 years old and was taught at a small local training school in the early 1980s. Her troupe is motivated by passion for the art rather than by money, she says.

That is perhaps just as well. Wu’s troupe only receives intermittent funding from the local culture and tourism bureau, and she makes up the difference from membership fees and her own private funds. But it still isn’t enough. “I don’t have money to pay the artists. Recently, I performed for the local government. It has been three months and I haven’t got the 8,000 yuan (1,238 USD) I spent [in overhead costs] back,” she complains. “If you don’t know people [in the local government], no matter how good your troupe is, it’s hard to get support.”

Following the Ministry of Culture’s report on vanishing operas, the State Council issued a notice in 2015 urging local governments to use subsidies to protect and revitalize Peking opera, Kunqu, and other local operas. The move entitled small troupes, troupes in poorer areas, and state-run troupes below the county level to state funding, tax exemptions, and money to buy equipment. Students majoring in opera at secondary vocational schools could also receive free tuition.

Despite the ostensible support for all forms of opera, the policies often favored the Peking variety that the party has used since the mid-1950s to promote a unified national culture, thanks in part to the international renown of Mei—the performer who shared a podium with Mao—and to the fact that it is sung in the Beijing dialect, similar to the form of Mandarin that the government pushed as a national language.

According to the National Bureau of Statistics, Peking opera troupes received an average of 68 million RMB per year in total subsidies between 2008 and 2012, the latest year for which data is publicly available. Over the same period, the total subsidies given to every other type of “opera, dance-drama, and song-and-dance” troupe only slightly exceeded that amount, with 76 million yuan per year.

Opera troupes lean on the government not only for funds, but to get audiences for their shows. When the Pingju troupe Feng is part of performs in Beijing, the municipal government buys up tickets and gives them away for free in suburban villages, he says. The troupe performs both well-known titles and newer operas designed to instill social morals. “My troupe’s original productions basically all have to do with transmitting positive energy,” Feng says, using a Party buzzword.

One show in the repertoire, Yueqing, premiered in 2014 and tells the modern-day story of a man who commits suicide by causing a car accident. Years later, his wife finds out the truth and reconciles with the other driver, who had been working hard to repay his debt to her family all this time.

The amount and form of state aid varies from region to region. Since Wu, the Shaanxi-based opera singer, registered her troupe around five years ago, she has had to put on performances to celebrate the Party and support major policies like poverty alleviation. “We have to do these performances, even though we aren’t paid to,” she says.

Thanks to the subsidies, Wu can now buy props, costumes, and sound systems. The government also provides her company with paid gigs. The budget doesn’t stretch to travel expenses, meaning her performers must pay out of their own pockets if they want to travel outside their city.

The subsidies also do not solve other entrenched problems like recruiting younger performers and minting young opera fans. Although Wu is teaching three children to perform, her troupe of around 50 people is “basically between 45 and 70 years old,” she says.

Part of the problem is that opera training is lengthy, grueling and results in low-paid work. Despite his long years of experience, Feng’s monthly salary is only around 4,500 RMB, after taxes and social security payments, slightly over half the average salary in his city.

“Around 30 youngsters recently completed their training with our troupe,” says Feng. He reckons they still need three to four more years of doing non-singing background roles before they “no longer get nervous on stage and can open their mouths,” then up to seven years of singing minor parts before they are ready for the main roles. “If we can get four or five [first-class performers] out of 30 [apprentices], that’s already very good,” he says.

In recent years, many opera troupes, including Feng’s, have tried to attract younger audiences by putting on performances for children, livestreaming shows on short-video apps like Kuaishou and Douyin—China’s TikTok twin. Feng himself can get up to 2,000 views per stream, but only 100 regular fans. The hugely popular video game Honor of Kings has also introduced opera-themed player avatars.

But their efforts have only had a limited impact. Ma, the associate professor, says one of her doctoral candidates found that dozens of gamers felt the avatars bore little cultural relevance to their lives. The student recently surveyed around 100 players who did not use the opera-themed avatars to find out why. “Some of the answers were ‘They scream like Peking opera, scream like ghosts; I don’t like it, it has no cultural relevance to us,’” says Ma.

The industry’s inherent conservatism is another problem, Ma says. “Unfortunately, the traditionalists, the people who do have the voice to tell the government what to do, who hold the important positions like heads of opera schools and colleges…these people don’t want to change.”

Additionally, younger people are often put off by the themes of older operas, Wu says, citing The Seedling Vendor, an opera in her troupe’s repertoire that urges women to obey their in-laws. While some older audience members in the villages enjoy the work, “some daughters-in-law [today] just don’t like this kind of content,” she admits.

Ma says it remains to be seen whether the government’s policies are rekindling the popularity of traditional opera in different regions. “Shanghai’s different from Beijing, and Shanxi is different from Shanghai. You have to really break them down into very complicated socioeconomic platforms.”

While a lack of attendance records makes it difficult to pinpoint the level of interest in opera in the countryside, Ma’s research suggests that some local forms continue to thrive in rural communities.

For instance, operas continue to serve important roles as rituals to appease the gods in rural areas near the city of Quanzhou in southeastern China’s Fujian province. Compared to the city’s state-run opera house, which struggles to find audiences, opera performances crowdfunded by local families are still part of important ritual celebrations in some rural communities.

A makeshift theater Ma visited in 2016, around 30 minutes’ drive from Quanzhou, was built in celebration of a new ancestral hall for a wealthy local family. The performance began with actors dressed as the Eight Daoist Immortals offering incense to the family deities, and later featured military reenactments and clowns uttering obscenities to spark laughter in the audience.

Funding for both performances came not from the government, but from family members working overseas. “In central parts of China, because the ancestral lineage link is weaker, they have to rely quite closely on the government,” Ma says, “whereas toward the eastern coast there continues to be a strong global [diaspora] network [with] more independence and therefore more diverse ritual opera activities.”

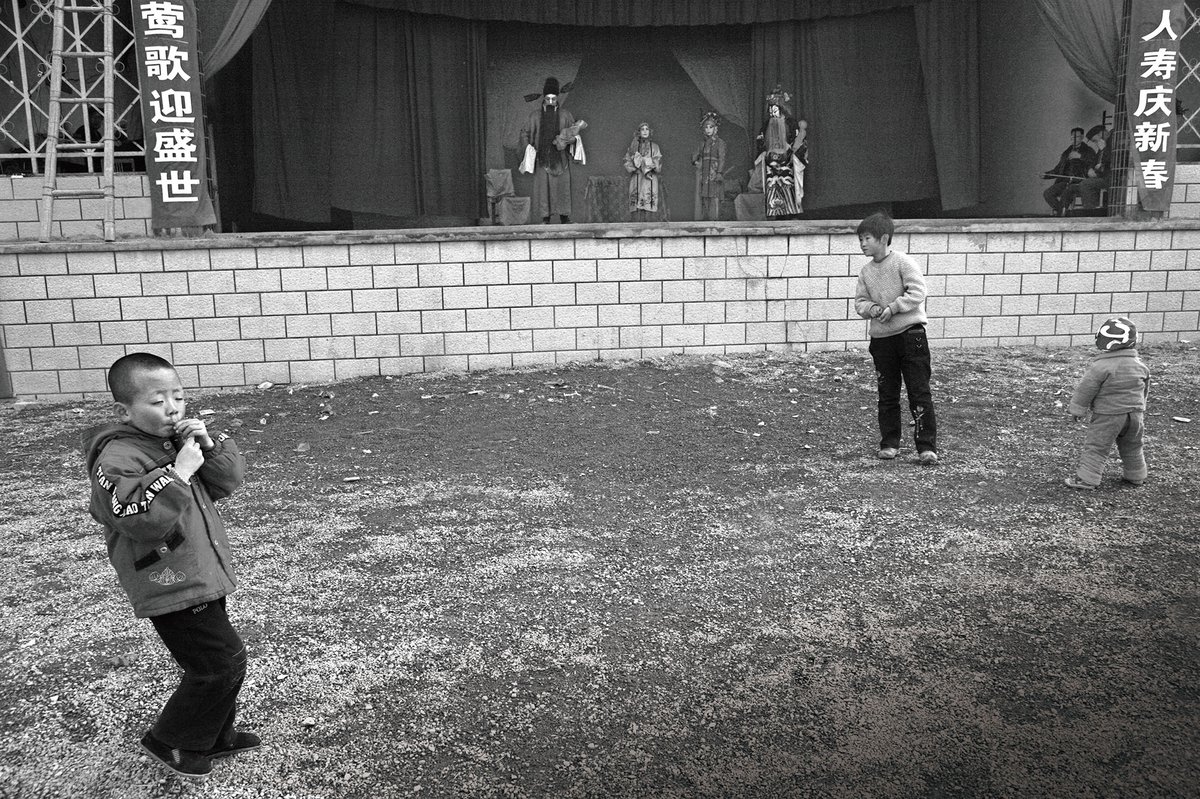

Similarly, in Shaanxi, rural families have paid Wu’s Qinqiang troupe to sing at weddings and funerals, both for ceremony and entertainment. She says rural families still find it important to put on a show during major life events to display their filial piety and family bond before the whole community.

“Are the middle class, after all these years of nurturing, interested in plain Chinese opera? The answer is no,” says Ma, adding that separating opera from its community roots and placing it in hushed urban theaters is contributing to its decline.

But she points to the findings of her student, which indicate that some urban Chinese are now consuming opera-themed products, meaning that Chinese opera retains its cultural value if not its form in Chinese society. “It does give [Chinese people] a sense of identity,” Ma says. “Over the past decade, the government has been trying to educate students about [the value of] Chinese culture…so it is now beginning to pay off.”

– Additional reporting by Jenna Lu and Anita He (贺文文)

The Uncertain Future of Grassroots Chinese Opera is a story from our issue, “Upstaged.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.