A look behind the ancient Chinese tradition of corpse walking

Last November, a young Chinese man was detained while traveling across Southern China’s Yunnan Province for suspicious behavior, and it was behavior suspicious indeed: he was traveling with a dead body. The dead make for awkward traveling companions, but after some questioning, it was proved to the police that the dead man was, in fact, the young man’s father. This traveler was trying to get his father’s body back to their hometown in Hebei several provinces away. He had already walked more than 600 kilometers on his “corpse walking” endeavor before being stopped by the police.

Seemingly strange, the practice of walking corpses has long been a part of Chinese mourning. While the young lad in this tale is by no means a professional corpse walker, the profession and superstition still exists despite a severe decline in modern times. “Herding corpses” or 赶尸, is the tradition of transporting corpses back to their hometowns. Legend has it that, in the mountainous Xiangxi (湘西) of Hunan Province, one could sometimes catch a glimpse of the “dead men’s march” where the corpse walker leads a line of dead bodies along narrow roads.

According to various corpse walking legends prevalent in Western Hunan, the technique was rumored to be Miao witchcraft; the Miao ethnic minority is famous for their supernatural gifts, called gushu (蛊术). Corpse walking is believed to be a form of gushu sorcery. It also invokes and borrows supernatural concepts from the I Ching.

Usually, the procession of corpses is led by two Taoist monks, one the master and the other his student. If a man were to die in another town, the dead person’s relatives would travel there and ask a Taoist monk to take the body back to their hometown, an extremely important tradition in Chinese culture as a person’s soul, body, home, and land are closely entwined. If the body cannot go home, the soul is lost forever in the world after death, suffering everlasting turmoil. Corpse walking was born out of filial piety, feng shui, and ancestor worship, and it contributes to the pervasiveness of such traditions.

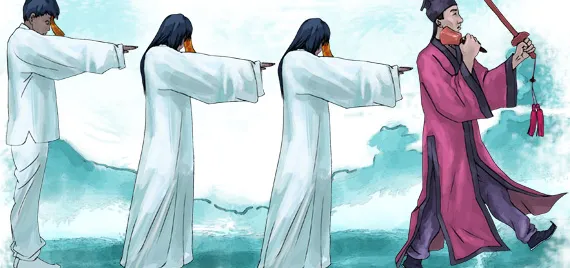

Written records of corpse walking are few, and oral accounts vary. It is said that when the Taoist priest arrives, he first checks the deceased’s date of birth, then, uttering spells, uses a peach wood sword (a spiritual weapon used for exorcisms in Taoism) to check whether the spirit will obey his commands. The priest doesn’t take off with just one corpse; he waits for other orders to come in so that they can all leave together. Before they set off on their journey, the priest performs a ritual; he sticks a symbolic talisman on the forehead of each dead body and utters incantations. The talisman is yellow paper with red ink depicting characters, images, or symbols that can conjure power and manifest energy. The bodies then rise up and follow the priest. As rigor mortis has set in, the dead can only hop; these same hopping zombies have inspired a number of Hong Kong zombie films. This, in turn, popularized the common concept that Chinese zombies hop to go forward and stretch out their arms for mobility.

If making the dead walk again sounds unbelievable (and it should), what happens next is even more interesting. In order to lead the spirits, the priests shake bells with supernatural powers to lead wandering souls, striking gongs to alert travelers and residents of their passing; such a warning is believed necessary, as the dead are thought to bring bad luck and evil spirits. Traveling winding, mountainous paths can be exhausting, and—as daytime is unfit for the dead—there were often “dead body inns” for corpse walkers and corpses to rest. These inns are open for corpse walking only, and, because death waits for no one, they were open all year round. It is said that the corpses rest behind the doors lined up against the wall. And, due to the priest’s special recipe of incantations and ceremonial sword-waving, the dead bodies never decay regardless of the time traveled or the weather. While traveling, the priest lines them up with a rope, each wearing a tall hat, hopping one after another and veiled by the darkness of night.

For the rest of this article please get a copy of our latest issue of The World Of Chinese Magazine