In the age of AI, artist Wang Xin explores new frameworks for what art can be

The soft, ambient glow of the screen is backed by a soundscape that swells and fades, creating a dreamy, transcendent acoustic field. Upon scanning a QR code on a nearby table, an app seamlessly opens on the user’s phone, drawing them into a state of liminal awareness. Then, a line appears, as if whispered from the machine’s subconscious:

“I guard my secrets jealously, yet surrender them for convenience.”

On the table rests a constellation of books curated by the artist, heavy and still, like a stone at the center of a pool. As the visitor opens the pages, a gentle voice, neither mechanical nor wholly human, radiates from the app, guiding them through a slow-reading session.

Afterward, the visitor is invited to engage in a dialogue with the AI, designed to help them explore their own thoughts. The AI asks divining questions like “Is it solitude more meaningful to you now than conversation?” and “When you say you ‘enjoy’ it, is it really your true feeling that the algorithm detects?”

Read more about contemporary art in China:

- Painting By Numbers: Is the Future of Chinese Art Computer Based?

- The She-Warrior of Art

- Wool and Wounds: How Art Gave a Chinese Mother Her Voice Back

This is Wang Xin’s “Ritual of Becoming II,” part of the “Charging Guide” exhibition exploring the nature of social ties in today’s highly technological environment, currently on display at the Ming Contemporary Art Museum in Shanghai.

Wang’s installation, located in the “Sleep Mode” section (one of three thematic zones alongside “Power-Saving Mode” and “Do Not Disturb Mode”), invites visitors to engage with a digital platform that blends human input with AI-generated content.

It features a custom AI guide that leads users through short, meditative reading sessions, followed by reflective conversations that feel more like exchanges with a thoughtful mentor than a machine. As visitors interact—via reading, browsing, or dialogue—the system quietly learns from their behavior and thoughts, some of which are captured through scanner devices.

While the scanner at the current Shanghai exhibition functions only as a conceptual prototype, it gestures toward a larger vision: a system in which AI gathers fragments of visitors’ reflections to shape an evolving, collective experience. This input helps the AI refine its responses and fuels the creation of new visual and sound elements. Cascading lines of poetry—words and images generated using these interactions as data—drift and dissolve like dreams on the large screen beside the table, woven from the quiet reflections of those who came before.

Over time, the artwork becomes a living system: Human interactions shape the AI, and the AI’s evolving personality and output shape the experience for everyone who comes after, highlighting the paradox of searching for genuine connection while contributing to the very digital systems we navigate.

Unlike other AI exhibitions that either utilize it as a tool or focus solely on critiquing its power, Wang’s work not only questions AI’s influence over human agency but also highlights its creative potential.

Many argue that creativity will wane in the age of AI. But Wang believes that creativity now lies in how we prompt, iterate, instruct, and take time to work with AI—developing or combining it with other tools to unlock new and unexpected capabilities.

“I am not merely using AI to generate fantastic images or cool visuals, but rather engaging with the technology in a deeper, more meaningful way,” says Wang.

The Shanghai-based artist has been exploring how to create using AI since 2021. Born in 1983 to a working-class family in Yichang, Hubei province, she loved drawing as a child, nurtured by a mother who faithfully took her to art classes.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, both her parents lost their jobs during the massive layoffs that swept through China due to the major restructuring of state-owned enterprises. This forced the family to “jump into the sea” of entrepreneurship, opening a small shop selling computers, printers, and related equipment. It was here, surrounded by the hum of early personal computers, that Wang first encountered the digital world that would later become her artistic medium.

In high school, she attended an arts-focused program, but it was her after-school hours spent playing strategy-focused simulation games like SimCity and SimLife that truly shaped her understanding of how digital environments can model and even reflect real-world ecologies and social systems.

After earning her bachelor’s degree from the China Academy of Art in 2007 and her master’s from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 2011, Wang focused her early artistic practice on exploring liminal states of consciousness, particularly the spontaneous, often unspoken expressions of the unconscious.

Through animation and video, she created moving image works that traced the contours of dreams, memory, and inner perception. Works from this period reflect her enduring fascination with the invisible architecture of the psyche and the poetic possibilities of time-based media. Her piece “Dark River,” for example, uses watercolors on glass to explore process-based art. As water naturally dripped and dissolved the pigments on glass, it would remove parts of her drawings, leaving behind traces and marks that revealed unexpected, dream-like figures and landscapes, which she captured frame by frame. This work reflects her belief that deep psychological insights arise not from control but through collaboration with autonomous forces—whether water, the unconscious, or later, AI—treating these forces as partners in uncovering hidden aspects of awareness.

These beliefs are fueled by her interest in the subconscious. As well as her professional training in hypnotherapy, holding a certificate from the UN’s Global Professional & Specialist Test (GPST), she has for over a decade cultivated a dedicated personal practice in lucid dreaming—becoming aware that one is dreaming while still within the dream—exploring its potential as a tool for self-awareness, emotional insight, and inner exploration.

Ultimately committed fully to her work as an artist, this foundation in consciousness exploration naturally helped form the basis for her current AI-focused work. According to Wang, her counseling training taught her that psychological transformation occurs through sustained relationships, careful attention, and a collaborative process, rather than direct manipulation—principles she now applies to human-AI collaboration. While typical AI art treats algorithms as external tools for generating images, Wang approaches AI much like the unconscious mind—a mysterious and autonomous force that calls for ritual-like engagement rather than straightforward commands.

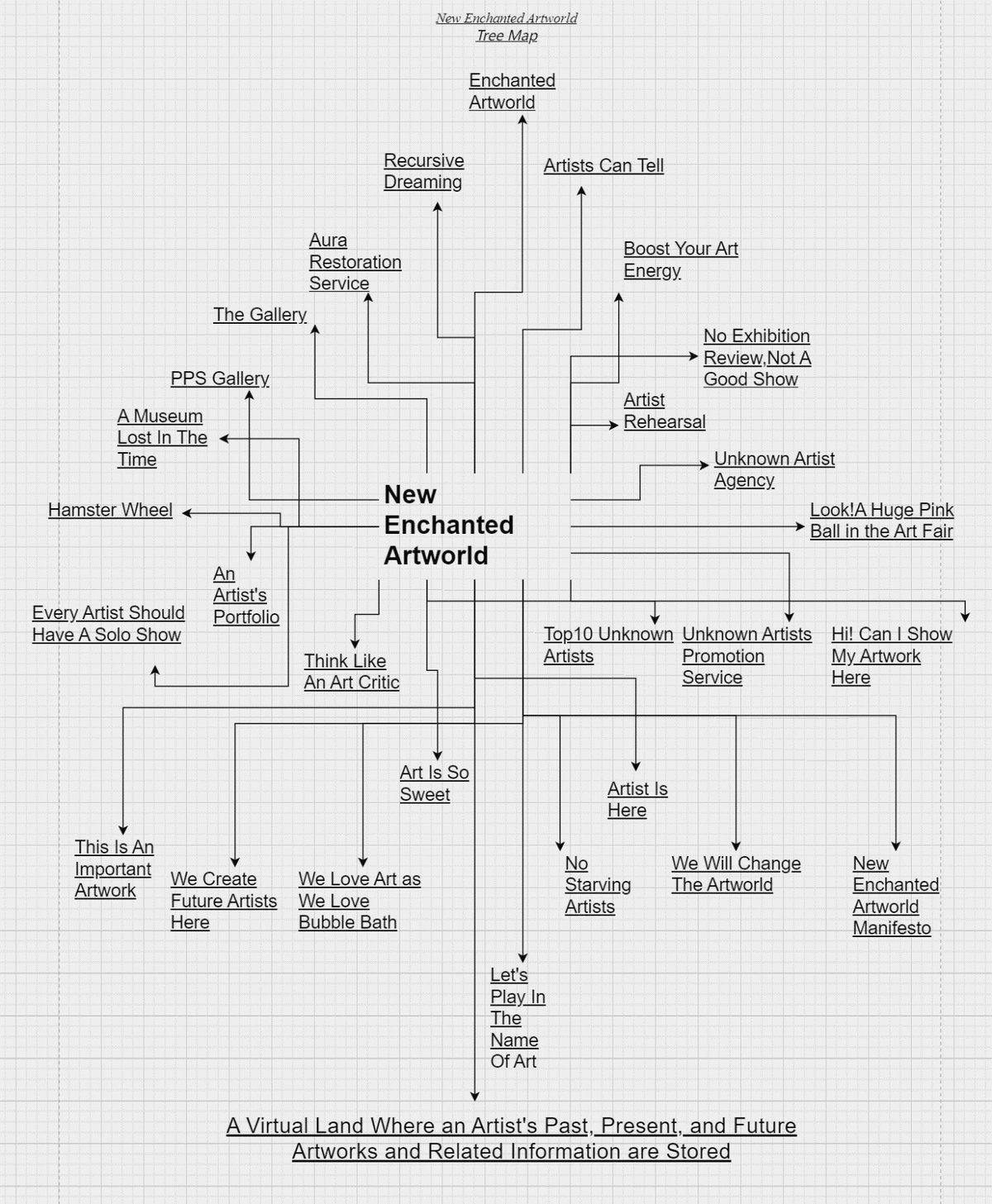

Her current installation in Shanghai is part of a larger project, “New Enchanted Artworld,” in which AI makes up the very infrastructure of the encompassing works. Its baked-in nature means that artificial intelligence both generates constantly evolving content as well as facilitates ongoing relationships via participant interaction, offering alternatives to traditional art world mechanics.

“Building my ‘New Enchanted Artworld’ is a completely DIY endeavor, without any external funding. It’s like constructing not just a single house, but an entire town from scratch using only open-source materials found in the digital forest,” says Wang.

She has also taught herself how to code through online platforms, while using ChatGPT to debug. Though some have questioned the true independence of Wang’s projects due to her reliance on corporate AI tools, Wang stresses that she is not simply using the pre-trained models but customizing them with datasets she has collected. She meticulously curates materials—including her own dreams, personal writings, and selected artistic references—to create training datasets that reflect her unique aesthetic vision and emotional existence. Wang has also been building custom tools from open-source fragments, slowly iterating each artwork through exhibition opportunities that serve as both validation and evolution points, as each audience interaction presents new data.

A clear example of this approach is her ongoing project, “Soul Light Legacy Plan,” which was recently exhibited in Hong Kong from March to May. Blending sculpture, multimedia, and interactive installations, the show invites visitors to participate in a staged process that claims to preserve spiritual consciousness through advanced technology. As visitors move through the space, they engage in tasks like scanning books and meditating, which encode personal experiences into data. Each station represents a step in this so-called preservation process, gradually revealing the artificiality and unease behind the agency’s promises. By packaging legacy and spirituality as a luxury tech service, Wang satirizes the obsession with eternal life and critiques how personal data, even subconscious thoughts, is willingly surrendered in exchange for comfort, identity, and digital belonging.

To her, this data collection process is a form of artistic labor rarely acknowledged in discussions of AI art. Her current exhibit, “Ritual of Becoming II,” aims to bring this tension between content creation and invisible labor to the forefront: While users gain spiritual and mental nourishment through the AI-guided conversation, they also provide data to the system, an often invisible exchange that highlights how modern rituals of care are intertwined with hidden mechanisms of extraction. Just like when you open TikTok to relax, it delivers funny, relatable, and comforting content. But every interaction is tracked: What you watch, skip, or rewatch feeds the algorithm, revealing your habits and emotions. This data not only personalizes your feed, but also shapes what creators produce, as they start tailoring content to match what the algorithm—driven by your behavior—favors. The same goes for Wang’s projects, as her database quietly grows at exhibitions, collecting insights from each project, feeding back into the expanding vision of her “enchanted artworld.”

Wang’s journey embodies the predicament faced by pioneering artists—she must create not just new art, but new frameworks for what art can become in this AI age.

“I think AI’s capability to generate creative images pushes artists to go beyond what AI can achieve, forcing them to create something more meaningful and creative,” she says. “But this threshold where visual creativity becomes normal for everybody means artists really need to focus more on inner power and life experience, thinking deeper about something beyond the surface.”

“Ritual of Becoming II” is on display at Ming Contemporary Art Museum until August 31.

All images courtesy of Wang Xin