How ancient Chinese battled moths, mold, and moisture to keep their manuscripts safe

According to the National Bureau of Statistics, China has published 11 billion books in 2021. That’s nearly eight new books for every Chinese citizen. In ancient times, however, books were far more exclusive, reserved for the small proportion of the population who were literate and could afford them.

In fact, one curious netizen has done the math: During the Northern Song dynasty (960 – 1127), when merchants were beginning to flourish and book prices were relatively low, the official price for one volume of a book was 100 wen (1 wen was roughly 0.7 yuan today). The Confucian classic Mencius (《孟子》), a philosophical text of 14 volumes read nationwide, would have cost 1,400 wen, approximately 980 yuan today.

Since books were so valuable, and took so much effort to produce before the advent of modern printing techniques, they had to last a long time. But before paper, protecting written works from mold, moths, and disease required a host of innovative maintenance methods.

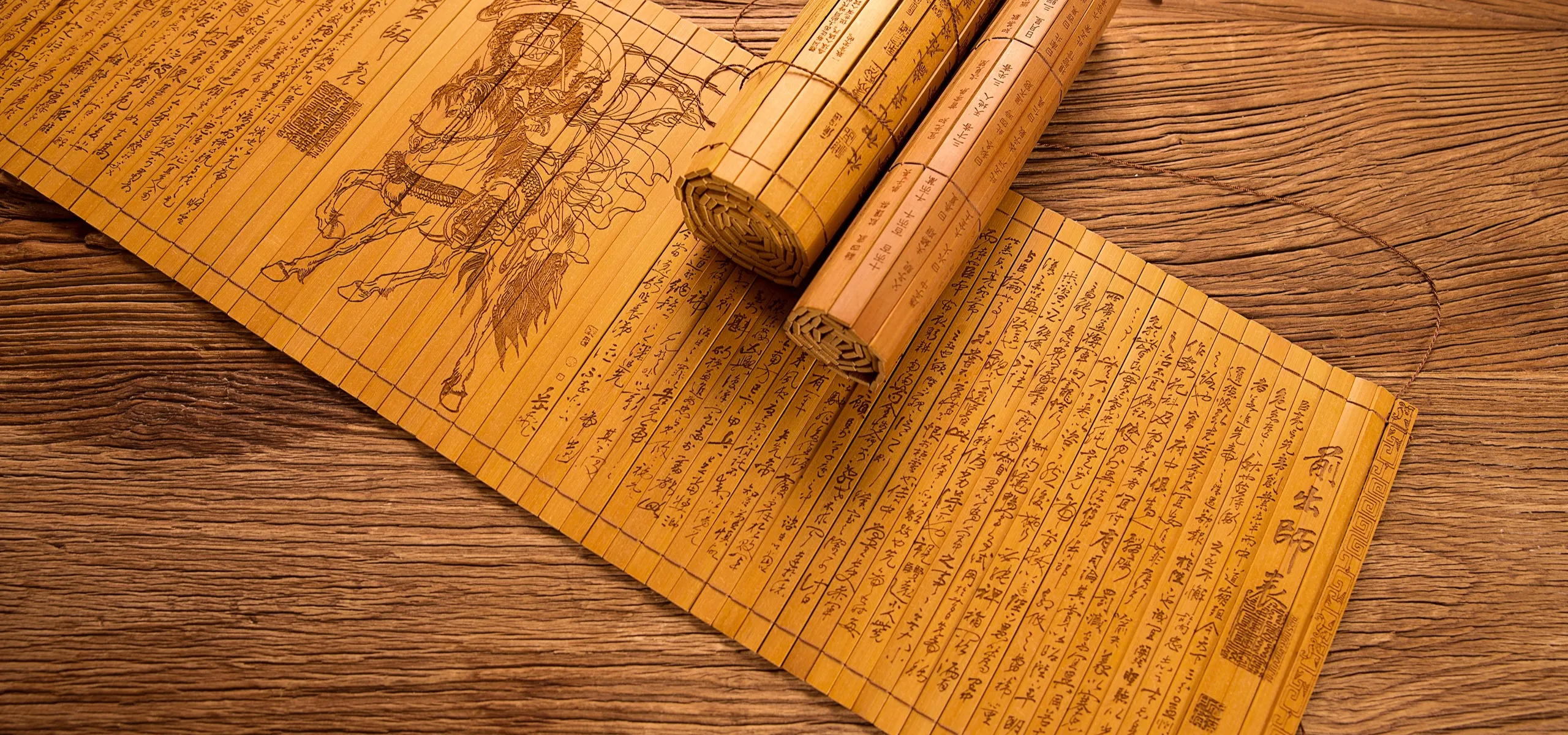

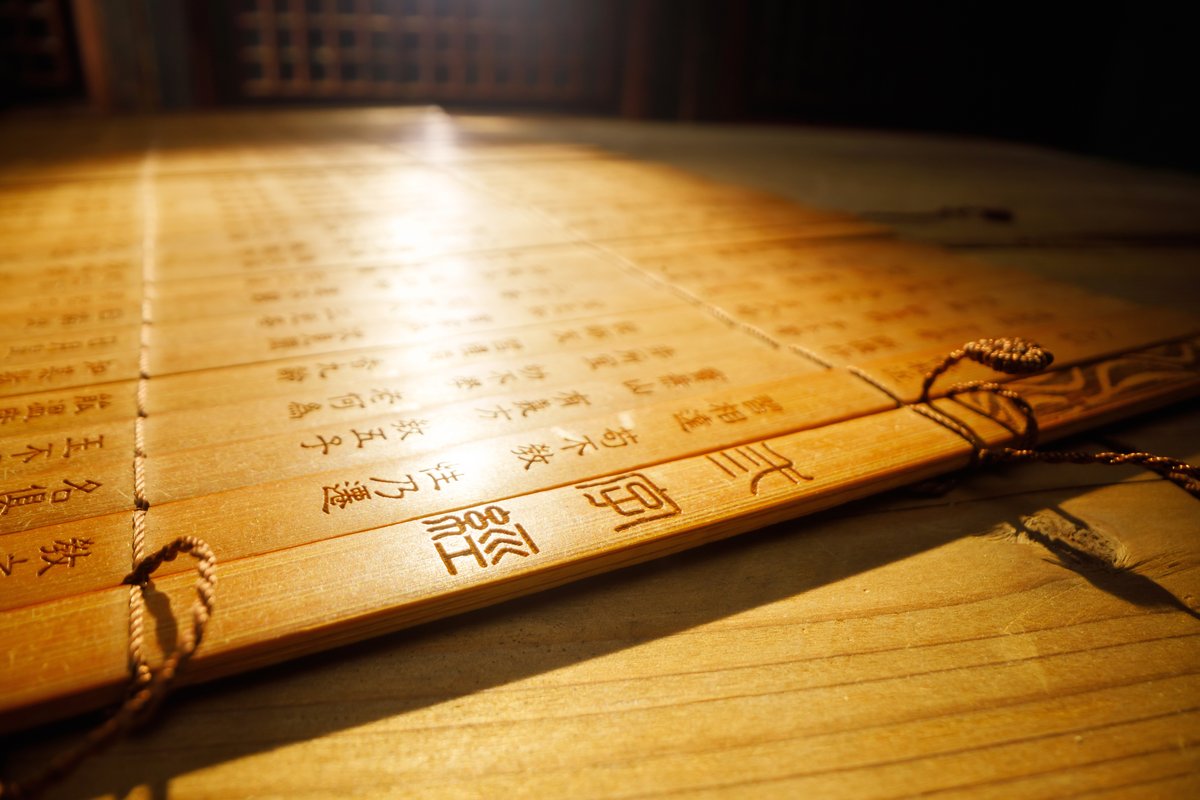

Prior to the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE), when eunuch Cai Lun (蔡伦) improved paper-making technology and promoted it across the empire, books were mostly written in ink upon rows of bamboo slips. Though the bamboo was firm and durable, it required protection from moisture and parasites.

Protecting bamboo-strip books involved 杀青 (shāqīng, literally “kill the green”) a procedure that involved drying the bamboo strips before writing on them. Han-dynasty scholar Liu Xiang (刘向) recorded the practice in his encyclopedia The Subject Catalog (《别录》): “Since the fresh bamboo contains moisture, it is easily eroded or eaten by worms. Anyone who makes writing slips of bamboo should dry them on the fire first.” The term 杀青 is now used to refer to the completion of a book manuscript.

Another legacy of writing on bamboo may have been the convention of illustrating book covers. Authors normally wrote the title of their work and the name of the chapters on the reverse side of the bamboo strips, so that when they were rolled up people would know the name of the piece. These two strips containing the title of the work and the name of the first chapter were known as 赘简 (zhuìjiǎn, extra bamboo strips), and they are often referred to as the first book “covers.”

After the Han dynasty, as paper-making technology became more widespread, printers had another menace to avoid: moths. To moth-proof a work, one popular approach was dyeing paper in a traditional Chinese medicine made of golden cypress bark before drying it for writing. The mixture contained alkaloids that could destroy insect eggs. This method was called 染黄 (rǎn huáng, dye in golden cypress) and would turn the paper a yellowish color, giving it the name 黄纸 (huáng zhǐ, yellow paper).

This ranhuang technique spread during the Northern and Southern dynasties (420 – 589), until the official court took up the procedure for official documents in the Song dynasty (960 – 1279). According to the Song Dynasty Manuscript Compendium (《宋会要辑稿》), a historical text recording Song history, many books made of regular paper collected in the official libraries had been ravaged by worms and other insects, so the Song government ordered them re-published using yellow paper.

In the Southern Song dynasty, people also invented “pepper paper,” made by soaking paper in pepper-infused water, which became popular since the smell of pepper could also ward off insects. The technique appears to have been effective: a large collection of books made with pepper paper belonging to Qing dynasty (1616 – 1911) collector Ye Dehui (叶德辉) remains undisturbed by pests even today.

Herbs could also help to preserve manuscripts. According to Dream Pool Essays (《梦溪笔谈》), an encyclopedia written by Song-dynasty scholar Shen Kuo, “people in ancient times put citronella grass [芸香草 yúnxiāngcǎo] inside books to protect them from being eaten by worms.” In fact, officials responsible for collating books and records were often know as “Yunxiang Officers (芸香吏)” after the plant.

Another important tradition was simply airing books under the sun to prevent accumulation of dust and mold, a practice which dates back to the Zhou dynasty (1046 – 256 BCE). By the Tang (618 – 907) and Song dynasties, it had become common practice. Tang herbalist Chen Cangqi (陈藏器) stated in his medical book Supplement to Materia Medica (《本草拾遗》) that “In regions south of the Yangtze and Huai rivers...after Minor Heat, the 11th solar term of the year, everyone should air their books under the sun.”

Qing-dynasty (1616 – 1911) scholar and book collector Liang Dingfen (梁鼎芬) valued the practice of airing books so much, that he designated four long desks on every floor of the library at the Fenghu Academy to book airing. In his essay “Four Provisions for the Library (《丰湖书藏四约》),” Liang stated that when airing a book, it should be flipped so that both the front and the back could be dried. The books would get rather warm, so the librarian should wait for them to cool down before storing them again.

Airing one’s books could also be used euphemistically. In the Qing dynasty, the scholar Zhu Yizun (朱彝尊) is said to have once laid down on a street with his stomach exposed, claiming he was “airing his books.” The joke referred to a Chinese idiom that describes an intelligent person as having a bellyful of books. Zhu’s behavior even attracted the attention of Emperor Kangxi, who later hired him to take charge of compiling the empire’s official history books.

Of course, book lovers can be rather obsessive about caring for their tomes. Xu Shidong (徐时栋), a book collector of the Qing dynasty, went to great lengths to protect the 60,000 works he had collected in his private library in Ningbo, Zhejiang province. He released a list of rules to protect his books: “Don’t twist the spine; Don’t bend the corners; Don’t use your saliva to help turn the pages; Don’t rip it; Don’t put other paper inside it; Don’t store it in bad taste; Don’t alter it lightly; Don’t show it to vulgar people; Don’t lend it for too long.” Sound advice even in today’s market of mass produced books.