Digital tombstones, QR code epitaphs, livestreamed rituals: This Qingming Festival, Chinese are turning to digital technologies to remember their ancestors

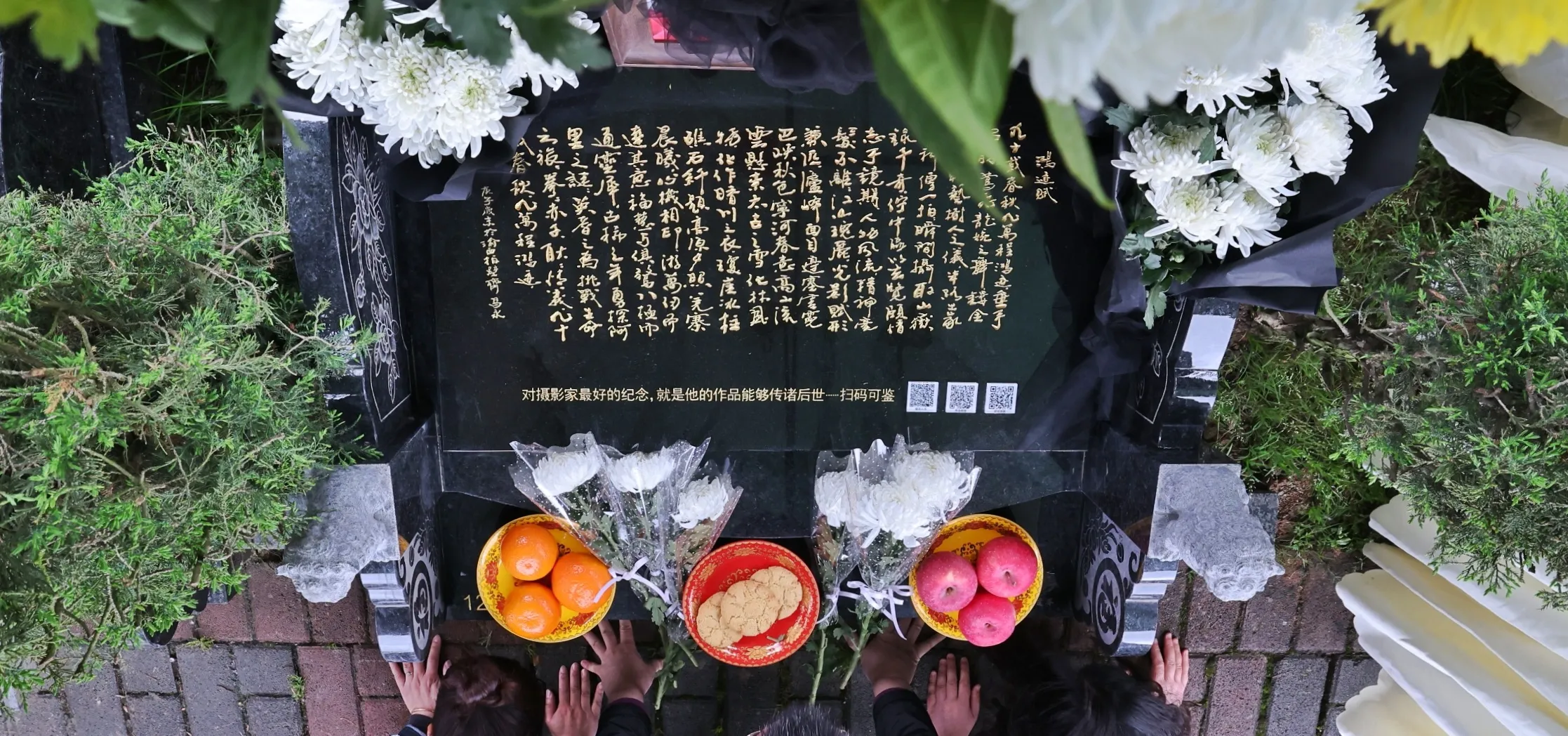

How do you condense 90 years of life into a single-paragraph epitaph? When Lu Gang’s father passed away last August, Lu found the task impossible. Eventually, he turned to a digital solution instead: three QR codes printed and stuck to his father’s grave. Scanned with a smartphone, they reveal dozens of photos and descriptions of the man’s rich life over decades.

This Qingming festival (清明节), when Chinese traditionally return to the graves of their ancestors to clean them and pay their respects, Lu, from Chongqing, shared images of the QR code on his WeChat feed, so those who knew his father but couldn’t visit his grave could still reflect on his life. The codes have been scanned over 63,000 times so far. “I don’t think he would mind that I put his life into a QR code. He was always passionate about embracing new technologies,” Lu says, recalling how his father, a photographer by trade, was adept at ordering takeout on smartphone apps even into his 80s.

Digital technologies are bringing new twists on traditions to Qingming Festival, funerals, and remembrance of the dead. Livestreamed rituals, digital tombstones, and QR code epitaphs have all spread in recent years, making paying one’s respects more convenient than ever.

In Anji, Zhejiang province, for example, a cemetery offers online memorial services for those who can’t visit in person. “We developed an online memorial app that allows people to register with their family members’ names to create a virtual cemetery. It was especially popular during the pandemic,” the cemetery keeper, surnamed Cai, tells TWOC.

Since Qingming Festival (also known as Tomb Sweeping Festival in English) is only a one-day public holiday and many Chinese live and work far from their ancestral hometowns, such online services are increasingly popular. For those who can’t make it back to clean their ancestor’s tombs or present offerings, there are ”tomb sweepers” for hire online who can perform the rituals in their stead, for a fee.

On e-commerce platform Xianyu, tomb-sweepers are available for between 300 and 600 yuan. “You need to reserve earlier, professional tomb sweepers are extremely busy during Qingming Festival,” a tomb-sweeping agency manager told TWOC five days before this year’s Qingming Festival. “We also have staff who can play sorrowful music on the violin and hulusi [a traditional Chinese flute], but the price of hiring them is higher.”

The hired tomb sweepers livestream their work, so clients can follow along as they clean the tombstone, read the customer’s eulogy, and burn paper money as offerings to the deceased. Different packages are available: some include music requested by the customer, or laying flowers on the site.

While burning joss paper and gold ingots for the dead remains a common tradition to provide resources in the afterlife, now the departed need modern comforts too: paper smartphones, headphones, smartwatches, and even Wi-Fi routers. People can even buy flammable plane tickets, passports, visas, and insurance for the deceased who want to travel even in the afterlife. These “Hell Passports,” issued by Yama, the king of hell in Chinese mythology, are available on Taobao for just 5 yuan.

Burning these objects and large paper wreaths is common, but the smouldering makes for smoggy air. Many cities in China have banned open fires for safety and pollution reduction, so merchants have adapted by selling electronic wreaths that cannot be burned but display customizable messages on a screen instead.

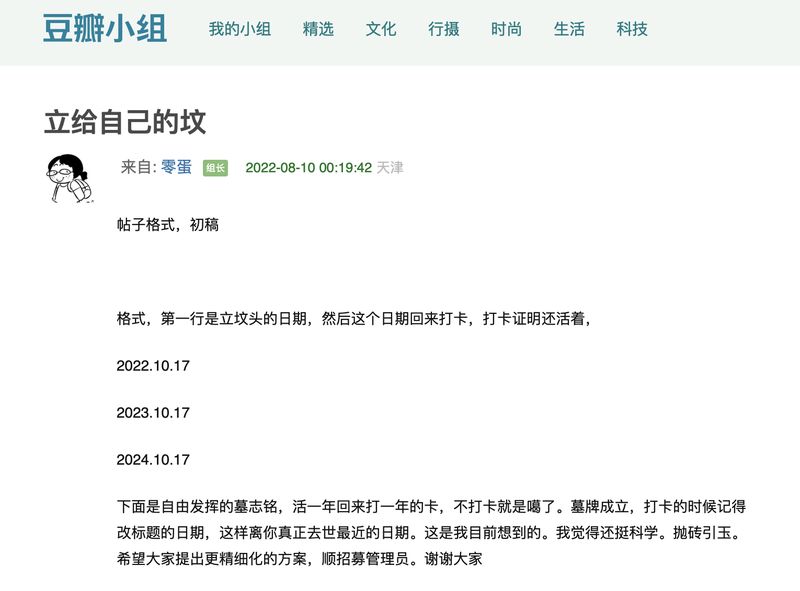

Some people have moved their remembrance totally online. On the social media and review platform Douban, netizens established an “online cemetery” to remember the accounts of owners who have passed away. Group members add a page (a “digital tombstone”) and a link to the dead user’s account. One page details a person’s life-long battle against cancer, while another pays tribute to a woman who spent years rescuing stray cats and dogs before she died. Under these posts, users leave comments of remembrance, share books and movies related to the tombstone owner’s life, and send flower emojis around Qingming Festival.

On Weibo, too, the accounts of deceased individuals often become places of remembrance. The Weibo account of Li Wenliang, a doctor who tried to alert authorities to Covid-19 in Wuhan as early as December 30, 2019, and who was later heralded as a hero, has been flooded with well-wishes and messages of solidarity since his death from the virus in February 2020.

Many living users also set up digital tombstones, so they can leave something behind when they die. Often they don’t have family to organize an offline burial for them. These users set up an account with a self-introduction, then update it each year with a time stamp to show their followers they are still alive. If the time isn’t updated, it means they have passed away.

These digital cemeteries can be sad corners of the internet, but many netizens find solace in their shared experiences with the deceased or strength in other’s struggles. They often write comments as if talking to a living person—these people always listen.

“The death of a person should not be regarded as the end of our connection with them,” says Lu Gang. He is considering updating his QR codes with technology that can produce a 3D image of his father, so people can remember him even more clearly. “After all, death is not the end, forgetting is.”