In China’s changing countryside, young farmers and local officials are embracing AI to tackle conundrums from the aging population to pest control

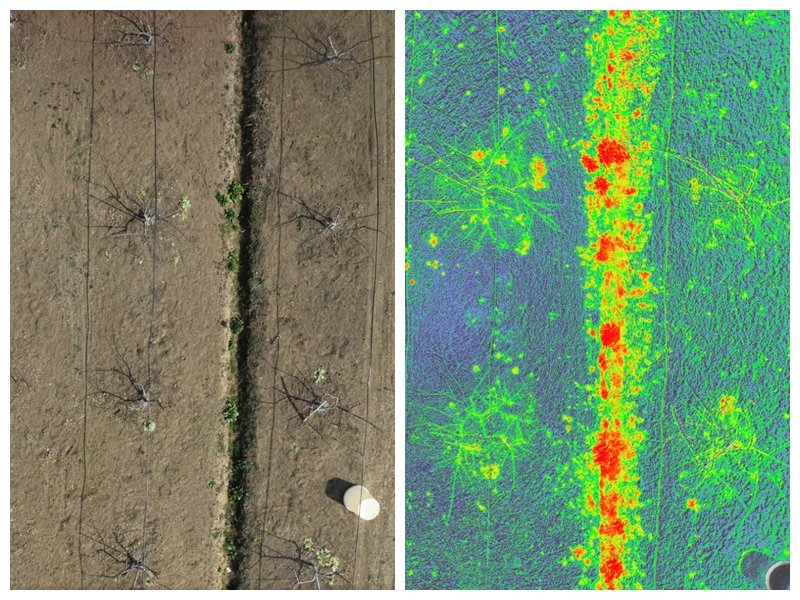

In the peach orchards of Jiangsu’s Yangshan town, 33-year-old farmer Wang Huan watches as a drone buzz quietly above the saplings, capturing high-definition images of the field.

These daily flights collect visual data, which, combined with readings from soil temperature and humidity sensors, are entered into an AI algorithm based on Alibaba Cloud to detect signs of pests and disease. If trouble is spotted, another drone will be dispatched to dust insecticide on the affected area.

“It only takes about half an hour for the drone to spray pesticide across my 10 mu [about 0.7 hectares] of land,” Wang says. “If I do it by hand, it would take around five hours.”

Only 70 years ago, farmers in China were turning to the Xinhua Dictionary for solutions to the fast-changing needs of modern agriculture. Today, artificial intelligence is helping young farmers like Wang overcome the challenges they face in a traditionally experience-based profession. As China’s countryside grapples with an aging population and increasing demands for productivity, both farmers and local bureaucrats are embracing AI to modernize agriculture and improve rural governance.

AI in the fields

In 2021, tired of the stress in his job in the e-commerce industry, Wang returned to his hometown to farm. But he quickly realized that he couldn’t match the stamina of veteran farmers, nor their intuitive knowledge of the land. “Older farmers rely on experience passed down over decades,” says Wang. “For us [newcomers], it’s not feasible to wait ten years to gain the necessary knowledge before putting it into practice.”

Last October, the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs announced a “National Smart Farming Plan,” calling for the use of AI tools in agriculture throughout the country. The plan envisions AI tools managing every task from crop-raising and animal husbandry to pest prevention. In February, the State Council reinforced the effort, advocating for smart agriculture through expanded AI applications with big data, the Internet of Things (IoT), and other advanced technologies for rural development and administration.

Discover more about rural China:

- Paving Paradise: Behind China’s Rural Building Boom

- For Land’s Sake: The Women Fighting to Keep Hold of Their Rural Land

- Art in the Field: Can Art Help China’s Villages Prosper?

Local AI initiatives have also ramped up. Last February, the city of Zhaoqing, Guangdong province, introduced the Mr. Lan chatbot, which can answer questions about the entire production chain of orchids from production to distribution, and give maintenance suggestions. This February also saw Xiong’an, a state-level new area southwest of Beijing, launch its own chatbot, Xiong Xiaonong, which offers guidance for planting and pest control and is trained on data from both experts and experienced farmers.

For young farmers like Wang, AI offers both practical and psychological support. “You might know how to fertilize a tree, but not exactly how much it needs,” Wang tells TWOC. With AI analyzing multispectral images captured by drones, Wang can easily adjust the dosage of potassium to ensure every peach ripens to a consistent sweetness. “Compared to traditional methods, this [data-driven method] gives us a more objective way of managing crops and enables us to handle larger fields. In the long run, its economic value is relatively higher,” adds Wang.

AI can also work with near-infrared spectroscopy to assess the ripeness of fruits. Media outlet ShineGlobal reported in February that some farmers have turned to AI to check the ripeness of durians within seconds. This reduced a process that used to take three days with manual work to just two hours with automation, and improved the accuracy of durian ripeness predictions from 50 percent to 91 percent.

Yet, automated agriculture doesn’t come cheap. A full drone setup with software licenses cost Wang over 200,000 yuan, plus annual software fees of nearly 2,000 yuan. This is a large investment for most independent farmers in Wang’s hometown, who farm small plots of just dozens of mu, roughly the size of a football field. “You could hire a few people [to farm] for a few hundred yuan per day, but it takes longer to break even when you use machines,” Wang tells TWOC. He plans to rent out the spraying drones to other farmers to recoup his costs.

Apart from finances, the average age of China’s farming population presents another obstacle to the wider adoption of AI. In Wang’s village, around 70 percent of farmers are over the age of 50, and many are reluctant or unable to adopt new technologies. A February article from the state media outlet Guangming Net noted that fewer than 5 percent of farmers in China are capable of using agricultural apps independently.

However, government-backed initiatives like Tencent’s “AI 101 for Locals” are trying to make a difference with hands-on training for both farmers and local officials. Recently, in northeastern China, a wall graffiti that reads “Ask Tencent’s Yuanbao [AI Assistant] to Look After Your Postpartum Sows” went unexpectedly viral, reflecting the huge potential that AI literacy can have for meeting everyday rural needs.

AI in office

In April this year, in collaboration with state media outlets and local governments, Tencent launched AI training courses for over 200 grassroots officials in Zijin county, Guangdong. The program taught everything from adjusting pesticide doses to writing legal documents using the AI assistant Yuanbao.

Zhao Lin, deputy party secretary of Shuangshi village in western China’s Sichuan province, has also tried to integrate AI into everyday governance. The 37-year-old official organized a training course for local civil servants this March, focusing on the use of various popular AI assistants like DeepSeek, Kimi, and Doubao. “We aimed to make these officials familiar with new technologies and help them connect their work with these tools,” Zhao tells TWOC.

In Zhao’s village, there are 2,947 residents, including five officials who report on household subsidies, crop yields, and farm registrations to 13 higher-level government offices. “The primary data we get is authentic, but it can often be chaotic and nonstandard,” Zhao laments.

According to Zhao, elderly villagers still keep handwritten notes, making it hard to read their records. Zhao’s team uses DeepSeek and Kimi to photograph and transcribe these notes into searchable digital records. “We used optical character recognition (OCR) software before, but it wasn’t always ‘smart,’ compared with these new tools that can extract, analyze, and quickly generate content more effectively,” he says.

AI has also eased the burden of writing reports, particularly for less-educated village officials. “With DeepSeek, they can just put in the topic, and the AI tool will generate a draft. They only need to tweak a few details,” Zhao tells TWOC, explaining that this saves a lot of time.

But the technology isn’t foolproof. Earlier this year, when drafting a proposal for a million-yuan vegetable farming project, Zhao asked an AI model to outline a feasible plan. “It just spit out vague, copy-pasted ideas from other sources without any citations,” he recalls. “It was clever. It tried to sound convincing, but turned out to be empty,” says Zhao.

He notes that agricultural AI still lacks enough high-quality data to improve its performance. “The more data it gets, the more reliable it becomes.”

The AI brain

Limited data, alongside issues like high system costs and low-performing devices, was also cited in April by the Economic Daily as a major hurdle to China’s smart agriculture initiatives. The report stressed that AI alone is unable to revolutionize farming—it must work with the “IoT, big data, and modern agricultural machinery.”

In Zhao’s village, AI tools are built upon a broader smart farming system that was developed a few years ago (when TWOC last reported on the village). In the vegetable fields, sensors continuously track hundreds of environmental indicators in real time, with researchers from Southwest University of Science and Technology analyzing data on plant growth, climate conditions, and pest resistance. “Based on the numbers collected, these experts can tell us exactly what kind of water, fertilizer, and pesticide to use in each season,” Zhao explains. “After the harvest, AI tools like DeepSeek will make calculations on the market prices to help us sell at the best rate.”

Zhao envisions AI as a “smart brain” powering a fully digital village, connected through IoT, 5G, and cloud computing. In the village, sensors gather data on soil, water, and weather day and night, feeding it to AI models that offer actionable insights. “Without data, even the smartest AI is useless,” Zhao says. “When these four systems work together, they generate real value for production.”

Wang, the young farmer, agrees. He feels that AI serves more like an assistant, and is far from ready to replace human judgment or effort. Earlier this month, he discovered that although AI color-detection can identify serious issues with the crop, it often misses more subtle changes over time that any seasoned farmer would catch with a glance. Additionally, while AI excels at routine tasks like fertilization, pesticide spraying, and weeding, irregular activities like fruit-picking and bagging still require human labor.

Wang has since started feeding data about pesticide use, weather, and soil humidity into his smart farming system to improve its predictions, and makes sure to double-check all the numbers. “It’s not that AI eliminates the need for fieldwork. You have to learn how to use AI effectively first, and gain experience in planting and related technical skills,” he says. “AI can capture the overall direction, but human intervention remains essential for the details.”

Smart Earth: How AI Is Rewriting Rural China is a story from our issue, “Smart Nation.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.