Historian Tonio Andrade recalls a mostly forgotten moment of 18th century Chinese diplomacy and winter sports history

The 2022 Winter Olympic Games are not the first time the city of Beijing has seen international teams competing for glory in winter sports. Over 200 years ago, a most unusual skating party took place on a frozen lake in the heart of the capital, with flying arrows, crashing skaters, and two countries competing for national pride on the ice.

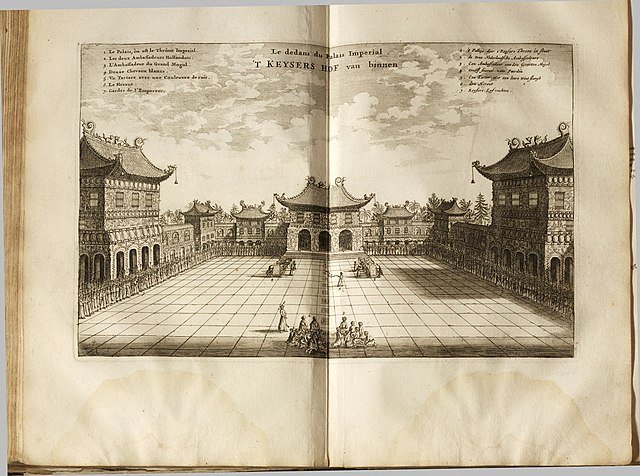

It was the winter of 1794 - 1795, and the aged Qianlong Emperor was celebrating 60 years on the throne. It was a huge deal. The court invited guests from all over the known world. Manchu nobles, Chinese officials, Mongolian chieftains, and Tibetan lamas mingled with Vietnamese envoys and Korean diplomats at parties, receptions, and banquets. While the emperor was the star attraction, most of the conversation focused on a group of unusually attired and coiffed visitors from beyond the seas: The Dutch East India Company had sent a delegation to China, led by Isaac Titsingh, to congratulate the emperor on the longevity of his rule.

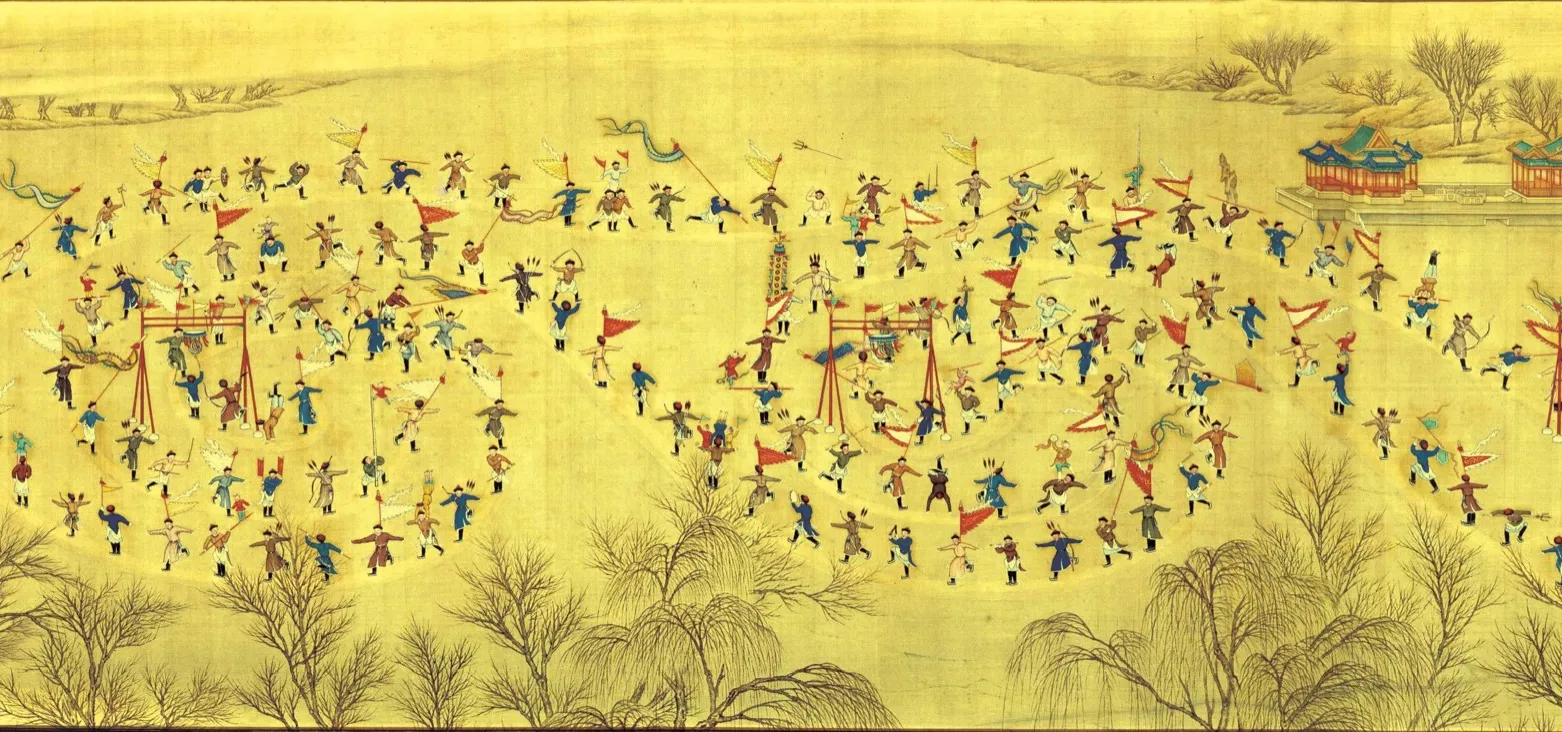

On a cold January day in 1795, the Qing court and guests turned out to celebrate with winter sports in the imperial Western Gardens. From cold seats in wooden sleighs, the emperor and his guests watched as Qing imperial troops sped across the ice on skates bound to their feet with ribbons and cords. The emperor was quite fond of the “ice games,” or bingxi (冰嬉). In one of his many poems, the Qianlong Emperor once described the reflection of imperial skaters on the smooth frozen surface as looking like “phoenixes flying across the sky.”

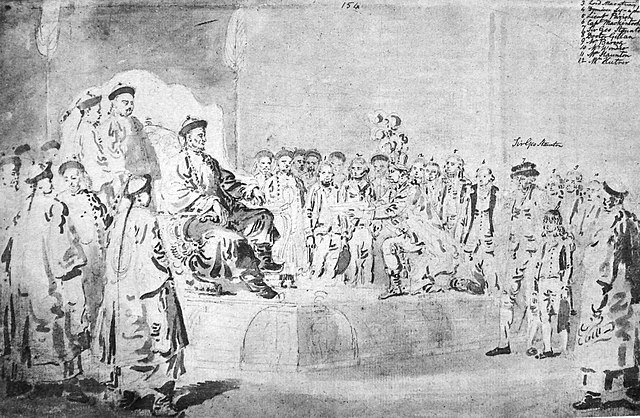

The emperor turned to Titsingh and asked if the ambassador would like to join in the fun. Titsingh, nearly three decades removed from his last outing on ice, demurred. Still, some of the younger members of the delegation were excited about the chance to show these Manchus a trick or two. Servants hurried back to the delegations’ quarters to fetch skates. The Dutch had come to Beijing prepared. It was probably a good thing, as the Manchu skates differed from the European design both in their bindings and blades, which were shorter and ended abruptly at a right angle, rather than curving upward as most skates do today.

While the imperial skaters were graceful and impressive in motion, the method of stopping was a bit startling to the Europeans. “These Chinese, unable to check their rapidity, let themselves fall upon the ice as soon as they came close up to the sled, in order that they might not run over the Emperor,” recounted businessman Andreas Everardus van Braam Houckgeest.

As the Europeans took to the ice, a crowd of imperial officials and other guests gathered to watch the Dutch spin and speed around the lake as the emperor finished his breakfast. Then, as the emperor signaled that he was ready for the games to begin, the Dutch skaters returned to their seats in the audience and let the professionals take the ice.

With a loud explosion marking the beginning of the performance, the imperial skaters whizzed past the gallery, racing the length of the ice, twirling and leaping, demonstrating their martial prowess by firing arrows at targets with carefully placed shots while skating at full speed—a sport known as “Follow the Dragon Trail and Shoot (龙传射球).” Another game, “ice football (冰上蹴球),” involved two teams on skates slamming and tackling their opponents to win control of a white leather ball. The winners were rewarded with gifts and treats from the emperor.

Why “speed skate archery” and “ice rugby” have not become Winter Olympic sports is as much an IOC mystery as the color of Eileen Gu’s passport.

The scene of young Dutch and Manchu skaters trying to one-up the other on a Beijing lake is just one of many vignettes from historian Tonio Andrade’s book, The Last Embassy: The Dutch Mission of 1795 and the Forgotten History of Western Encounters with China, published last year by Princeton University Press. Andrade argues the story of Titsingh’s delegation and their visit to the Qing court, including this bit of winter sports history, have been mostly forgotten or unfairly dismissed as a failure by historians today.

This is due, in large part, to the long shadow of the Macartney Mission. Three years earlier, this British delegation sent by King George III had failed to harangue the Qianlong Emperor to open his markets and adjust trade policy to make it easier for international merchants to profit in the China trade. The effort famously ended with Macartney’s bluster being repaid by a polite reminder from the Qianlong Emperor that the Qing Empire had all the trade goods it required. Macartney’s requests were deemed unreasonable.

The Dutch took a different approach than their British predecessors, opting for a more conciliatory strategy. Contemporary accounts, especially those published in Britain, mocked the Dutch for getting no further than Macartney had despite continually acquiescing to Qing ritual protocol, even enduring the “humiliation” of kowtowing. Continental appeasement and placation were judged against British backbone and found wanting. Pundits at the time believed that any form of conciliation on the part of one side only fed the arrogance of the other, a formulation not unfamiliar to those following the rhetoric from politicians on both sides of the current war of words between China and the United States.

Later historians folded many of the same assumptions into the paradigm of a “tributary system” that inevitably clashed with an emerging—and implicitly more modern—international order. Andrade is one of many historians who has recently attempted to complicate this narrative. He argues that the Dutch mission demonstrated there were alternatives to confrontation, and that Ambassador Titsingh and his superiors from the Dutch East India Company had a more sophisticated view of the politics of Asian empire. The Dutch mission was one of congratulation rather than negotiation. They were to be guests at a party: building goodwill, developing relationships, and discussing business only if the opportunity arose. Judged in this way, the assignment was not a failure.

In addition to adding to the more nuanced understanding of Qing guest rituals described in earlier studies by James Hevia, Henrietta Harrison, and other scholars, The Last Embassy also is a highly readable account of what it was like for a European traveler in 18th century China. Andrade presents a detailed, nearly day-by-day report of the delegation’s adventures and mishaps on and off the ice, giving a sense of immediacy by writing in the present tense used by historians of a certain generation when filming talking-head commentary for serious documentaries.

The 1795 Ice Games were not the only time the delegation enjoyed skating in the northern Chinese winter. Skating on the canals and ponds around the capital had become a popular way for the younger and more energetic foreign delegates to pass the time waiting for the imperial court to receive them. The sight of the foreigners with their strange dress and hair zipping across the ice drew large crowds of onlookers. Not all sessions on the ice ended well: A skating party on Christmas Day, 1794, ended abruptly when one of the Dutch skaters fell through the ice and needed to be rescued.

These all-too-human moments of competition, amusement, and the occasional dunking of a Dutchman, restore the element of connection and personal choice that suggest the model of clashing civilizations assumed by many Chinese and Western writers even today was not inevitable. There was—and continues to be—space between the misunderstandings and missteps for moments of communication, conciliation, and even skating parties.