On the trail of Chang Woo Gow, the 19th-century Chinese “giant” who traveled the world

It was the afternoon of Halloween, and I was walking into a graveyard. I was not on a hunt for ghosts or ghouls, but the burial place of a 19th-century Chinese man—albeit one of almost supernatural height.

Chang Woo Gow, or “Chang the Chinese Giant” as he became known to his audiences in the West, was over eight feet (2.4 meters) tall. He toured the world for nearly 25 years in the mid-1800s performing in front of crowds eager to see the tallest man on earth. When he retired to the southern English town of Bournemouth, he allegedly had 10-foot walls erected around his house to avoid prying eyes, and would only venture out at night to walk about town, lighting his cigar with gas lamps. It’s also here in Bournemouth, my hometown, that Chang is buried (supposedly in an enormous coffin).

Show Bill, Uffner’s mammoth giant & mite by Wellcome Collection licensed under CC BY 4.0

The life story of Chang—or Zhan Shichai (詹世钗), as he was originally called in Chinese—is difficult to piece together in part because different versions were circulated by his agents to promote his performances. At least five separate biographies of the giant were published while he was alive. Even his date and place of birth remain unclear, though it’s likely to have been sometime between 1841 and 1847 in Wuyuan, in present-day Jiangxi province.

One account suggests that Chang was born into a well-to-do family of tea planters. It’s unclear whether a medical condition caused his extraordinary height, as one account claims that Chang was not even the tallest in his family—that honor belonging to one of his sisters. Earlier biographies of Chang suggest he left home to travel on the advice of his dying father, arriving in Suzhou in 1863 just as “the Imperial army, headed by an English general” arrived to defeat Taiping rebels. Later, in Shanghai, Chang was apparently spotted by his eventual agent, Englishman James Marquis Chisholm, who persuaded him to go to Britain to perform.

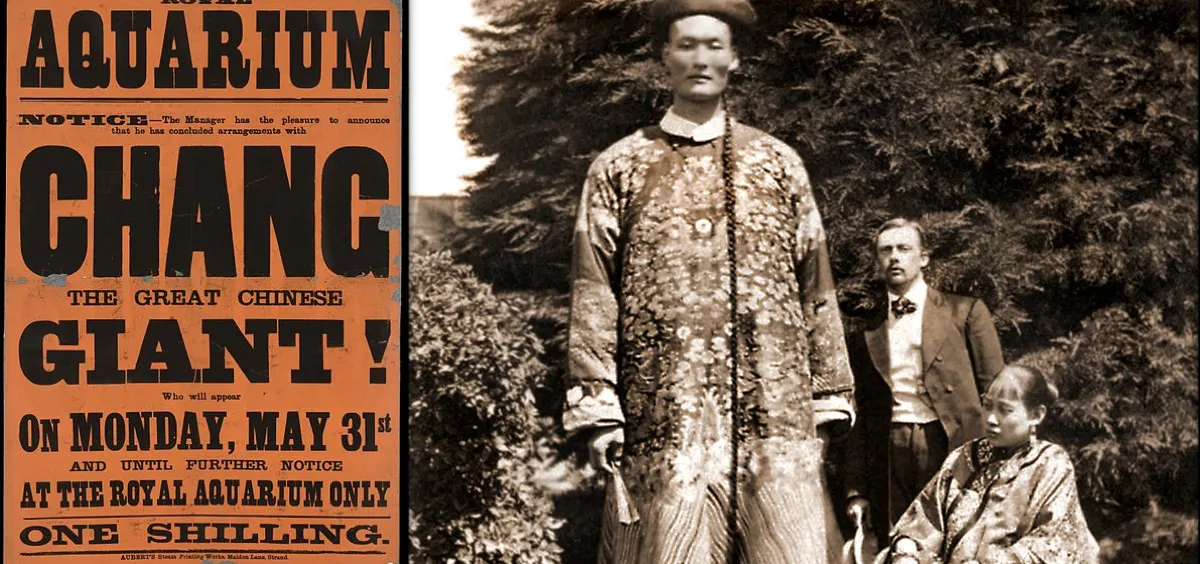

Chang first arrived in the UK in 1865, and performed at various venues in London for a typical fee of 3 shillings. One poster promoting Chang’s appearance at Piccadilly Hall proclaimed that “All giants are dwarfs compared to Colonel Chang.” He went on to perform over 600 shows in the British capital and would go on to do shows in Europe, Australia, and New Zealand. Later, Chang also went on tour in America as part of P. T. Barnum’s “Greatest Show on Earth,” reportedly earning 500 dollars a month.

Chang fascinated Western crowds due to his nationality as well as his height. He was, according to historian Sophie Couchman, promoted as both an exotic representation of the far-east “Orient,” and aggrandized as a gentleman and scholar with great intellect. In promotional photographs and in his shows, Chang was variously portrayed as sitting on a throne in “traditional” full-length imperial dragon robe, dressed as a Mongolian warrior, outfitted in in Western “gentlemanly” clothing, donning a French military uniform, or even in “full armor.”

Despite his imposing figure, Chang was described as “one of the noblest and gentlest of men” by his friends. He was also a skilled linguist, and spoke several languages fluently. His looks, too, were admired, although sometimes perhaps begrudgingly: “Judged by a Chinese standard of beauty, Chang may really be called handsome. His expression is singularly mild and gentle, almost to effeminacy. There is something very courteous and engaging, too, in his mien as he walks about from one spectator to another, shaking hands with all who desire that honour,” wrote the Sydney Morning Herald in the 1870s.

Other stories suggest Chang did not lack possible partners. In one incident, an attractive Australian woman presented him with a bouquet of flowers and asked for a kiss before giving “a worldly narrative of her prospects—rich shares in North Cross Reef—which she would place at Chang’s disposal, should he make her his bride.”

Chang turned the offer down. In fact, when the Chinese Giant first began touring, he seemed to have been accompanied by a Chinese wife, Kin Foo, though it’s possible their relationship was crafted for the show. Kin Foo disappears from the records around 1871, when Chang met and married Liverpool-born Catherine Santley in Australia. They went on to have two children, one born in Shanghai and the other in Paris.

In 1890, Chang retired and moved to Bournemouth with his family. The now world-famous performer was suffering from what was probably tuberculosis, and Bournemouth, with its sea air and pine-filled walkways, was a popular health spa in Victorian times. Chang and his wife opened up a shop selling tea and Chinese curios in their home.

The house where Chang lived is now a hotel. Though the reputed 10-foot walls are gone, the raised windows and ceilings and the extended doorways remain. An old newspaper cutting and a photo on display in the dining room also serve as reminders of the outstanding entertainer who once lived here.

A photograph on Chang on display at his former residence in Bournemouth

Chang died there in 1893, allegedly of a broken heart, just a few months after his wife had passed away. He was popular in Bournemouth and, despite the rumored wall, often invited guests into his home for tea. According to a local newspaper, “People always found him friendly and affable, and after the first novelty wore off, Chang in his appearances among the residents was always well received and attracted no special attention.”

Although Chang rarely returned to China after he gained fame, and none of his relatives attended his funeral, one can now visit what was apparently Chang’s family home in Wuyuan. A version of Chang’s story was also recorded in the Records under the Autumn Lamp on Rainy Nights (《夜雨秋灯录》), a collection of tales published in 1877. These tales depicted foreigners taking advantage of poor Chinese, whisking them away to put on exhibit in their own countries. Whether Chang’s own story was one of pure exploitation is difficult to judge, but he at least earned enough money to retire from performing and buy property before the age of 50.

Much remains unknown about Chang’s life and what became of his descendants. At some point along the way, he became a Christian, and a naturalized British citizen. He also befriended William James Day, a famous photographer. He almost certainly met the Prince of Wales, the Duke of Cambridge, and other royals and nobility, and perhaps also met Queen Victoria, Prime Minister William Gladstone, the Sultan of Turkey, Emperor William of Germany, the King of Thailand, the Emperor of Austria, and at least one Emperor of China.

Many more apocryphal stories about Chang abound, such as that he traveled round Bournemouth in a rickshaw, and that he once rode in a horse-drawn carriage that collapsed under his 26-stone frame.

In one of his last interviews before he died, Chang was quoted as saying, ”I have never cared to be shown.” That may explain why, when I finally located the spot where Chang was buried, I was disappointed to find nothing to mark the grave. Perhaps after a lifetime of being the center of attention, all Chang hoped for in death was some anonymity.

Cover Image of Poster: Royal Aquarium : … Chang, the great Chinese giant by Wellcome Collection licensed under CC BY 4.0 and Chang The Chinese Giant [c1870] Attribution Unk [RESTORED] by ralph repo licensed under CC BY 2.0