The most down-to-earth character of them all

During the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE), a thief stole a jade ring from a temple honoring Emperor Gaozu, the dynasty’s founder. Zhang Shizhi (张释之), a chamberlain for law enforcement renowned for his fairness and adherence to the law, tracked down the criminal and executed him. But this earned the ire of the Emperor Wen, who felt that the thief’s whole family should be executed and their property confiscated for this grave offense against his ancestor.

In response, Zhang took off his hat to signal that he was resigning from his post, saying, “If we exterminate a whole family for one person stealing, how would you punish someone who dug out a handful of yellow dust from Emperor Gaozu’s tomb?” This story, which was recorded in the Records of the Grand Historian (《史记》) by Sima Qian (司马迁) in the first century BCE, gave rise to the idiom 一抔黄土 (yì póu huángtǔ, a handful of yellow dust), which refers to an insignificant force.

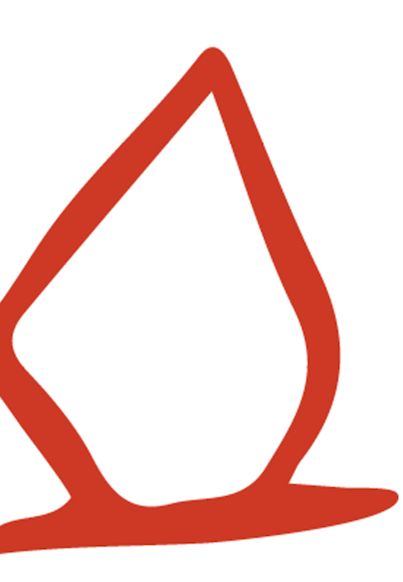

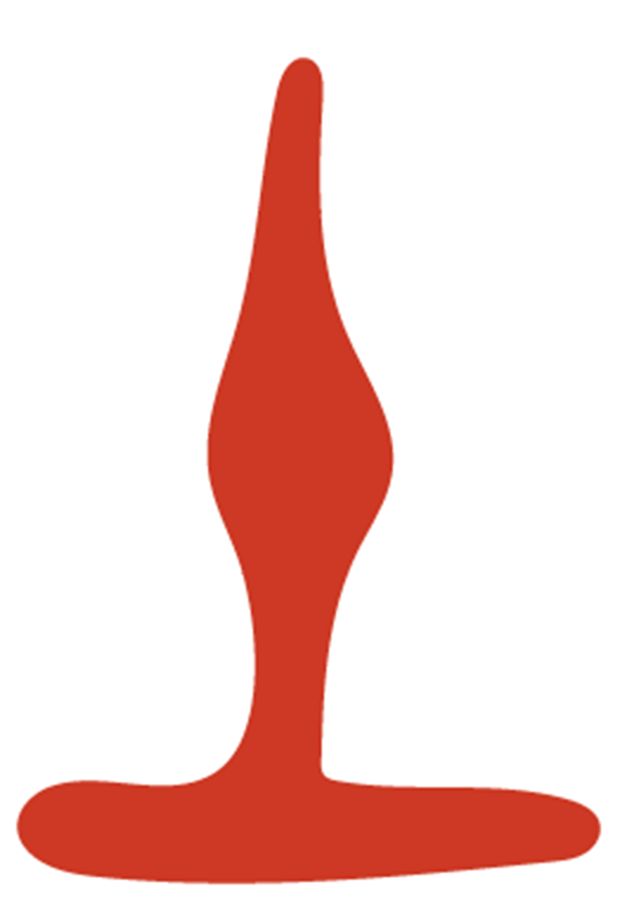

Ever since its first appearance, the character 土 (tǔ) has been connected with dust, soil, or land. The character’s earliest form appeared in oracle bone script, as the image of a mound rising from the ground. The character took its current form as early as the Qin dynasty (221 – 206 BCE) in seal script. The ancient Analytical Dictionary of Chinese Characters (《说文解字》) defines 土 as “the soils that gave birth to everything.” The philosopher Xunzi (荀子), who lived in the third century BCE, is credited with inventing the idiom 积土成山,风雨兴焉 (jītǔ chéngshān, fēngyǔ xīng yān, the accumulation of soil makes mountains, where wind and rain prosper) to encourage people to persevere in their studies.

When 土 and 地 (dì, “the earth”) combined, it became 土地 (tǔdì), meaning “land.” The character could also be used figuratively to refer to one’s homeland, which is 乡土 (xiāngtǔ), 故土 (gùtǔ), or 本土 (běntǔ). Extended even further, there is 国土 (guótǔ), which refers to a country’s territory. Confucius is credited with the saying 君子怀德,小人怀土 (jūnzǐ huái dé, xiǎorén huái tǔ), which means “the superior man thinks of virtue, the small man thinks of his homeland.”

Other metaphors involving 土, such as 一抔黄土, are based on the association of dirt with lowliness or insignificance. Literally, 土腥气 (tǔxīngqì) means the smell of the soil, and there is another term that does not smell good—粪土 (fèntǔ, manure). When someone doesn’t value money that much, there’s the phrase “treating money like manure”: 视钱财如粪土 (shì qiáncái rú fèntǔ). In his poem “Changsha: To the Tune of Qin Yuan Chun (《沁园春•长沙》),” Mao Zedong wrote “粪土当年万户侯 (fèntǔ dāngnián wànhùhóu, “we counted the mighty no more than muck”) to show his disgust for the people in power.

Meanwhile, those who waste money are said to 挥金如土 (huījīn rútǔ, spend money like dirt). When a person realizes they’ve squandered all their money, they might become 面如土色 (miànrútǔsè, “face as gray as dirt”), which indicates a huge panic. But there is no need to worry, as there will always be another chance to 卷土重来 (juǎntǔ chónglái, “to return in a swirl of dust”), which means to make a comeback.

In the modern day, 土’s association with agriculture and soil can give it a negative connotation. As an adjective, 土 describes something that is rural and therefore backward, though in recent years its meaning has gotten more positive as people develop more appreciation for local culture and organic products. 土音 (tǔyīn) and 土话 (tǔhuà) refer to local dialects; 土货 (tǔhuò) and 土产 (tǔchǎn) refer to local agricultural products; and 土方 (tǔfāng) and 土法 (tǔfǎ) to folk recipes or remedies. 乡土文学 (xiāngtǔ wénxué) refers to literature with rural themes, often written by authors who were 土生土长 (tǔshēng tǔzhǎng, native-born and raised) in the areas where the work is set. A less flattering name for rural people is 土包子 (tǔbāozi, bumpkin), who are described as 土里土气 (tǔlitǔqì, “rustic”).

It’s not a good idea to use these pejorative terms about rural people—after all, as a proverb says, we all “来于尘土,归于尘土 (lái yú chéntǔ, guī yú chéntǔ, come from the dust and return to the dust).” We should be respectful of the 土 that brings life to everything.

On the Character: 土 is a story from our issue, “Promised Land.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.