How crypto-artist Reva combines her love of coding with artistic creativity

Reva says she creates the same way that clouds form in the sky.

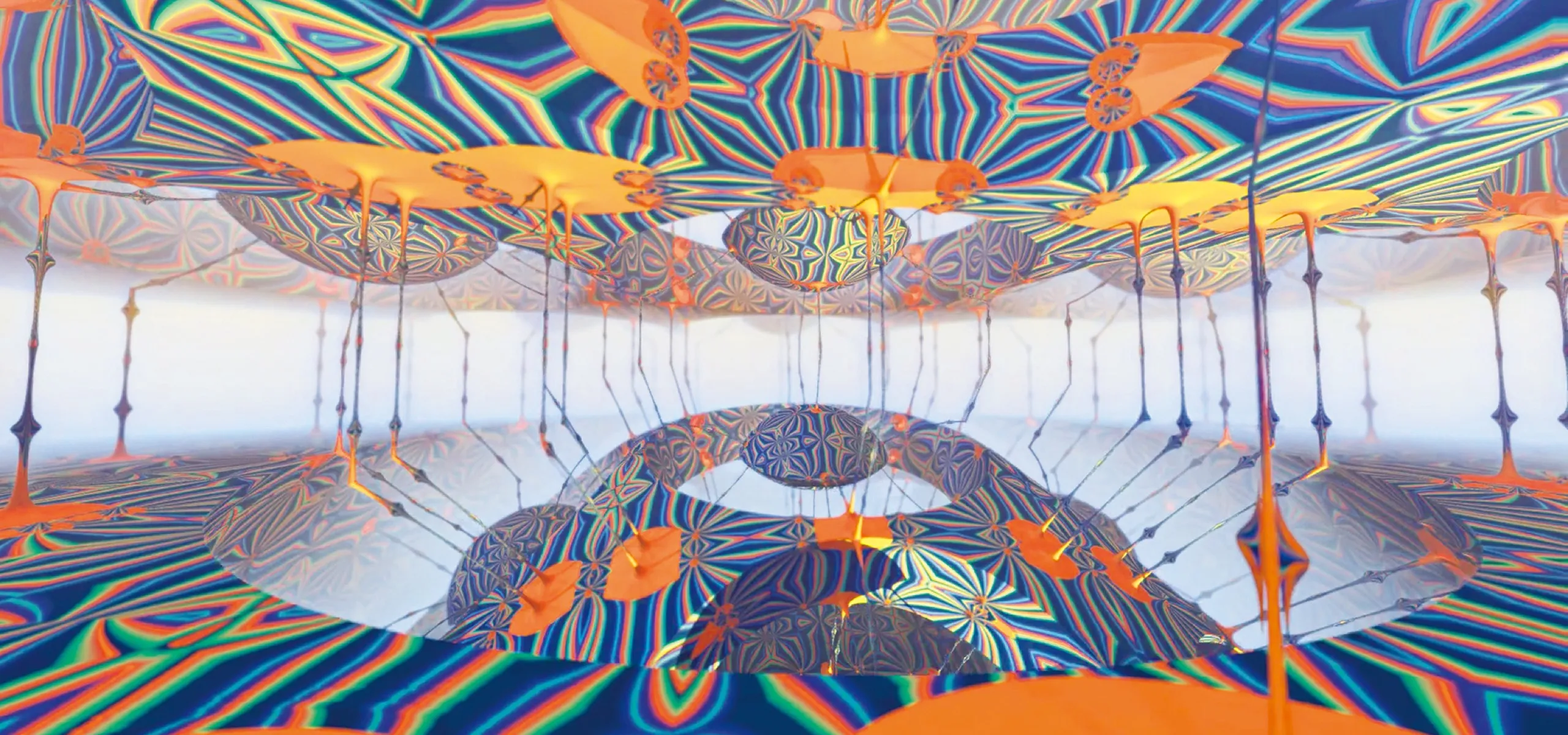

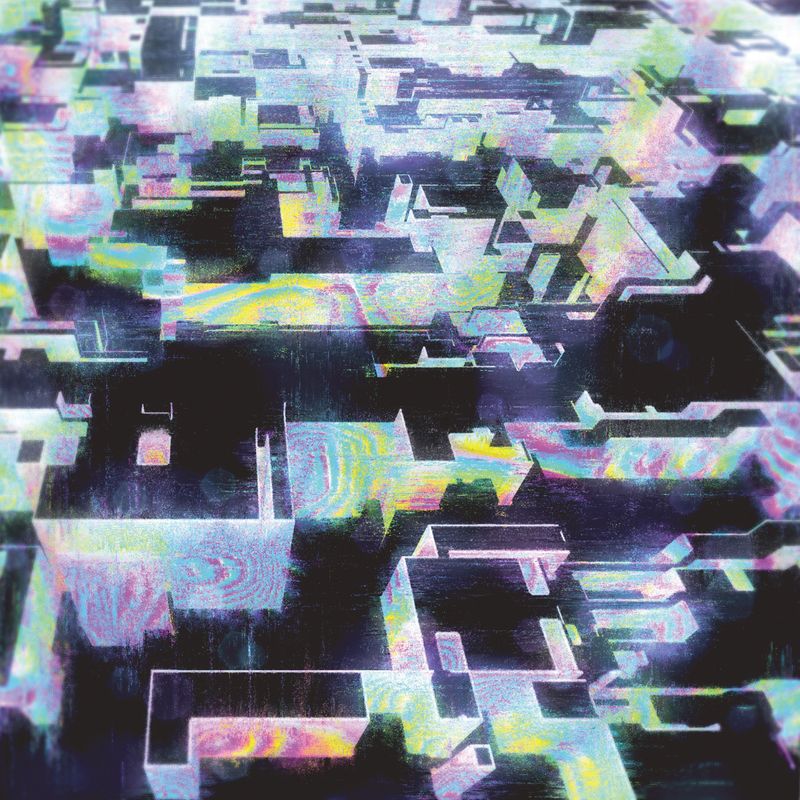

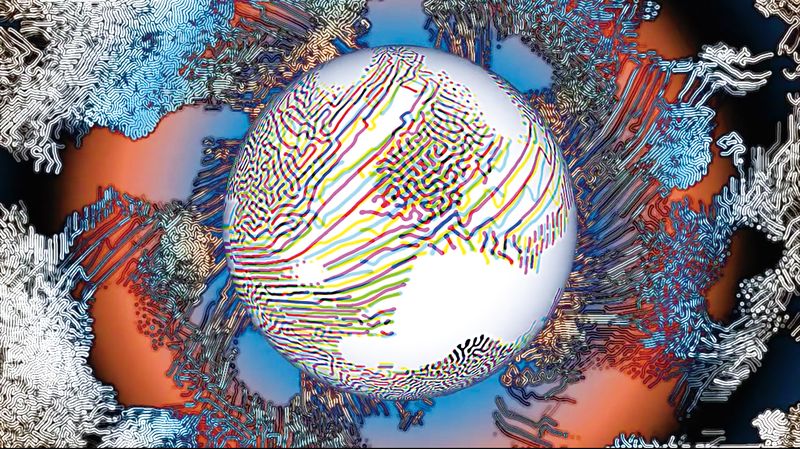

To watch a video of her work process is to see order form out of chaos. A string of numbers, letters, brackets, and semi-colons written and rewritten, copied and pasted and tinkered with. They mushroom into paragraphs, germinating spectacular images as they grow and grow.

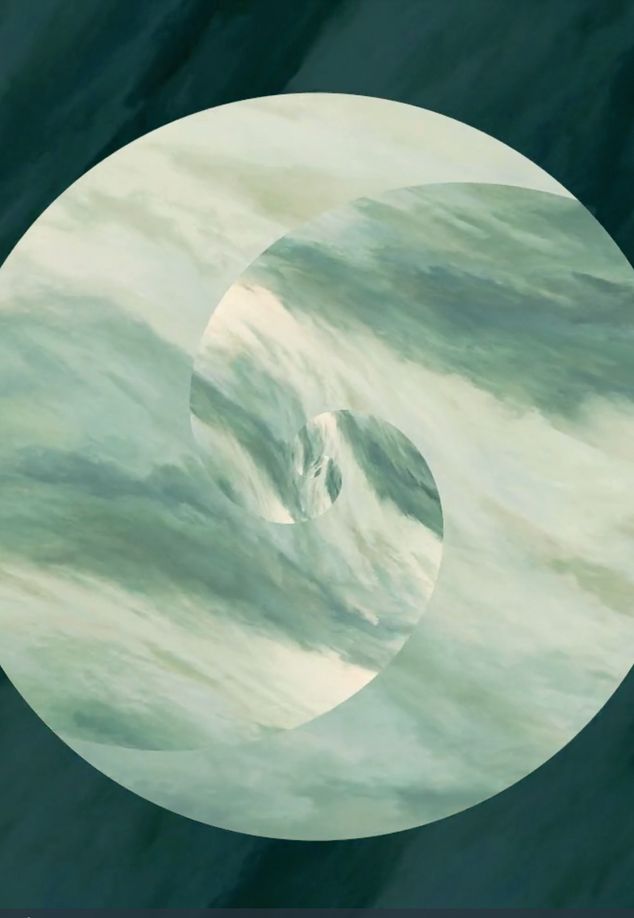

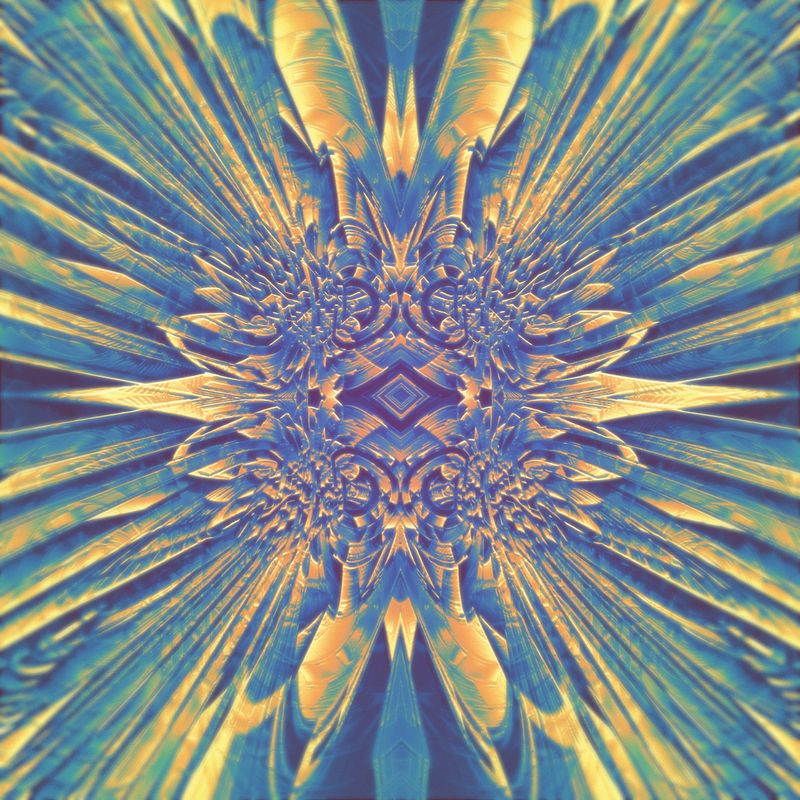

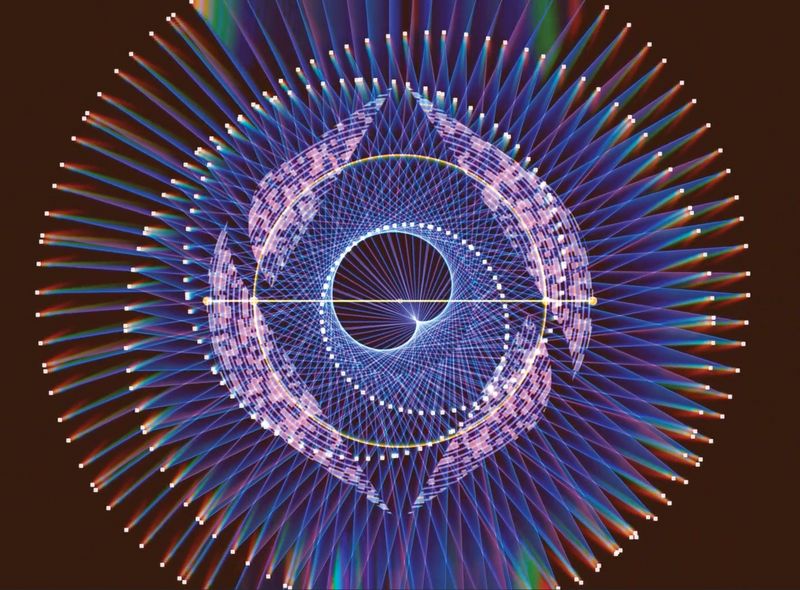

Like the first wisps of cloud, these strings of code “can grow from a small point”; and with a few small random changes, the code can end up creating an infinite number of shapes. Most of the time when she creates this computer-generated work (known as generative art), Reva is just “playing around” on her laptop with no idea what the final product will look like—an infinite plane of creation. In works like her Flowing Nautilus series of 2020, the speed, flow, and colors that cascade over the crisp lines of a flowing spiral are quickly transformed by switching a few numbers in the code to create a wholly new piece.

Many look at this field of computer-based art, and, blinded by the magic letters NFT, for Non-Fungible Token, see big business. But for 36-year-old Reva, whose real name is Fan Yiwen, it’s just “a lot of fun.”

Reva is a crypto-artist, whose tools are algorithms and coding software, whose copyright is blockchains and NFTs, and whose galleries are a plethora of NFT-trading platforms worldwide. Speaking over the phone with TWOC from her apartment in Shanghai, Reva (originally from Shenzhen) humbly calls herself a “nerd.” With an awkward laugh, she explains how she has a “kind of boring” daily routine, and gets excited about coding, something she will often do into the small hours of the morning.

But she’s also experimenting with some of the newest art mediums on the block which she believes will have “many more opportunities” as the technology continues to develop.

She is at the forefront of a technological revolution, among other creative-types nerdy enough to know how the latest technology works, but also imaginative enough to experiment with what it can do. It is a “movement born somewhere between the buzzing hallways of blockchain conferences and the tiny corners of cyberspace,” as pioneer crypto-artist Olive Allen eloquently explained to the magazine Flash Art this January; a place “where, late at night, a handful of rebels and misfits were trying to satisfy that unexplainable urge to change something in the world.”

There are only a few artists working in this form, says Reva. To her, works by the names that everyone sees as the forefront of the NFT world, like Beeple, CryptoPunks, or the Bored Ape Yacht Club, are just “digital paintings.” Her work is much more complex, based on algorithms, fractals, and code written by herself, and “cannot be done without blockchain technology.”

Blockchain technology aims to transfer power away from those who dominate the internet today: governments and conglomerations. But it also loosens the grip of the artistic establishment. Without crypto-art, Reva believes she would not be considered an artist. She had always been interested in art, drawing as a child, but as her university was an institute of technology rather than an art academy, “I was not in the system.” She lacked the background to be able to work with the galleries and museums of China’s art establishment.

“Her passion is in computer science, math, and functions,” says a gallerist working in China’s contemporary art market and aware of Reva’s work, who requested anonymity. For the gallerist, Reva’s exploration of what the software can do could be part of the future of art in China. But the collectors she deals with aren’t tempted by anything crypto- or NFT-related, buying art that follows academic criteria. “I don’t think they want to comprehend it,” she says. “It’s like the old generation with new tech.”

It’s this new tech that Reva majored in: the methodical, practical field of computer science; she then worked for six years as a computer engineer, creating visual effects for VR and the film industry. But she was exhausted with the tech industry’s tough working hours, and a culture among developers that valued “hype” over “working hard on the development of the technology.”

But whereas blockchains began to form in the West in the early 2010s (with some believing the first piece of NFT art was made in 2014), China was late onto the crypto-art scene. Indeed, the first crypto-trading institution in China, BCA, was only set up in 2018. Fledgling auctions and exhibitions were set up the next year: Liu Jiaying, also known as CryptoZR, created the work 1000EYE just after completing her master’s degree course at the Central Academy of Fine Art. Also in 2019, another celebrated Chinese crypto-artist named Song Ting set up an exhibition of blockchain art at the Today Art Museum, Beijing. This was long before NFTs went mainstream in 2021, thanks to the sale of “Everydays: The First 5000 Days” by Beeple, or the purchase of CryptoPunks or Bored Ape Yacht Club NFTs by celebrities.

The commercial boom following Beeple’s sale rippled over to China, but the number of serious artists working in this field in the country is still small. An exhibition organized by Song Ting in July 2021, which showcased the finest artists, curators, and institutions in the Chinese field, only included 55 Chinese artists.

“We three [Reva, Song Ting, CryptoZR] are actually the promoters or pioneers in this field in China,” says Reva. She herself found out about NFTs via an article on WeChat in early 2020. Excited that there was a way to combine her area of expertise with the art world, she launched her first NFT series, Chasing the Moon, in September 2020.

Ever the engineer, most of Reva’s thinking behind her work seems to have gone into the technological means, rather than the artistic ends. When asked what inspired her to create a collection of NFTs on the trading platform Foundation, with curious titles like “Do Bacteria Dream of Electronic Chips?,” her reply goes immediately to the coding, explaining to TWOC how much “simpler” it was to write the code for these than for some of her more ambitious projects.

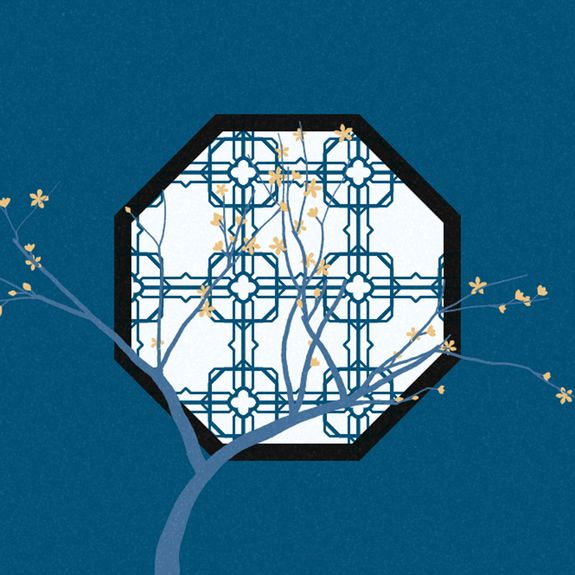

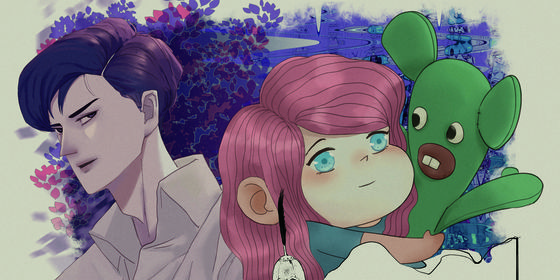

Her more complex projects include Through the Window with Art Blocks, a platform on OpenSea that, according to Reva, is totally different from other platforms. These NFTs don’t look like much, spindly trees blossoming at random in front of patterned Chinese windows in various block colors; the stuff of Microsoft Paint.

But the technology is cutting edge. Instead of an artist uploading a finished image, Art Blocks allows a generative artist to send an algorithm, which is only activated if purchased, whereupon it is converted into its visual form. This form of generative art, according to Reva, takes the longest to produce, with hundreds of possible results which are dependent on the code generated for the buyer. For Reva, this is an exciting, highly creative process, “like a game or like a blind box,” where even she does not know what the final image will look like.

Such projects take a lot of time. Reva says it can take up to a month to get a generative piece right, with 80 percent of that time spent trouble-shooting, clearing out the bugs that could make an artwork go haywire.

Given her field, it’s perhaps no surprise that Reva takes inspiration from science fiction classics. For example, her artwork “Do Bacteria Dream of Electronic Chips?” is a nod to the Philip K. Dick novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (which is the basis for the sci-fi classic Blade Runner). “I like sci-fi movies,” she says simply, adding that she often studies the striking visuals of cult classics, like the shimmering multi-colored lights from the famous “Star Gate” scene, when astronaut Frank Bowman is sucked through space and time in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey.

According to database CryptoArt, Reva has now earned over 100,000 US dollars in sales. This is not as much as the earnings of Song or CryptoZR, but still enough to allow her to rent apartments in both Beijing and Shanghai at the same time.

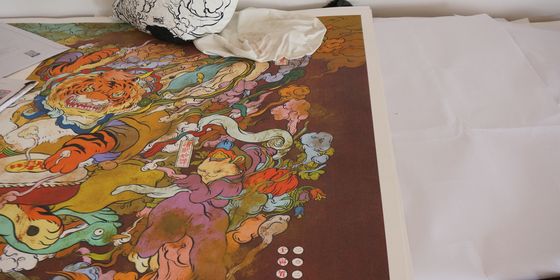

Despite Reva’s modest success, Chinese crypto-artists are small in number and were late to the space, so have a lot of catching up and self-promotion to do if their voices are to be heard. “I want to bring some Chinese style to the crypto-art field,” she declares, saying she finds great drama and potential in the aesthetics of traditional Chinese styles.

One of her aims, she says, is to combine traditional art with the latest technological innovations.

The first NFT she made, Chasing the Moon, back in September 2020, portrayed the celestial body through the swirling lattice of a traditional Chinese window. Flowing Nautilus was inspired by the fluidity of tai chi. She is continuing to explore the theme of traditional Chinese art in collaboration with a Japanese gallery that reached out after seeing Through the Window on OpenSea.

Nevertheless, promotion remains a major challenge, Reva says. She mostly promotes her work on platforms for discussion among NFT communities, such as Twitter and Discord. She also founded a group called WeirDAO in 2021, for Chinese independent crypto artists.

DAOs, which stand for decentralized autonomous organizations, are collectives where no single member has control over the group. The members have all joined together in pursuit of a common goal—be it investing in the metaverse or scouting out the next hot NFT artist.

WeirDAO is a small community of 18 artists who meet up online once a week to chat and share opinions or professional opportunities. Decisions on group projects are put to a vote, but it’s not easy. During their weekly meetings, Reva notices it is always the same few people who speak up. Perhaps this is because artists are solitary, reserved people, Reva suggests; or it may also be that Chinese are not used to the decentralized structure of a DAO, preferring a leader to coordinate them and give “orders.”

The group have collaborated on three exhibitions to date. The most recent was held on Voxels, a virtual world space, allowing a set of anonymous artists to vent their anger (but not too much) about Shanghai’s recent extended lockdown. The space included NFTs themed around the endless cycle of Covid testing and tracing, and the unhygienic conditions at some makeshift Covid hospitals. “We just want to record our emotions and feelings,” says Reva.

With a bit of luck, hopefully Reva’s DAO can grow from a small point into something spectacular. Just like her clouds.

Images by Reva

Painting By Numbers: Is the Future of Chinese Art Computer Based? is a story from our issue, “Public Affairs.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.