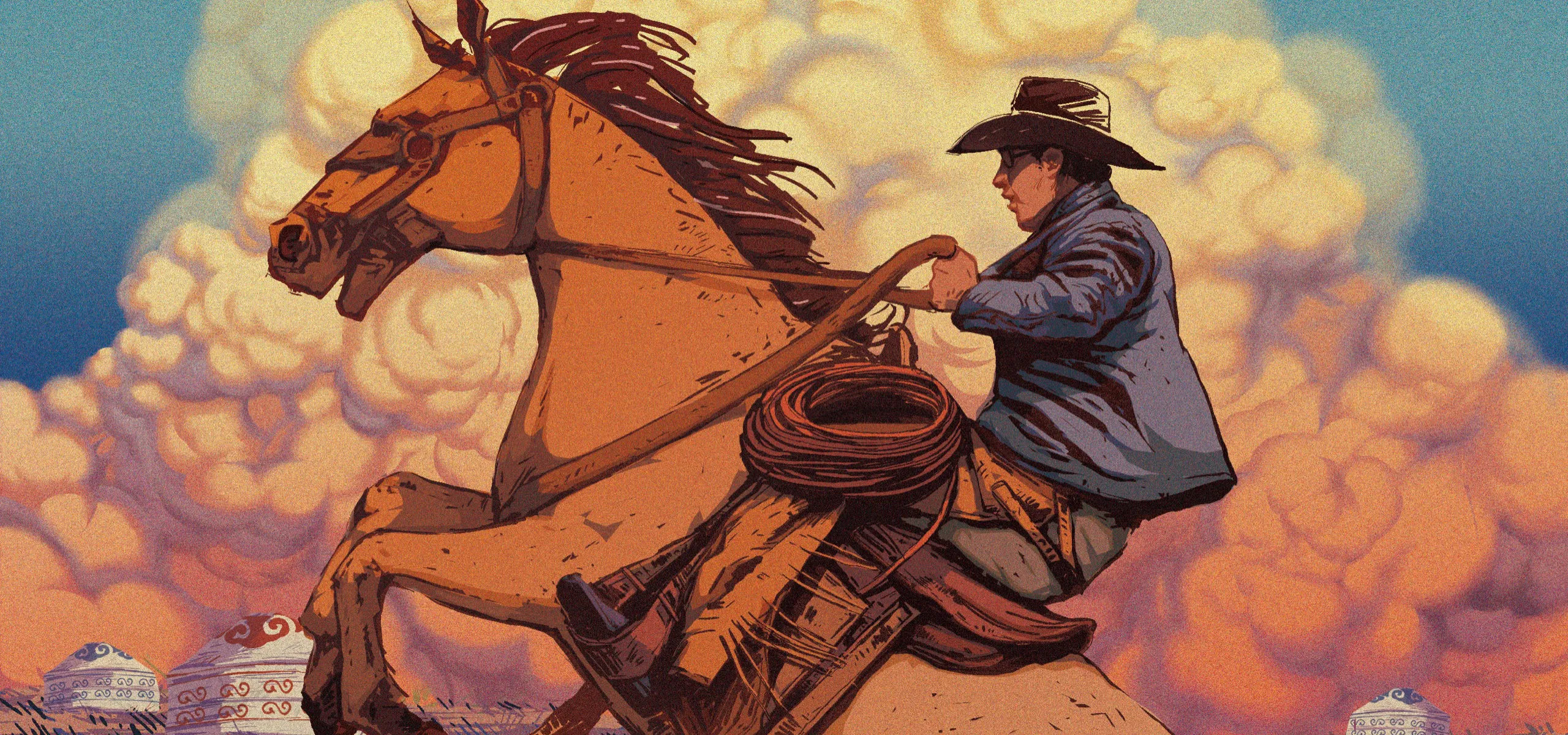

Modern “cowboys” embrace the steppes of northern Hebei province as a rural escape

As we get clear of the streets of Xiaobazi, a dusty town in northern China’s Hebei province, my companions and I urge our horses into a trot, then a canter, and then, with the barest prompting, a full-blown gallop. I grip my horse’s middle as tightly as possible with my legs as we tear forward, keeping just enough of a hold to convince myself that I’m in control.

As I fall into the rhythm and let myself feel the thrill of the dry wind battering my face, I become aware of a mechanical roaring to my left, just behind me but quickly drawing level. Haohao leans out of the window and whoops at me, with other voices swelling the chorus from the darkness of the SUV’s interior.

As it turns out, the SUV isn’t just following us for the thrill of the speed. The whole thing is being filmed by Haohao, an elementary school teacher from Beijing who comes here every week to live the life of a cowboy—minus the herding, the manure-shoveling, and all the other boring parts.

Within a couple of hours, I find that I’m part of a slick video the group has posted on the Chinese short-video app Douyin, replete with slow-motion galloping, trick jumps onto the bare backs of horses, and a shot of Haohao wearing low-slung denim shorts that show her midriff. Her high leather boots look like they chafe painfully on the legs, but get a murmur of approval from the men who have gathered around to watch as we discuss the day’s ride in the makeshift tavern some of the locals have set up to sell tea and snacks to saddle-sore riders.

In Xiaobazi, located in the Bashang Grasslands over 100 kilometers north of Beijing, every wall is painted with primary-color murals of Mongolian horse-lords in heroic poses: drawing bows at full gallop, or surveying the plains with hunting falcons perched on their gloved fists.

Among the real-life riders, though, there is not a single steppe warrior in sight. Instead, most are urban professionals in early middle age, dressed in the exotic garb of a land over 10,000 kilometers away: Texas. “It’s mainly because it’s more practical,” says Xiaolin, a 40-year-old rider who owns an electronics store in Beijing. “We like the colors of [American] cowboy costumes, and Mongol clothing is kind of drab.”

Like many other leisure activities, horse riding has taken off significantly in China over the last decade. Between 2017 and 2019, the number of riding clubs in China doubled from 900 to over 1,800. Upscale riding clubs in Shanghai, like the Country Down Club, charge annual membership fees equivalent to 8,400 USD and cultivate an elitist image.

Xiaobazi, however, caters to the lower end of the market. Bashang, which covers an area of some 16,000 square kilometers, is the nearest grassland to Beijing and was once the exclusive hunting ground for emperors of the Qing dynasty (1616 – 1911).

Most of the people who come to Xiaobazi and other villages in the Fengning Manchu Autonomous County are from either Beijing or Hebei. But some come from farther afield, like the woman from Shanghai who said she preferred Xiaobazi’s rustic setting to the country clubs closer to home. Few visitors grew up around horses, and most learned to ride by coming to the village on the weekends instead of taking formal classes.

In recent years, tourism has become Xiaobazi’s main industry, with many of the locals employed as hotel workers, guides, or horse grooms. During an early afternoon ride to a hamlet about 10 kilometers away, we stop at a farm housing a grinning middle-aged couple who have converted their kitchen into an informal restaurant for hungry travelers.

Most people in Xiaobazi are Manchu, but speak standard Mandarin to each other as the Manchu language is now virtually extinct. Most of the homes in the village lie empty and dilapidated, with nature reclaiming the brick farmhouses after their former residents moved to the town in pursuit of better jobs and housing. There are no plans to bring running water to the village, and cattle-grazing on the hillsides is heavily regulated to protect the land.

The riders with me have met many times before on previous visits. When we sit down for lunch the following day, some of them strip off bits of clothing to show their war wounds. Haohao pulls down the collar of her shirt, revealing a nasty-looking scar on her right shoulder where she broke her collarbone falling off her horse while racing a friend.

Most longtime riders have the scars to prove it, but generally say they all started riding again as soon as they recovered from their injuries. Their horses, however, are not always so lucky. Several years ago, my companions tell me, a new rider lost control of his rented steed and collided with another horse. While both riders escaped serious injury, both of the animals died in the incident.

Some of the riders stable their own horses in local farms, and a rider named Taiwei has bought over a horse called Baitui (“White Legs”) in a trailer. You can guess the physical features of just about every horse here by its name—“Big Black,” “Small Brown.” He tells me that one day he hopes to move out to be near a place where he can ride more frequently, instead of driving out here every weekend.

None of the riders are competitive equestrians, but they sometimes race informally against one another. More commonly, they take their horses out for daylong expeditions, changing the pace as the mood takes them—a leisurely walk one minute, and then a sudden, explosive gallop.

They stress that this distinguishes their approach from competitive riding and other outdoor sports. “If you think of badminton or cycling, for example, they’re all about the interaction between you and an object,” Xiaolin says. “With a horse, it’s different. If you get along with the animal, you can have real communication with it.”

Perhaps the most striking thing about people like Xiaolin is their lack of cynicism. Despite riding’s association with the great outdoors, northern Hebei is hardly an untamed wilderness, if it ever was—the steppe was arguably as much a managed ecosystem as any agricultural zone, and Bashang was right in the heartland of powerful dynastic states like the Northern Wei (386 – 534) and Liao (907 – 1125).

Today’s riders range in the shadows of windfarms and neatly ordered tree plantations, and visitors dreaming of unspoiled grasslands sometimes fall victim to modern “bandits”: unscrupulous tour operators and locals who charge exorbitant sums to trot around a paddock and stay in cheap imitations of Mongolian yurts.

Still, many riders say they are embracing a different kind of life away from the stress of the modern economy, one in which they find greater meaning through their relationships with horses. Their thirst for freedom and rugged individuality is partly a performance, symbolized by their garb inspired by the American West, their use of American-style saddles rather than high-backed Mongolian ones, and their American-style seat with the heels pointed outward. “Obviously, horse riding is about you and the horse, but in a place like the grasslands, dressing up like this shows that it’s also about being in the wilderness,” says Taiwei.

Haohao posts a photo to her profile on WeChat, China’s near-ubiquitous social messaging app, showing her riding at a gallop. Underneath, she writes: “Women who ride horses are usually liberated and independent, wishing to be free and unconstrained. Riding on the back of a good horse is a feeling of not being inferior to any man.”

Taiwei says he hopes more people will take up riding as a means to commune with nature. “I can’t really say what the future holds for horse riding, but I can tell you this…, riding horses is a skill you can cultivate, and you can get better at riding horses, but having this kind of relationship with the animal will also make you a better person.”

Saddle Up: Riding with China’s New “Cowboys” is a story from our issue, “Upstaged.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.