The most powerful man never to be emperor of the Qing dynasty

With a name that sounds like it came straight from a late night in the writers’ room for The Mandalorian, and a backstory that has inspired both romance novels and epic tales of martial valor, the Manchu prince Dorgon is perhaps one of the most intriguing figures in Qing history despite—and this was something of a sore point—never becoming emperor.

Dorgon was instrumental in the Manchu conquest of China and was the most powerful man in the empire for over a decade. Yet his life was cut short in its prime. On December 31, 1650, Dorgon died (possibly murdered) while on a hunting trip near present-day Chengde in Hebei province. He was only 38 years old, and his death caused a smoldering political feud to ignite into a hotly contested struggle for power within the Qing imperial clan.

His father was Nurhaci, a chieftain who in the early 17th century unified disparate clans living in the mountains and forests of what is today northeastern China into a powerful confederation. Nurhaci used his military skills and political savvy to give his confederation an identity, drawing on the history of the Jurchen, another group from the same region that had established the Jin Empire and conquered much of northern China in the 12th century.

Dorgon was the 14th of Nurhaci’s sons, and there is evidence that he was one of his father’s favorites. However, growing up as one of the youngest brothers in a ruling clan was far from easy. Dorgon’s mother had become Nurhaci’s primary consort following the death of the previous empress. In addition to Dorgon, she also gave birth to Nurhaci’s 12th son, Ajige, and his 15th son, Dodo.

After Nurhaci died, control of the new confederation fell to a council dominated by Dorgon’s older brothers, especially Hong Taiji. According to palace legends, Hong Taiji saw his younger half-brothers and their mother as a political threat. Dorgon’s mother was either murdered or forced to commit suicide in 1626. Hong Taiji built on his father’s legacy and established a new state, the Great Qing, and his confederation became known as the Manchus.

After a failed bid for the throne after Hong Taiji’s death, Dorgon became the regent of Hong Taiji’s 6-year-old son (Wikimedia Commons)

Hong Taiji died in 1643, a year before the Manchus allied with the Ming dynasty general Wu Sangui and began their conquest of China. It was Dorgon, now acting as regent on behalf of Hong Taiji’s young son and heir, who led the Manchus through the Shanhaiguan Pass into China, defeated the rebel armies of Li Zicheng in the former Ming capital at Beijing, and moved the capital of the Great Qing there in 1644.

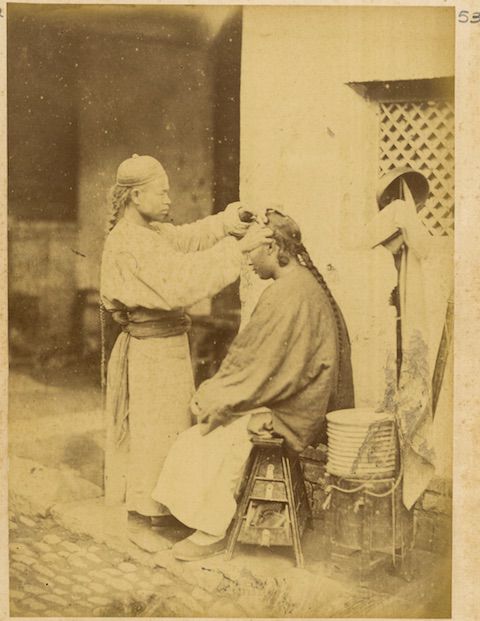

Dorgon and his brothers then consolidated Qing rule throughout the country, ordering all Chinese males to shave the fronts of their heads and braid the remaining hair into a long queue in the Manchu fashion as a sign of submission to the new rulers. At the same time, Dorgon established an important precedent by supporting and sustaining many of the institutions and rituals of the Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644). This hybrid system of grafting Inner Asian military and political traditions onto Chinese dynastic system would become one of the cornerstones of the Qing empire, which would soon expand to include large swaths of Central Asia, the Mongolian steppe, and the island of Taiwan.

Meanwhile, Dorgon strengthened his power at court. He had a close ally in the Empress Xiaozhuang, the mother of the young Shunzhi Emperor. Despite being the consort of Dorgon’s older brother, Hong Taiji, Empress Xiaozhuang was much closer in age to Dorgon. Their shared interests, mainly when it came to the reign of the young emperor, inevitably led to whispers of a more intimate relationship between Dorgon and the young widow, and even rumors of a secret marriage.

Secretly wed or not, Dorgon was able to use his position at court to amass power, and his reputation as a “quasi-emperor” invited the enmity and jealousy of other imperial family members. Dorgon exempted himself from the ritual kowtow in the presence of his nephew, the emperor, while his harsh treatment of those who challenged his authority strained relations with his other brothers.

Dorgon demoted his half-brother Jirgalang from the position of assistant regent, and in Jirgalang’s place, promoted his full brother Dodo, a key political ally. In her historical novel The Green Phoenix, author Alice Poon speculates that Dorgon’s difficulties as a young man, when he had been at the mercy of his domineering older siblings, gave him a “cruel and distrustful streak, rooted in the grievous loss of his mother to political murder in his early teens,” which affected his relationships with those closest to him.

When Dorgon died in 1650, he was at the peak of his power, but his death allowed Jirgalang and Nurhaci’s other living sons to move against Dorgon’s allies at court. Dodo had died in 1649, but Dorgon’s other full brother Ajige died in prison in 1651. On March 12, 1651, the court issued a decree in the name of the still-adolescent Shunzhi Emperor accusing Dorgon of usurping power and altering official documents. The edict further stripped Dorgon of his titles, and even allegedly ordered Dorgon’s body exhumed and posthumously flogged for crimes against the throne.

Official genealogies state that Dorgon did not have any sons to inherit his titles. Instead, he named his nephew Dorbo as his heir. The 1651 decree stripped Dorbo of this inheritance and rescinded Dorbo’s adoption by Dorgon. Without an heir, Dorgon’s tomb went untended for many generations.

It wasn’t until 1774, during the reign of the Shunzhi Emperor’s great-grandson, the Qianlong Emperor, that Dorgon was officially reinstated in the imperial clan’s genealogy. Dorgon’s title, the Prince of Rui, which had remained vacant since his death, was then bestowed to a great-great-grandson of Dorbo. The title would be passed down by Dorbo’s descendants until the artist Aisin-Gioro Yinian, also known as Rushiguan Ge and Jin Jishui. After his uncle's death, Jin refused to accept the title as he was angry with the last Qing emperor Puyi, who collaborated with the Japanese during World War II.

In the 20th century, many Chinese protested against Qing rule by shaving off their queues (Wikimedia Commons)

“Dorgon probably goes down in history as the valiant Manchu conqueror who put the decaying Ming dynasty out of its misery,” writes Alice Poon. The prince regent died young, but left a lasting legacy. The Manchu hairstyle—the queue—would be worn into the 20th century.

He was also a steady (if sometimes overbearing) presence in the court of very young emperor during a time of change and transition for the country. When Dorgon’s name was finally restored to the imperial lineage over a century after his death, the Qianlong Emperor eulogized how instrumental Dorgon had been in the early years of Qing rule. He was never an emperor, perhaps, but few emperors could rival Dorgon for his contributions to the success of the Qing dynasty.

Cover image from VCG