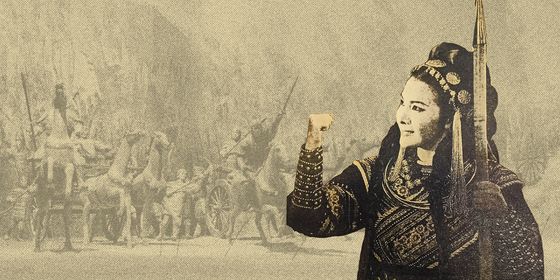

The ‘true’ tale of China’s legendary female warrior

The legend of Mulan is one of the oldest and most beloved stories in China, and many different versions of the story have appeared throughout history.

Many readers will doubtless have obsessed over the 1998 animated Disney adaptation and sung along nostalgically to the soundtrack. In the earliest adaptations, though, Mulan had no love interests and, sadly, no talking dragon named Mushu.

With the release of a live-action Disney remake of Mulan postponed amid coronavirus concerns, here are the most well-known versions of the “true” Mulan, a mythical warrior woman from the Northern Wei Dynasty (386 – 535) who spared her aging father from military conscription and served her country with distinction.

Ballad of Mulan

The first transcription of the legend of Mulan comes from the 6th century Musical Records of Old and New. Although the original text is lost to history, the story is passed on in the “Ballad of Mulan.”

In the poem, Mulan is weaving at a loom. She sighs as she thinks of the upcoming army draft that demands one male from each household. Worried for her elderly father and young brother, Mulan decides to take her father’s place and fight as a man.

Contrary to the popular Disney version, Mulan is already a polished warrior, trained in swordsmanship and martial arts. Her father and mother are proud of her abilities and allow her to serve in the army, where she distinguishes herself for 12 years before being offered riches and an official government post. Instead, Mulan humbly asks for a camel to return home to her family.

Once home, she dons women’s clothes, revealing to her befuddled comrades that she had been a woman all along.

More than a thousand years later, Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644) playwright, Xu Wei, adapted this version for the stage. Xu also gave Mulan the last name, “Hua” (花, flower), which went well with “Mulan” (木兰, magnolia). Older versions show her last name as Zhu or Wei.

Sui-Tang Romance

During the Qing dynasty (1644 – 1911), novelist Chu Renhuo popularized another, darker version of the Mulan legend. First appearing in 1695, Chu’s adaptation situates Mulan under the rule of a foreign Turkic khan at the time of the Tang dynasty’s founding, around 620 CE. In this version, the khan joins forces with the Tang emperor to unify China.

Once again, Mulan’s family is asked to provide a male soldier to fight in the war, but her father, Hua Hu, is old and has no eligible male sons to fight. Disguising herself as a man, Mulan leaves to join the main army, but is intercepted by the Xia king and his warrior daughter, Dou Xianniang.

The two warrior women are delighted to have found one another, becoming laotong, or “bonded sisters.” Things quickly turn sour, however, when the Xia king sides with the Tang’s enemy and is defeated.

Mulan and Xianniang offer up their own lives to the Tang emperor in place of the condemned army men. Moved by their act of filial piety, the emperor spares their lives.

But Mulan is still denied a happy ending. Upon returning home, she finds her beloved father dead and her mother remarried. Shortly afterwards, the khan summons her to become his concubine, and Mulan commits suicide, declaring she will only ever be loyal to her father.

Other Adaptations

In other versions of her legend, Mulan falls in love with a handsome general called Jin Yong, reminiscent of Li Shang in the 1998 Disney film. However, the couple cannot be together until Mulan stops living life as a man, which she does in a dazzling reveal that earns her the respect of the troops and spurs them to victory.

In addition to these primary versions, Mulan’s story has been reimagined countless times in film, television, opera, and literature. Adaptations range from a 1927 silent film entitled Hua Mulan Joins the Army to a bizarre comic book called “Deadpool Killustrated” in which Mulan, Sherlock Holmes, and others attempt to stop Marvel’s Deadpool from killing literary characters.

In all the adaptations, Mulan is driven by her devotion to family and country, traits which have made her a popular motif in art and literature. However, her story can also be read as an early critique of traditional gender roles. In the “Ballad of Mulan,” she is trained in the “feminine” art of weaving, but she also lives life as a male soldier for 12 years, and no one could tell the difference. The ballad ends Mulan’s story provocatively with the following two couplets, painting a thin line between male and female:

For the male hare has a lilting, lolloping gait,

And the female hare has a wild and roving eye;

But set them both scampering side by side,

And who so wise could tell you “This is he”?