China’s Lunar New Year celebrations begin with rituals and offerings to the kitchen god

It’s a week before the Lunar New Year holiday officially begins, but festivities and rituals are already underway. On the 23rd (or 24th for some places) day of the twelfth lunar month, households around the country honor Zaoshen, the kitchen god or the hearth god (灶神), in anticipation of New Year holiday around the corner. This celebration is known as Xiaonian (小年), Little New Year.

The kitchen god is believed to have been sent by the Jade Emperor, the supreme ruler of heaven and earth, to watch over the human world. He lives in the kitchen of every family and records their good and bad deeds throughout the year. At Little New Year, he returns to heaven to report to the Jade Emperor, who then rewards or punishes the family accordingly.

To ensure a favorable report, people prepare sweet offerings such as melons and guandong candy, a sticky treat made of glutinous millet and sprouted wheat, and even smear honey on the mouth of the god’s portrait. The idea is that after receiving these treats, the kitchen god will only speak well of the family before the Jade Emperor, or if not, the honey may seal his lips.

Families light incense and place candies and yellow rice cakes in front of their portrait of the kitchen god. Then they may kneel and pray, holding a rooster in hand, a more convenient symbol of the horse on which the deity rides to heaven.

As the incense burns, the old portrait is taken down and burned, which signifies sending the god to heaven, along with printed couplets expressing good wishes for his heavenly journey. Straw and grain are added to the fire to feed his mount. The ceremony concludes on the last day of the lunar calendar when people welcome the kitchen god’s return to the earthly realm with joy.

This ritual has ancient origins. According to Comprehensive Discussions in the White Tiger Hall (《白虎通》) , a collection of court intellectual debates on society, politics, and philosophy compiled in the first century, it can be traced back to the “Five Sacrifices” of the Western Zhou dynasty (1046 – 771 BCE), which honored the five gods of “gate, door, well, stove, and central chamber” who were collectively responsible for the safety of a family. In the Analects, Confucius was asked to explain a popular saying at that time which went “Instead of flattering the (lofty) god Aoshen, why not flatter Zaoshen?”, suggesting the kitchen god was at least widely known well before the Common Era.

Over the centuries, the kitchen god has taken on various personas. According to an ancient anonymous Daoist text Heavenly Lord of Spiritual Treasures’ Supplement to the Hearth God Sutra (《太上灵宝补谢灶王经》), the kitchen god was once identified as a female deity called the Mother of Fire, who “lived alone on Mount Kunlun” and could “communicate with the heavenly realm, control the five elements, and reach the divine.”

However, during the Eastern Han period (25 – 220), the deity became male. The reason, according to Wang Jinglin, former lecturer at the Central Academy of Drama, is that as society transitioned from ancient matriarchal culture to a patriarchal one, men became the primary breadwinners and were associated with food, thus, the divine being began to be seen as male. In the Song dynasty (960 – 1279), only men were allowed to offer sacrifices to the kitchen as women (who took on most of the cooking duties) may have spilled food cooking during the year. The women’s presence might remind the deity of the misconduct and report the waste to the Jade Emperor.

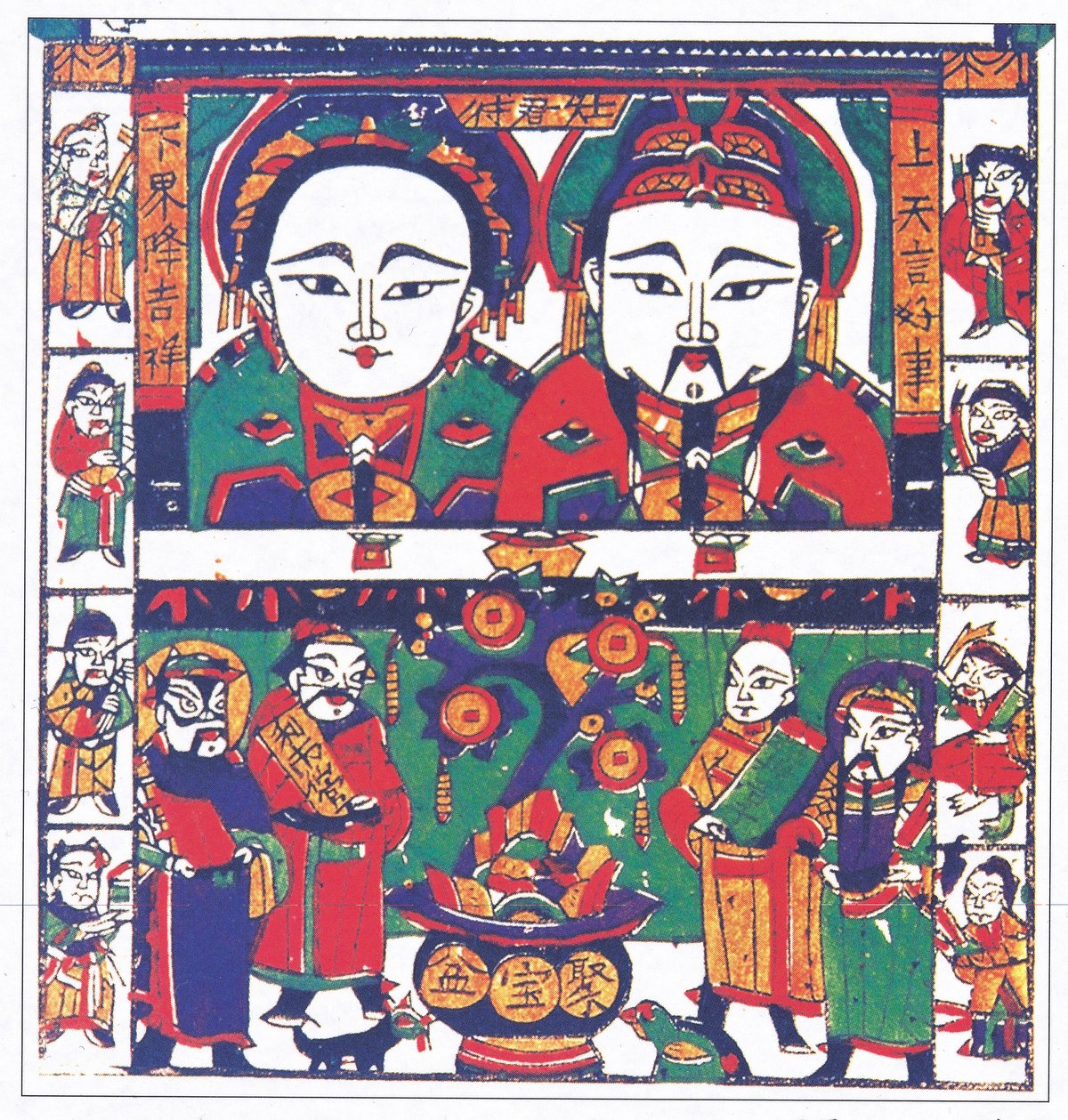

Later, the kitchen god was depicted with a wife: Grandma Kitchen. Today, both single (male) and couple portraits of the deity are commonly found throughout China.

In addition to appearance, the power attributed to the kitchen god gradually evolved beyond the practicality of providing food, expanding to the ability to determine a family’s prosperity and later even how long they can live. A fourth-century compilation of legends In Search of the Supernatural (《搜神记》) tells the story of Yin Zifang, a generous and filial person from the central province of Henan during Emperor Xuan’s reign (74 – 49 BCE). One day, while Yin was making breakfast, the kitchen god appeared to him. Yin immediately kneeled and kowtowed in admiration, offering a yellow goat in sacrifice to the deity. As a reward, he gained enormous wealth and his family was blessed for generations to come, prompting locals to follow suit in the worship of the god. Later in the fourth century, the kitchen god gained even more power and became known as a celestial being sent by the Jade Emperor to monitor human actions.

The Inner Chapters of Baopuzi (《抱朴子·内篇》), a Daoist canon written in 317, describes a heavenly bureaucracy in which the deity carefully recorded the sins of individuals for the Jade Emperor, who reduces the lifespan of those who committed minor offenses by three days and more serious offenders by 300 days. People’s uneasiness about the heavenly retribution no doubt strengthened the fear of the kitchen god.

The dates on which the kitchen God was worshipped also varied. The first documented official worship took place in the Western Zhou dynasty and was performed by high-ranking officials. It was not until the Western Han dynasty (206 BCE – 25 CE) that the emperor himself began to engage in the worship seriously, due to the god’s increasing prominence in folk beliefs. Over time, the ritual changed from multiple minor celebrations in summer and winter to a single grand ceremony before the Lunar New Year. Proceedings of Government in the Different Months (《礼记·月令》), a Confucius ritual text written in the Han dynasty, documents traditions before the unification of China in 221 BCE of offering millet and animal organs to the kitchen god at the beginning of summer.

In the Song dynasty, the worship of Zaoshen became a well-established wintertime tradition. A rhyme of the time went, “On the day of the Little New Year, the festive season is here. Girls wear flowers, boys light crackers. Wives don flower jackets, husbands chuckle with laughter.”

In the Qing dynasty (1616 – 1911), the dates for the celebration were prescribed based on one’s status, as illustrated by the saying “officials third, civilians fourth, boatmen fifth”. That is, royalty and government officials celebrated the occasion on the 23rd of the 12th lunar month, ordinary people on the 24th, and the lowly boat people who lived mainly in the southern provinces of Fujian and Guangdong on the 25th. However, in imitation of royal worship, civilians in northern China gradually brought forward the Little New Year to the 23rd after the Daoguang era (1821 – 1850).

The reverberations can be felt today, in the widespread yet inaccurate perception that people in northern China celebrate Xiaonian on the 23rd while those in the south do it on the 24th. According to a 2012 study by Li Xianhong, a PhD candidate in history at Peking University, however, the dates for the worship are more or less arbitrarily split on the two dates in both northern and southern China. Similarly, it is difficult to generalize about a standard practice in customs based on the North-South divide. For example, while many northerners eat dumplings on this day to wish for the kitchen god’s successful departure, people in parts of Shanxi province in northern China typically have stir-fried corn mixed with sugar, another reminder for the god to sweeten his language. While in Guangxi, locals would make fried rice cake as a symbol of their wish for reunion.

Even more variety comes from non-Han celebrations of Little New Year. Ethnic Mongolians, who live mainly in the northern regions of China, often light a fire with dry cow dung in their yurts and offer the best parts of lamb, liquor, butter, and other delicacies to the deity. They also decorate their doors with reeds and tie colorful ribbons to the stove. The ribbons in blue, white, yellow, red, and green symbolize the sky, clouds, Buddhism, fire, and life respectively, bringing the god’s blessings on the family and livestock.

But while rituals and beliefs may vary across peoples, the overarching theme of Little New Year remains constant: a request for divine favor to provide sustenance, prosperity, and protection for the new year.