Since its founding in 1999, the Harbin Ice-Snow World has grown from a local initiative that provides residents with wintertime entertainment into the world’s largest celebration of ice

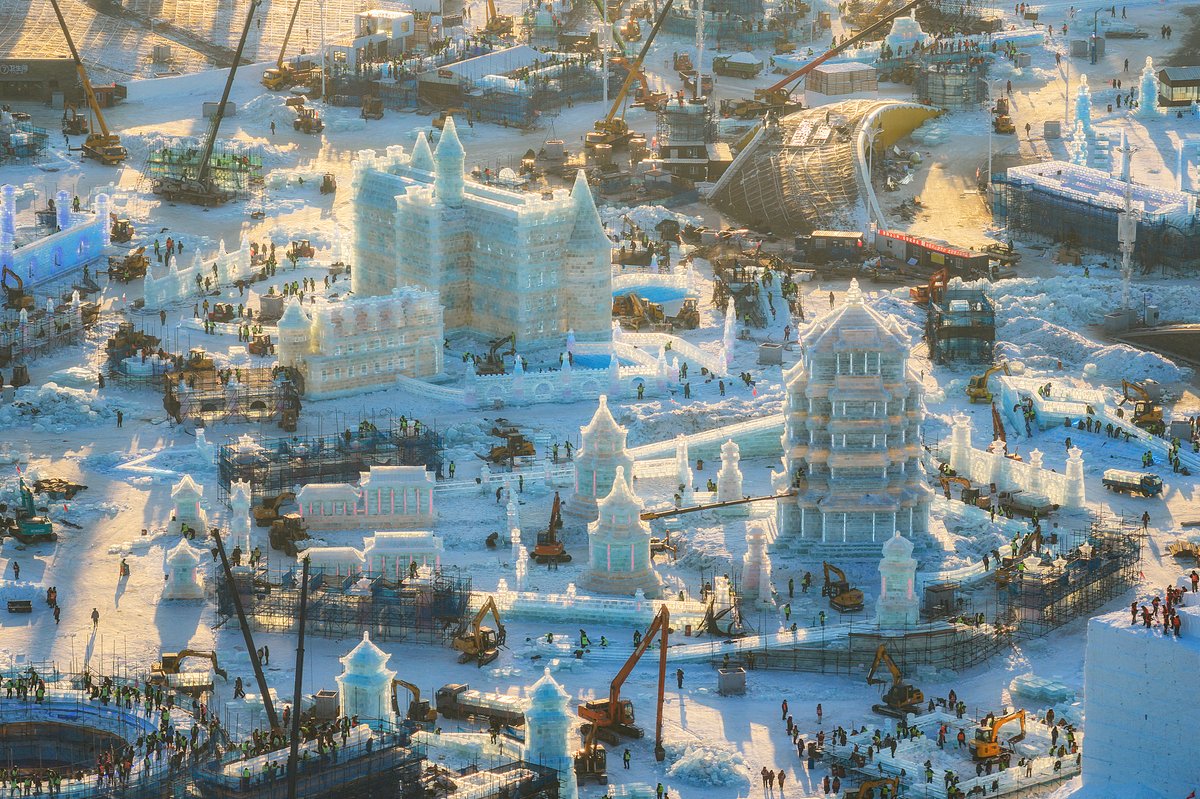

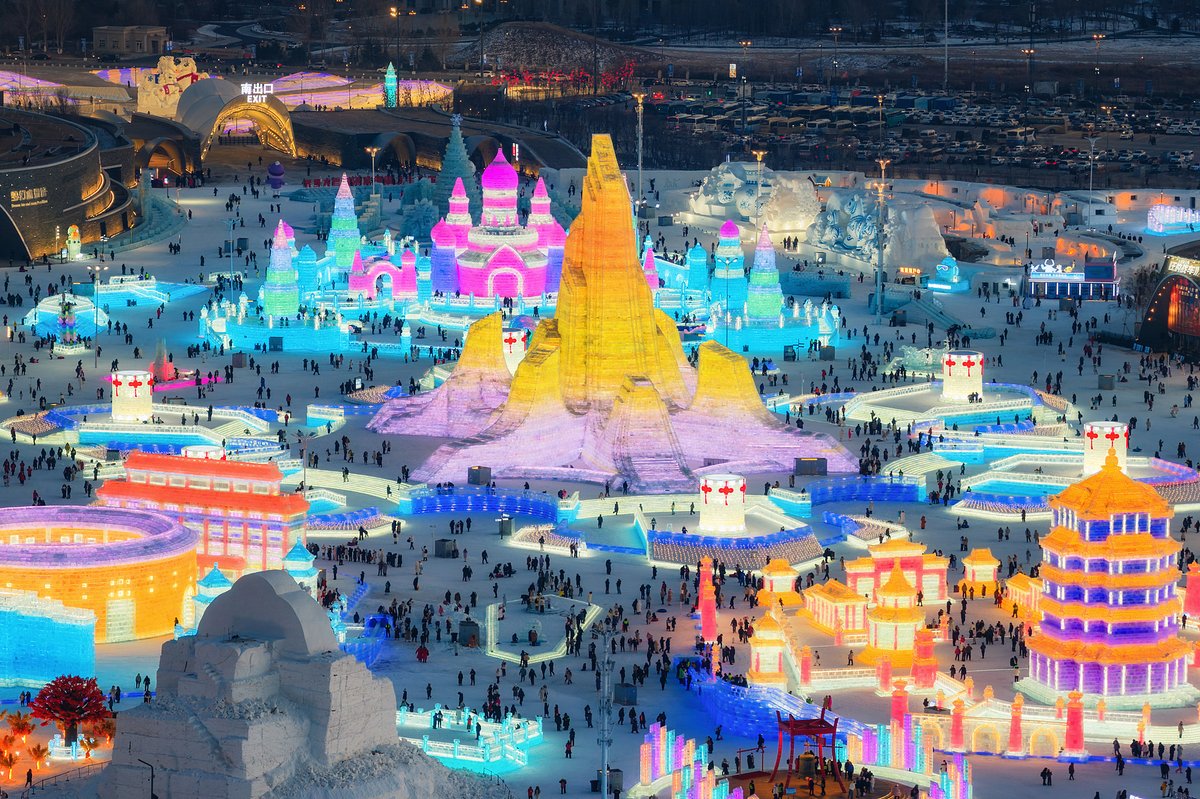

When much of China retreats indoors during the winter, the northeastern city of Harbin does just the opposite. By mid-December, a second luminous and crystalline ice city begins to rise beside the city’s Songhua River, featuring majestic castles, towers, and sculptures bathed in shifting colors. Despite temperatures plunging to as low as -30 degrees Celsius, excited laughter and exclamations, spoken in an array of accents, echo late into the night from ice slides that stretch hundreds of meters. Each year, the Harbin Ice-Snow World rises from hundreds of thousands of cubic meters of ice, assembled in less than a month by tens of thousands of workers—ice sculptors, chainsaw operators, ice carriers, and others—laboring around the clock to bring the frozen city to life.

Officially opening its gates on December 17 this year, the ephemeral park—spanning an area equivalent to 168 standard football fields—is the centerpiece of the months-long Harbin International Ice and Snow Festival. The festival has anchored the city’s winter tourism for the past two decades, and in the past two years, its impact has grown even stronger as the city has gained renewed visibility amid China’s post-pandemic domestic tourism boom. It remains open for approximately two months, until rising temperatures can no longer sustain it—a seasonal ritual now in its 27th year.

Read more about China’s northeastern provinces:

- Dongbei Survival Guide: A Language Guide To Speaking Authentic Dongbeihua

- Dongbei Diaspora: Why Are Northeasterners So Unwilling to Return Home?

- “Fire Spoon”: A Lesser-Known Dongbei Treat

“The Ice-Snow World was my main motivation for visiting Harbin—it felt truly iconic, since I’ve always longed to experience heavy snowfall,” says Wang Yuanmeng, a 22-year-old from Hunan who visited Harbin in February 2024.

According to local government data, Harbin logged over 90 million visits during the 2024 to 2025 winter season, with international arrivals nearly doubling compared to the previous year, generating a total of 137 billion yuan in tourism revenue. Harbin Ice-Snow World alone received around 3.6 million visitors during its 68-day run, with ticket prices ranging between 200 and 350 yuan.

The Ice and Snow Festival has its roots in centuries of regional winter culture. During the Qing dynasty (1616 – 1911), Beijing’s Manchu rulers, originally from the northeast, designated ice activities as a national custom. Each year, they held parades and competitions on the capital’s frozen royal lakes—a reminder to the nobility not to forget their roots.

In Harbin, folk practices until very recently included cutting blocks of ice from the Songhua River and using them as natural refrigerators to preserve winter food and to make “ice lanterns,” a folk invention later turned into an art form.

“In Harbin, the sun sets very early in winter, and power outages were frequent. Households often relied on candles,” recalls Jiang Yiren, a Harbin native born in 1962. “People would take a small bucket, fill it with water to form an ice shell, and place a candle inside.” This way, the courtyard was lit, but the risk of the candle being blown out or accidentally setting fire to nearby lumber was eliminated. But because such ice lanterns were closely tied to humble living conditions, Harbin locals for a long time called them “poor man’s lanterns.” That perception soon changed.

In the 1960s, the city hosted its first ice lantern festival, partly to encourage residents to engage in outdoor winter activities. While it was nothing like the grand spectacle we see today, the six-day event with colorfully lit ice lanterns and ice sculptures drew 250,000 visitors, about one-tenth of Harbin’s population at the time. Following its successful debut, the ice lantern festival became an annual winter tradition. In 1985, the Harbin Ice and Snow Festival was officially founded, complete with a one-day public holiday for residents, marking a significant expansion of the event’s scale and offerings.

“To Harbiners, the Ice and Snow Festival is arguably the second most important holiday after the Spring Festival,” says Hu Shufang, a retired civil servant who worked on the planning of the Ice-Snow World project. “In the past, Harbin would grow quiet after dark, but it’s now a sleepless city.”

Hu, now 76, recalls early discussions about the project—initially conceived as part of the city’s plans to usher in the new millennium—that helped shape the park as it exists today, though not without controversy. Planners debated whether to build it on the Songhua River’s north bank, then largely wetlands, or on the more developed south side, which had already grown into an urban center with heavier foot traffic and better public transit. Ultimately, they chose the north bank, betting on its capacity to accommodate large crowds and encourage more balanced development on both sides of the river. In hindsight, Hu believes it was the right call.

“The north bank is now the Songbei New District, home to countless high-tech industries, a university town, and upscale residential areas—development that I believe was largely driven by the Ice-Snow World,” says Hu.

After just 33 days of work by more than 5,000 construction workers, the first 200,000-square-meter Harbin Ice-Snow World was completed on Christmas Day, 1999. On December 31, a 45-second clip aired during China Central Television’s live millennium New Year’s Eve broadcast introduced its huge ice sculptures and slides to a global audience.

The theme park welcomed over 500,000 visitors in its first year. Since 2000, the park has also hosted the annual opening ceremony of the Harbin International Ice and Snow Festival on January 5—an event officially recognized as one of the world’s four major ice and snow festivals, alongside Japan’s Sapporo Snow Festival, Canada’s Quebec Winter Carnival, and Norway’s Oslo Ski Festival. The Ice-Snow World has since expanded to encompass over one million square meters, with multiple different themed zones each year.

At the end of 2023, the park unexpectedly went viral on Chinese social media, thanks to a shrewd campaign by the organizers. Facing a series of complaints from tourists about long waiting times, they quickly refunded disappointed visitors, extended opening hours, and improved crowd management. Riding the wave of online attention, the local tourism authority also launched free shuttle buses, arranged flash mob performances at Harbin’s airport, and cracked down on tourist fraud.

Visitors began to pour in from around the country, especially from the snow-scarce south, drawn by affordable prices, friendly locals, postcard-worthy winter scenery, and a hint of European architectural flair shaped by the city’s proximity to Russia.

“The ice sculptures and winter activities were absolutely breathtaking for a southerner like me,” exclaims Wang, the student from Hunan.

The park, too, saw a surge in popularity, with visitor numbers nearly quadrupling from 800,000 the previous year to almost 2.7 million by the time the snow season ended in early 2024.

This year marks the park’s largest edition yet, featuring a giant ice slide topped with an “Ice Great Wall,” complete with ice-carved battlements and beacon towers, creating an immersive experience that evokes an ancient frontier—albeit one that flashes and shimmers in multicolored light. Meanwhile, the slide retains its impressive 521-meter length and a 21-meter vertical drop—equivalent to a seven-story building—the thrilling descent taking just about 50 seconds.

Li Bin, who requested use of a pseudonym, worked on the park’s grand ice slide project and expects both the city and the park to receive even more visitors than in the past two years. He says that the surge in popularity is no coincidence. “It has been built detail by detail, by both residents and industry practitioners, reminding us how crucial standardized service and reputation management are,” Li says.

To better accommodate travelers, the park’s authority has taken steps to make visitors as comfortable as possible. Li tells TWOC that, building on last year’s improvements—such as nearly 300 meters of windproof, heated shelters—this year also includes a fully heated waiting hall, meaning visitors no longer have to endure the cold while queuing to enter the park.

Outside the park, local culture and specialties also got their moment to shine. Frozen pears are served sliced, and roasted sweet potatoes come with spoons—all practices unfamiliar to locals. Performances by Oroqen reindeer herders, as well as practitioners of datiehua (打铁花)—China’s intangible cultural heritage “fireworks” performance involving hammered molten iron—greeted visitors.

“Harbin has been building this step by step, accumulating experience over time. It’s like, last year we could build an ice structure 10 meters high, and the next year we would reach 13 meters—progress is gradual,” says the Harbin native, Jiang Yiren.

Those enormous ice and snow sculptures, seen in both the Ice-Snow World and in many of the city’s free public parks, are another major Harbin attraction. From life-size replicas of the Terra-cotta Army to Paris’ famed Notre Dame Cathedral, Harbin’s ice sculptors can recreate almost any object or building imaginable through their master craftsmanship, now a provincial-level intangible cultural heritage.

“[But] in the early days, there weren’t many professional carvers,” Zhang Weihong, an ice sculptor who previously led ice construction teams for the Harbin Ice-Snow World’s displays, recalls. “In the 1960s, they used tools like axes and kitchen knives. With little precedent to follow, we gradually began making our own tools.”

Zhang is unlikely to have imagined how rapidly Harbin’s ice and snow carving industry has developed in just a few decades. A 2024 report by Jiefang Daily noted that the city now boasts a workforce of over 40,000 ice and snow sculptors, a benchmark that Zhang says demonstrates the world-leading level of its local craft. He adds that the tourism boom has helped preserve and pass down these skills. “Now, parents who follow my work add me on WeChat, asking when our studio holds classes and if they can bring their children to visit,” says Zhang.

Hu, the former government employee, is also optimistic about the future of the Ice-Snow World. “China has over a billion people, and still very few have come north to see what it’s like here,” she says.