From marking good looks to advancing political careers: See how the rules and styles of facial hair changed in ancient Chinese history

Picture a random man from China in your mind: Does he have a beard or mustache?

If your answer is no, chances are that it’s a man living in modern China. A clean-shaven look has been the mainstream since the start of the 20th century, but in ancient China, almost all the adult men—except eunuchs—kept facial hair. A luxuriant beard used to be an important standard for judging handsome men.

In modern Chinese, beards, mustaches, and whiskers all can be called 胡须 (húxū) or 胡子 (húzi). But in ancient times, hair that grew on different parts of the face had different names: It was called called 髭 (zī) when it grew from the upper lip, 髯 (rán) when it grew on the side of the face, and a beard on the chin was known as 须 (xū).

Historical texts included many descriptions of men’s appearances that focused on their beard, often as proof of their good looks. In “Moshangsang (《陌上桑》),” a folk-style poem created in the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220), heroine Lu Fu praised her own husband for being good-looking, saying “He has a fair complexion and long beard (为人洁白皙,鬑鬑颇有须).”

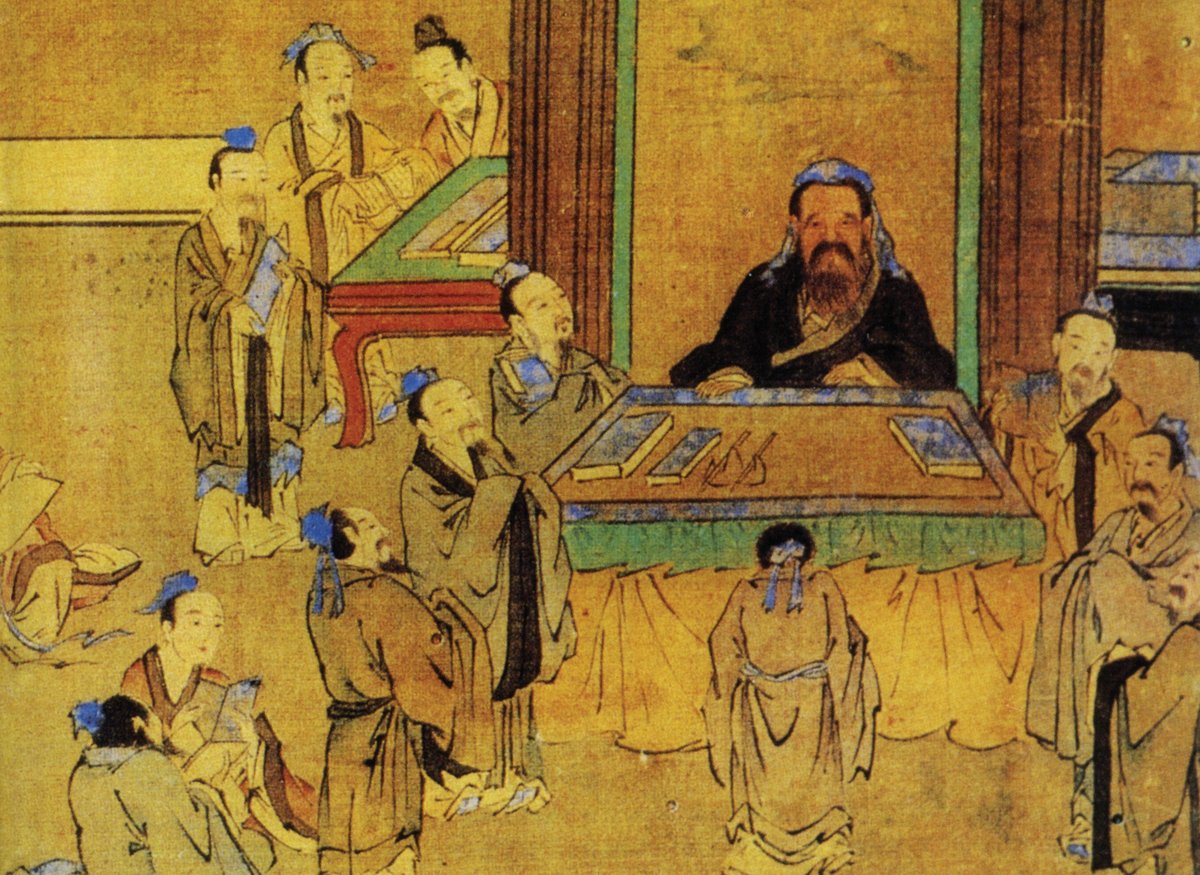

In the Records of the Three Kingdoms (《三国志》), a historical record created by Jin dynasty (265 – 420) historian Chen Shou (陈寿), scholar Cui Yan (崔琰) was described as having “a four-chi beard and a dignified appearance (须长四尺,甚有威重),” earning him the stellar reputation of a man in possession of a beautiful beard (chi was a unit of length that changed definition depending on the time period, but was roughly equal to 20 to 30 centimeter).

The most famous beard-owner in Chinese history is likely Guan Yu (关羽), the legendary military general of the Three Kingdoms era (220 – 280) known as the “Martial Saint (武圣).” One of Guan’s other nicknames was “Beautiful Bearded Gentleman (美髯公),” because he had a two-chi-long beard. Thanks to the classic novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms (《三国演义》) and many subsequent adaptions of it, almost every Chinese person is familiar with Guan’s hirsute image. In the book, warlord Cao Cao (曹操) even sent Guan a yarn covering, known as a rannang (髯囊), to protect his long beard with.

However, the title “beautiful bearded gentleman” was not enjoyed by Guan exclusively. It was shared by many historical figures, including poet Su Shi (苏轼) and calligrapher Cai Xiang (蔡襄), both of the Song dynasty (960 – 1279), and Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644) politician Zhang Juzheng (张居正).

In Chinese medicine, it was believed a long beard is a reflection of energy and strength. In Miraculous Pivot (《灵枢》), a medical text believed to be written in the Warring States period (475 – 221 BCE), it is mentioned that: “If a man has abundant blood and qi [two of the body’s five vital substances in traditional Chinese medicine], he will have a beautiful long beard; if he lacks blood but has ample qi, his beard will be short; if he has enough blood but lacks qi, his beard will be sparse; if he lacks both blood and qi, he will be beardless (血气盛则髯美长, 血少气多则髯短,故气少血多则髯少,血气皆少则无髯).”

Ancient Chinese were not quick to shave their beard, for as Confucius once said: “Our body, hair, and skin are given by our parents and we shouldn’t damage them lightly. That is the first step of filial piety (身体发肤受之父母,不敢毁伤,孝之始也).” In the Qin dynasty (221 – 206 BCE), forcibly shaving off a man’s beard was even administered as a penalty for minor crimes, a practice known as 耐刑.

The longest beard in Chinese history might have belonged to Xie Lingyun (谢灵运), a famous poet born in the Eastern Jin dynasty (317 – 420). According to the Five Assorted Offerings (《五杂俎》), an essay collection created by scholar Xie Zhaozhe (谢肇淛) in the Ming dynasty, “Xie’s beard was so long it approached the ground (谢灵运须垂至地).” According to the Records of Strange Events (《独异志》), a short story collection by Li Kang (李亢) of the Tang dynasty (618 – 907), before Xie was executed for treason, he cut off his long beard and donated it to the Qihuan Temple in Guangzhou. Later, his beard was used to decorate a bearded statue of the bodhisattva Vimalakirti, and kept until the Tang era.

Sometimes, a man’s beard could even influence his career. According to Qing dynasty (1616 – 1911) scholar Hong Liangji’s (洪亮吉) Notes on Poets and Poetry (《北江诗话》), when Xu Zhigao (徐知诰), a government official, was appointed as the prime minister of the Southern Wu state in the 10th century, he took medicine to whiten his beard and hair. Xu had feared his dense black beard would make him look too youthful in the eyes of his colleagues and the public. Later, in the Song dynasty, famous official Kou Zhun (寇准) did the same thing before he became the prime minister.

There was another widely known story about Kou’s beard, which even birthed an idiom that is still used today. According to the History of Song (《宋史》), once Kou was having dinner together with vice prime minister Ding Wei (丁谓), an infamous treacherous official, and Kou accidentally got soup on his long beard. In order to please Kou, Ding immediately stood up and wiped the soup away with his own sleeve. But Kou wasn’t amused, seeing through Ding’s attempts to flatter him. So Kou asked sarcastically: “Is an official dealing in government affairs supposed to wipe the beard of his superior? (参政国之大臣,乃为官长拂须邪?)” Since then, the term 溜须 (liū xū, wiping the beard) has been used roughly in the same way as the English idiom “to lick someone’s boots.”