China’s independent filmmakers compete for funding in a risky market

“I’m still surprised by the doors that are opened here and the kinds of meetings you can get into,” says Chinese-American filmmaker Wen Ren, reflecting on his experiences with independent filmmaking. “If you have a good idea, there are lots of opportunities that can get you in the door.”

Wen, whose career was kicked off after his short sci-fi film Café Glass premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival, splits his time between Beijing and Los Angeles. His ultimate goal is to work on co-productions between China and Hollywood, but in the meantime he is engaged in making a webseries entitled Gushihui which is reminiscent of a Chinese X-Files.When it comes to the topic of “independent filmmaking” in China, he is introspective about what that term entails.

It’s difficult to define what exactly constitutes an independent film in China because even in the Western context it’s a fairly subjective term. It’s possible to categorize independent films as those that are self-funded, but given the wide variety of funding sources available to the filmmaker, this may be arbitrary and restrict the pool to a negligible number of films.

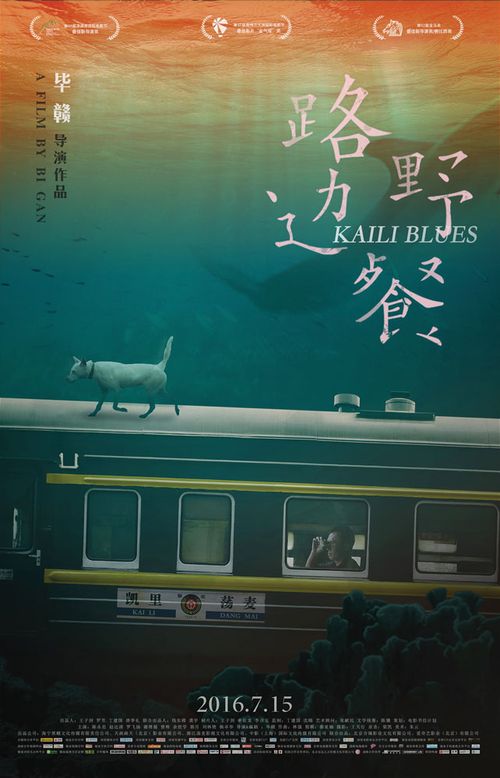

Arguably the independent film with the highest profile in 2016 was Kaili Blues. Director Bi Gan, fresh out of film school, crafted a haunting look at a father and his lost son, but the film’s real star was the director’s hometown: Kaili, Guizhou province. The film was made on a shoestring budget, aided by the Bi’s casting of his family members and low production costs in an area like Kaili. It was also fairly niche, with Buddhist scripture interspersed between long scenes of riding motorbikes through lush, wet, impoverished landscapes.

He was still funded by multiple investors.

Poster for Kaili Blues

Aside from finding a studio or a wealthy patron, there are emerging avenues for funding that have been brought about by the ubiquity of the internet. Online films and TV series are often funded by studios and offer one avenue for creative expression, and there is the potential to become a live-streaming celebrity, but these funding sources aren’t necessarily suited to independent film. There are, however, a small but growing number of Kickstarterstyle crowdfunding websites. While these don’t specialize in films, “micro-movie projects” are a popular category of aspiring business ventures. Typing in “微电影” (micro-film) on one of China’s larger crowdfunding sites, Zhongchouwang, brings up a range of projects seeking investors.

Categorizing a film by funding sources is somewhat difficult; instead, it becomes easier to define an independent film by its fairly low budget and the director’s total creative control. Here, though, it is important to keep in mind that even those filmmakers who are dedicated to creating art films find they have to split their time between commercial endeavors and their own projects.

Wun Yip recently returned to Beijing after working as second assistant director on the upcoming film Bitter Flowers, which focuses on a Chinese family living in Paris and China. She said that work like this not only provided an income but also a chance to observe and take lessons from other productions and forge new contacts, both of which are incredibly important to independent filmmaking. But long before Bitter Flowers, Wun had learned the importance of these experiences the hard way.

Filming of Wun Yip’s Next Minute, a 10-minute film about an open-mic night (Wun Yip)

When she arrived in Beijing in 2008 after spending years studying film and anthropology in the US, she knew she wanted to create a film and had the concept in mind. Bringing her vision to the screen as a short film took three years. The result was Next Minute, a 10-minute film about an open-mic night. She is proud of the film but describes it as a steep learning curve and a difficult introduction to the filmmaking experience.

“I’d had the idea for years, but once I was working on it I guess I spent about a year working on the script and finding crew. At one point, the crew fell apart and I had to assemble a new team,” Wun says. “It started out as a team of 10 people to create 10 minutes [of film], but by the end it involved 60 people.”

She said a turning point was when she met a producer from Hong Kong, who was able to help her make connections and steer the production. This comes back to another key aspect of filmmaking success—a lot is about who you know. This is partly because the support structures in China are quite different.

From the set of Wun Yip’s Shadow (Wun Yip)

“There is a lack of resources for filmmakers in China. In the US, there are places you can go where you can get information on every step of the filmmaking process. Here, you need to network,” Wun says.

For young filmmakers, support from film schools is one way to get off the ground. Beijing Film Academy graduate Liang Shuang said that she doesn’t define herself as an “independent” filmmaker, because of the school support she received, which included funding and equipment.

“Even though the production team is something I formed on my own—including cinematographers, actors, and locations—I received help from a lot of people. Even though I invested a lot of work involved in making the film, there were a lot of classmates who helped me complete it, and the funding [was] not something I had to come up with, so I don’t consider myself an independent filmmaker,” Liang says. “Also, the marketing after production and lots of other steps such as the film’s copyright and distribution—I didn’t do any of that. I guess you could say I was just the creator.”

Wen, though, points out that the less-organized state of the industry in China has its advantages. “In L.A. you find that everything is dominated by the big six studios, but here there are many sources of funding,” he says. “There are countless studios and people who have made money in areas like real estate and other lucrative ventures who want to invest in the film industry.”

Film festival culture is another area in which there is wide discrepancy between the Western and Chinese experience. A hopeful young independent filmmaker in the US might hit a film festival and win recognition through a creative idea, but in China, that path, while still viable, is a bit murkier.

China has no Sundance or Tribeca Film Festivals, but that isn’t to say there is no film festival culture; it’s just struggling for recognition. The highest-profile independent film festival was probably the Beijing Independent Film Festival, but sadly, when its prominence was at its zenith it was repeatedly shut down before being totally snuffed out of existence. In August 2014, the 11th festival faced disruptions and became limited to a tiny audience. Since then it has been out of action.

Meanwhile, the Beijing International Film Festival, which shares the same initials, was trumpeted loudly in state media. In 2016, it drew Hollywood stars including Natalie Portman to attend. This festival, though, is much more a Chinese Oscars than it is a Sundance.

There are other independent film festivals in China. Established in 2003, the China Independent Film Festival is still going strong, with its most recent festival taking place in December 2016.Beyond the organized festivals, anecdotal experiences indicate that it is common for film aficionados to organize small-scale film events in their own homes. There is also a vibrant Chinese film festival community outside of China’s borders. Canada, for example, has a significant number of film festivals that focus on or highlight Chinese films, such as the Golden Panda International Short Film Festival co-organized by CNTV, and the Canada China International Film Festival in Montreal. In 2015, the film Drunk Beauty won the Golden Panda’s Best Picture award.

Drunk Beauty director Yao Qingtao tells TWOC that he thinks some of the biggest challenges for aspiring Chinese filmmakers are related to their own development. “Film has its own artistic value and unique artistry, and within those techniques there is a difference between quality and quantity. A lot of young filmmakers have seen a lot [of films] but when it comes to actually creating, they don’t know where to start, or they start second-guessing themselves.”

“The film market, from the perspective of subject matter, is very diverse. For a young filmmaker who lacks influence and ability to attract capital, my suggestion is: Don’t be greedy. You have to start small.”

The go-to question for foreigners peering into the Chinese film scene is the influence that the authorities exert when it comes to approving films for distribution. This in many ways is less of an issue for small independent filmmakers, who are less likely to seek wide distribution and run the approvals gauntlet, but it’s an issue which will eventually confront them as they meet success and move up the industry’s food chain.

Before even beginning to come to grips with the regulations, it’s important to be aware that there is no content ratings system in China. Instead, censors decide whether or not a film should be allowed distribution, so films intended for a wide audience must be submitted to the State Administration of Press, Publications, Radio, Film, and Television (SAPPRFT). Foreign productions must be licensed to be shown on the Chinese internet or television, and this is generally through a co-production arrangement with a Chinese company.

There are vague commands that films should “serve socialism and the people” but very little specific information on what this actually entails. The Film Industry Promotion Law, the first actual overarching law (as opposed to regulation) that relates to the film industry, will go into effect as of March 2017, and while SAPPRFT has said it reduces oversight from censors, this isn’t necessarily the boon it would appear to be.

Currently, a filmmaker who wants wide distribution must submit their entire script to SAPPRFT, though the new law will require only an outline. Under the new law, the bodies that approve the scripts will be decentralized and possibly localized to the provincial level. Until the law goes into effect it is difficult to determine the effect it will have on filmmakers, though critics say that it could make receiving investment more difficult; in the event that the approvals (or withdrawals of approval) occur later on in the filmmaking process, investors may be more skittish about sinking money into a risky project.

The new law also indicates that films need a license before any distribution, be it in China or overseas—and this could be a problem for films that intend to use film festivals to promote themselves, as these films currently often don’t attempt to get licenses. China Film Insider recently reported that film heavyweight Feng Xiaogang’s I Am Not Madame Bovary did not receive this license before it was submitted to (and won Best Film at) the San Sebastián International Film Festival.

One can only speculate at this point the effect this could have on smaller independent films that may rely more heavily on festivals to secure distribution. But that being said, the Film Industry Promotion law has its supporters who point out that it formally codifies films being one of China’s pillar industries, and point out that it clarifies many aspects of the film industry that were already operating, but subject to uncertainty.

Perhaps, though, uncertainty is part of what makes indie films what they are.

Indie Way of Life is a story from our issue, “Taobao Town.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.