The Wanggongchang Explosion continues to mystify historians almost 400 years later

Industrial accidents are hardly news in China. But sometimes an industrial accident wipes out half a city, kills 20,000 people, and enters the annals of history as a story weird enough to be worthy of its own X-File.

In 1626, the Wanggongchang Armory exploded taking most of southwest Beijing with it. But to this day, nobody can agree exactly what happened. It was an explosion so immense that it was heard beyond the Great Wall over 150 kilometers from the blast site. Reports of a “mushroom shaped” cloud hanging over Beijing after the accident have provided grist for historical conspiracy theorists ever since.

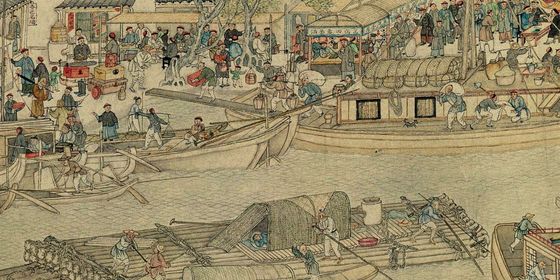

Wanggongchang was one of several arms depots in the Ming-era capital. Supervised by the Ministry of Public Works, the armories were staffed by between 70 and 80 people who worked there to manufacture and store arrows, bladed weapons, gunpowder, and cannons. The armories were critical to the capital’s security and the defense of the realm. By the early 17th century, the armies of the Ming Empire competed in an escalating arms race with the Manchus in Northeast Asia. New guns—some of them close copies of European cannons brought to Asia by the Portuguese—could be a difference maker in holding on to territory and keeping the Manchus at bay.

To keep these arms from falling into the hands of the enemy, the Ming army and the Ministry of Public Works built the factories within the high and thick walls of the capital. Unfortunately, that was where most of the people lived too. It wasn’t long before the consequences of putting an explosives factory in a residential neighborhood would become tragically apparent.

At around nine in the morning of May 30, 1626, a plume of smoke arose from the Wanggongchang Armory followed by an immense explosion. Almost everything within an area of two square kilometers surrounding the site was instantly obliterated. About half of Beijing, from Xuanwumen Gate in the South to today’s West Chang’an Boulevard in the North, was affected.

Guard units stationed as far away as Tongzhou, nearly 40 kilometers east, reported hearing the blast and feeling the earth tremble. Other area outposts thought an earthquake had struck the capital.

As the smoke cleared, debris began raining down all over the city. One account reported that a 5,000-pound statue was blown clear across the city. Bricks, rooftops, and other building materials pelted survivors as they ran for cover. Gory tales persist of body parts, noses, ears, arms, and worse, falling from the sky.

The bodies of those victims who didn’t disintegrate straight away were later found stripped of clothing and covered in a strange residue.

From what was left of southwest Beijing, an enormous cloud in the shape of a mushroom rose into the sky.

Later analysis calculated the blast as the equivalent of nearly 20,000 tons of TNT, an explosion roughly the equivalent of the atomic bomb which destroyed Hiroshima in 1945.

Contemporary records suggest that it was either a spark which then ignited gunpowder stores or a buildup of flammable gasses. Certainly, large quantities of explosive and flammable materials were being stored on site.

But the size of the explosion—and the reports of the mushroom-shaped clouds—have intrigued conspiracy theorists for centuries. Some speculate that the blast was caused by a freak meteor while other, even more outlandish, theories, have implicated supernatural forces and even an interplanetary nuclear strike on Beijing.

As Ming dynasty records are woefully devoid of references to alien first-strike capabilities, we may never know for sure what caused the blast.

The court was less concerned about extraterrestrials than they were about the cosmologic and political implications of such a large disaster occurring right in the heart of the capital. The Tianqi Emperor (天启帝) was hardly a model monarch. He was an odd young man, more comfortable in a carpenter’s shop than reading documents. Power devolved to his mother and the eunuchs, in particular, the infamous Wei Zhongxian (魏忠贤), one of the most corrupt officials in Chinese history. A mysterious explosion might easily be interpreted as a sign of Heaven’s displeasure. Many groups of officials, including those associated with the Donglin Academy, who were some of the biggest critics of the court, were quick to make the case that an event of this nature could mean that the emperor’s mandate was in jeopardy.

A conference held in Beijing in 1986 explored all the possible causes of the incident from a spontaneous explosion of black powder to a natural gas leak, and the more far-fetched theories of meteorites, hidden volcanoes, and an underground nuclear discharge. The conference participants ultimately concluded that an earthquake resulted in a release of gasses at the site which ignited a massive explosion and firestorm which destroyed the area.

One theory, put forth in a 2013 paper by researchers in the United States and China, argued that the disaster was the work of a giant tornado. A catastrophic twister caused the explosion and was also responsible for much of the damage throughout the city, including the stories of large objects thrown for miles and bodies found stripped entirely of the clothing.

Whatever the cause, the Wanggongchang Explosion of 1626 ranks as one of the worst peacetime explosions in history and remains one of the deadliest incidents ever to befall the city of Beijing.

This is a story from our archives: It was originally published in October 2016 in our issue “Gender Equality”. Check out our online store for more issues you can buy!