How tattoo artists stay creative amid economic pressures, and try to make sense of their pandemic experiences through ink

On a chilly January day on the 12th floor of a plain residential high-rise in southeast Chengdu, Sichuan province, a man is doing his best to bear the pain of receiving a giant tattoo of a thistle on his chest.

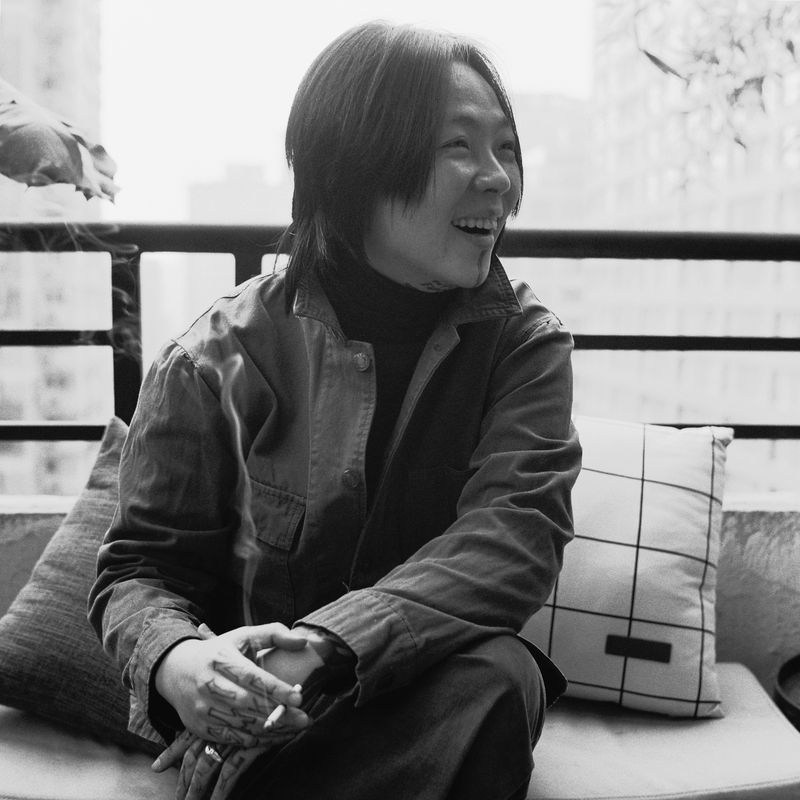

“We’re really in the business of selling pain,” chuckles Li Manman, the co-founder of Temple Tattoo. “And after the numbing experience of the last three years, people may want the pain to feel alive again.”

At another workstation inside the three-story tattoo parlor, 64-year-old Li Wenhui is getting ready for her first tattoo: a mandala-inspired pattern on her back. “We just need beauty in our lives, no matter our age,” she tells TWOC, oblivious to the many challenges those tasked with creating that beauty are facing—like finding the mental space necessary for creative work under financial pressure, especially during the pandemic.

Manman founded the tattoo parlor with a close friend and business partner in 2017. It now attracts not only customers young and old, male and female, but also tattoo artists lured by the promise of space to create, rather than struggling to make ends meet. Unlike the many traditional studios where the artist is usually also the business owner and manager, Temple operates under a salon model where tattooists are paid commissions and the parlor takes care of logistics like marketing, bookings, and supplies so the tattooists can (in theory) be free to focus on the art.

After the lean pandemic years, with lockdowns and other restrictions damping Temple’s revenue, the parlor is one of many businesses enjoying renewed vitality as the economy opens up. While many Chengdu parlors went under during the pandemic, Temple is now one of the larger studios in a city with a considerable scene—the city had over 500 parlors before the pandemic, now down to around 200, estimates a tattooist from another parlor.

During the pandemic, Manman, who is not a tattooist herself, lived off savings for months around the time Chengdu was locked down in September 2022. Many of the tattooists-in-residence now at Temple faced similar challenges: “To work alone was quite challenging for me,” says Jiran, a 30-year-old tattooist from Guangxi who has been tattooing since around 2012, and ran her own business out of her apartment until 2021, when she began to struggle due to Covid restrictions. “I was charging too little money alone. All I wanted was to make good works, not money.” Since joining the parlor in 2021, Jiran claims she has a more stable stream of customers and income, even though she’s not paid a base salary.

Temple charges customers an hourly flat fee of around 1,200 yuan, up from 800 yuan when the parlor first opened, but the studio takes a cut of 50 percent, leaving the remainder to the tattooists. Manman and Santong, Temple’s general manager, take care of finding, filtering, and forwarding new clients, as well as providing aftercare once the tattoos are done, including taking visual records of completed works.

“We give the artists the space they need to be creative and take care of everything outside of the tattoo work,” Santong tells TWOC. For Anuo, a 32-year-old tattoo artist who joined Temple in 2021, this has been true: She used to run her own tattoo business in Chengdu, but financial pressure during the pandemic forced her to move back to her hometown of Yiwu, Zhejiang province, where she received financial support from her family while taking tattoo gigs for local clients.

There, she says, she often had to compromise her artistic principles to make money, as she claims many customers wanted her to ink designs she viewed as tasteless or unwise (think a girlfriend’s name on a heart). Sometimes she would reject their requests, often facing abuse in return: “You have no idea how many customers in Yiwu ended up blocking me on WeChat,” she tells TWOC.

Anuo takes her work seriously: “My job as a tattooist is to uncover what the person really desires, because they’ll have it for the rest of their lives,” she says. “We create new skin, that’s god’s job…we need to be careful and responsible with that,” she adds with a laugh, “But if you have bills to pay, you end up doing something you don’t want…and once you go down that road, you never come back, because it’s easy money.”

At Temple, the resident artists are still expected to bring in their own customers. The studio can’t guarantee there are always clients, or that the work is always creative. “If there is a lack of customers, we try to find some commercial work for the artists to do,” explains Manman. Subject to some seasonal variation, the tattooists can expect to take home between 13,000 and 16,000 yuan per month on average, she claims, based on numbers from last year, far higher than the average salary in Chengdu of 7,654 yuan per month in 2021.

“I used to be in the military, you know,” Li Wenhui explains as the tattooist skillfully moves the tattoo gun across her skin. “The only tattoos I remember back in the day were some small symbols conscripts from the countryside sometimes had on the back of their hands, probably made by their family in the village to identify them in case they got lost.”

Confucian teachings traditionally forbade damaging one’s own body, as it came from one’s parents, and tattoos on one‘s face were a form of punishment for convicts as early as the Zhou dynasty (1046 - 221 BCE). However, tattoos had become fashionable among lower classes by the Tang dynasty, with folktales and records showing hooligans, prostitutes, and servants inking pictures and poems onto their skin, and tattooists working in public markets. In the 20th century, the first commercial tattoo parlor opened in Hong Kong in 1946, and early mainland tattooists like Yang Zhuo, who became one of the first to exhibit abroad in the early 2000s, have said they were inspired to get tattoos by rock musicians from the West in the 1980s.

Tattoos still bear the stigma of deviance and association with criminal gangs in parts of Chinese society. Athletes have been required to cover up their tattoos to play in sports matches, and authorities have banned tattoos from being shown on TV due to their concerns about “influence” on the country’s youths. “These days I believe you’re not allowed to have any tattoos in the military,” says Li Wenhui.

Since the pandemic, however, the customers who find their way to Temple—men and women in roughly equal numbers, Manman says—now seem to be more determined about getting tattoos compared to before. “The oppressive atmosphere and loss of control during the pandemic may have set free a stronger desire for self-determination and self-expression,” she reasons, sharing an anecdote about a client who brought in his fiancée to get wedding rings tattooed on their fingers. “We don’t typically do this kind of capricious commercial work, but his fiancée was a frontline medical worker during the pandemic and got seriously ill at one point, so they decided to get married and have their wedding rings tattooed.”

Li Wenhui’s tattooist Zhendong, born in Xichang, Sichuan province, has been in the scene since around 2014—first doing old-school work, meaning flatter, more traditional designs without much shading and detail. But after visiting a tattoo convention in Hong Kong a few years ago, Zhendong began exploring dotwork—the technique of inking a series of dots to create images—and mandala-inspired symmetrical designs like the one he made for Li.

The 33-year-old is continuing to innovate as the times change. As Li heads downstairs to have pictures taken of the now-finished tattoo on her back, Zhendong describes to TWOC how three years under China’s “dynamic zero” Covid strategy, with endless PCR testing and other strict containment measures, impacted his designs. He has recently been exploring bio-mechanical works, the kind of designs that combine his hallmark mandala-inspired symmetrical shapes with H. R. Giger-esque aesthetics of bio-machine hybrid entities. “Perhaps this is my way of venting my feelings,” he says while showing off recent works on his phone. “I think what interests me most is the connection between the tattoo and the shape of the body.”

As clients like Li leave with new artworks on their bodies, newcomers make their way to the converted apartment, sit down on the sofa in the reception room, and start flicking through some of the artists’ previous works. Like many customers Manman has observed recently, it doesn’t take long for them to make an appointment. And as long as there’s demand for “pain,” to feel more alive again or for whatever reason, the artists at Temple Tattoo seem well equipped to supply it.

Photography by Roman Kierst