Spice up your Chinese conversations with a sprinkling of red song lyrics

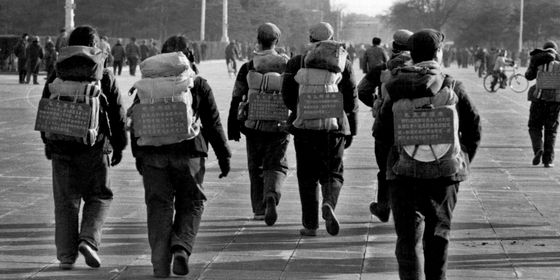

Stroll through a Chinese park of a morning and you are likely to catch strains of music and singing floating through the air. Draw closer and you’ll find the choir consists of benign-looking silver-haired old folk, sitting or standing with their hands clasped behind their backs, belting out chorus after chorus of what sound like uplifting power ballads. What are they singing? In most cases, the track list will contain a healthy selection of red songs (红歌 hóng gē), a vocal legacy of China’s recent past.

Red songs are most often associated with the patriotic or propaganda tunes written between the 1940s and 1978. The genre still survives, but without the kind of impersonal dedication that pervaded the music in former decades, and consequently missing the essential ingredient necessary to be considered a true red song.

In the 1950s, war movies carried scores almost exclusively consisting of red songs, while their other primary preserve were tracks extolling the virtues of the redoubtable Chinese worker and his struggle to build the new China.

In the 1960s, red songs based around the theme of how much people loved and worshipped Chairman Mao became de rigueur, and many composed in the latter half of the Cultural Revolution simply lifted Mao’s quotes and used them as lyrics. The artistic merit of the songs’ words notwithstanding, the tunes were so harsh on the ear that the style was immediately discontinued at the end of the Cultural Revolution.

Political notions aside, not all revolutionary songs are entirely devoid of musical merit—in fact, the musical quality of red songs is a major reason they’ve endured. The most celebrated red songs are invariably those that took classic minority compositions and replaced the original lyrics, or those that were composed based on established folk music styles. It’s often the ethnic charm, rather than the political overtones, that give red songs such wide appeal.

In 2009, red songs made a grand comeback among young people with the rise to stardom of 20-year-old folk talent Huang Ying (黄英), who won third place in “Super Girl,” the enormously popular Hunan TV reality show. Huang performed an almost entirely red repertoire on the show, sealing her fame as “the red song queen” with her rendition of the Jiangxi folk music number “Azalea” (《映山红》Yìngshānhóng), which essentially trumpets the people’s love for the Red Army.

Parodies of classic red songs with lyrics like “I fear no heaven or earth, but I do fear foreigners who can speak Chinese,” have made the tunes a source of comedy for a new generation.

Red songs frequently also employ idyllic depictions of China’s landscapes to pluck people’s patriotic heartstrings. In doing so, they serve as a testament to the tremendous changes China’s natural environment has undergone over the course of half a century. For example, “Waves after Waves in Honghu Lake” (《洪湖水,浪打浪》Hónghú shuǐ, Làngdǎ làng) begins with the lyric, “In Honghu Lake waves chase each other… you can see wild ducks, water chestnuts and lotuses everywhere.”

(洪湖水呀,浪呀嘛浪打浪啊……四处野鸭和菱藕。Hónghú shuǐ ya, làng ya ma làngdǎ làng a……Sìchù yěyā hé líng ǒu.) Fast-forward to the summer of 2011, and the worst drought in 70 years had virtually sucked the vast lake dry.

In 2010, red songs hit the headlines when it emerged that a Sichuan asylum was treating patients’ mental illnesses by uniting them in rousing renditions of the old classics, triggering public concern over the motivations behind (and effectiveness of) the therapy.

However, a Southern Weekly journalist visited the institution and came to the conclusion that the patients were mostly veterans who actually enjoyed the singing, and it was the only thing they could all do together. This hints at a primary reason why people are so attached to the songs: they represent a form of shared memory that is still strong enough to bring strangers together in parks.

Younger generations still find time for red songs, in part because the dramatic nature of the lyrics lend themselves well to comic interpretation, especially when dropped into conversations out of context. For foreigners, they’re also a means of flaunting your familiarity with Chinese culture, a la Youku phenomenon Hong Laowai (红老外), a New York-based American professional whose videos of himself singing red songs and other classics have garnered millions of views.

Current events and popular culture, like Steve Jobs and China’s voracious appetite for Apple products, often show up in red song parodies online.

Is your office beset by constant infighting and an air of perpetual gloom? Try boosting team spirit among your colleagues by declaring, “When united we are strong.” (团结就是力量。Tuánjié jiùshì lìliàng.) It’s a surefire red classic—if you learn only one red song, then this should be it. It was composed as early as 1943 for the purpose of pumping up people’s spirits for the war against the Japanese, and its elegant simplicity and rousing lyrics ensure it’s often used to open red song concerts (红歌会). Here’s the full stanza, guaranteed to rouse your workmates from their apathy if sung in full voice every Monday morning around the water cooler:

“When united we are strong! When united we are strong!

The strength is iron, the strength is steel.

But it’s stronger than iron, and harder than steel!”

Tuánjié jiùshì lìliàng, tuánjié jiùshì lìliàng!

Zhè lìliàng shì tiě, zhè lìliàng shì gāng.

Bǐ tiě hái yìng, bǐ gāng hái qiáng!

团结就是力量,团结就是力量!

这力量是铁,这力量是钢。

比铁还硬,比钢还强!

Have you finally quit a job that was driving you crazy? Or your boyfriend has decided to help out with the housework for the first time in his life, or you’ve just finished an excruciating project that seemed like it would never end? This one is perfect for celebrating the sudden relief of prolonged repression (but is probably best not applied to bedroom environments): “The liberated serfs are singing songs.” (翻身农奴把歌唱。F`nsh8n n5ngn% b2 g8 ch3ng.) The song was composed for a documentary made by the Chinese government in 1961 called “Tibet Today.” It assumes the voice of a Tibetan woman casting her eyes over the plateau and singing, “The liberated serfs are singing songs, the voice of happiness reaches the four corners of the nation.”

(翻身农奴把歌唱,幸福的歌声传四方。Fānshēn nóngnú bǎ gēchàng, xìngfú de gēshēng chuán sìfāng.) Try making your own variations like the following:

I finally quit that nasty job. I feel like a liberated serf singing songs!

Zhōngyú cí diào nà fèn tǎoyàn de gōngzuòle, zán fānshēn nóngnú yě bǎ gēchàng a!

终于辞掉那份讨厌的工作了,咱翻身农奴也把歌唱啊!

The project is finally over. Let’s go to KTV and sing like serfs to celebrate!

Zhège xiàngmù zhōngyú jiéshùle, wǒmen fānshēn nóngnú bǎ gēchàng, qù KTV qìngzhù ba!

这个项目终于结束了,我们翻身农奴把歌唱,去KTV庆祝吧!

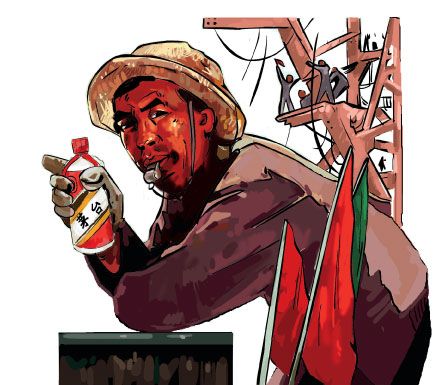

“I Produce Oil for My Motherland” became “I Drink Moutai for My Motherland” after Sinopec was found to have spent RMB168 million on the pricey booze.

In 1960, China discovered the Daqing oil field in Heilongjiang Province, the country’s largest crude reserve. Previously, oil had been considered a scarce resource and buses were powered by gas tanks attached to their roofs, so to celebrate the momentous effort of the oil workers, “I Produce Oil for My Motherland”

(《我为祖国献石油》Wǒ Wèi Zǔguó Xiàn Shíyóu) was composed in 1964 and became another instant red classic. It’s full of heroic exhortations, but the best known lyrics are “I fear no heaven or earth, come wind, rain, thunder or lightning.” (天不怕,地不怕,风雨雷电任随他。Tiān bùpà, dì bùpà, fēngyǔ léidiàn rèn suí tā.) Chinese netizens have added their own twists to the line:

I fear no heaven or earth, but I do fear well-educated hooligans. (The term refers to well-read but corrupt officials.)

Tiān bùpà, dì bùpà, jiù pà liúmáng yǒu wénhuà.

天不怕,地不怕,就怕流氓有文化。

I fear no heaven or earth, but I do fear Sichuan people who speak Mandarin. (Sichuan people’s accents ensure they’re often tough to understand when speaking Putonghua.)

Tiān bùpà, dì bùpà, jiù pà sìchuān rén jiǎng pǔtōnghuà.

天不怕,地不怕,就怕四川人讲普通话。

I fear no heaven or earth, but I do fear foreigners who can speak Chinese.

Tiān bùpà, dì bùpà, jiù pà lǎowài huì jiǎng zhōngguó huà.

天不怕,地不怕,就怕老外会讲中国话。

The title of the song also leaves itself open to a number of ironic variations. In 2011, oil giant Sinopec was exposed as having spent RMB168 million on Moutai liquor and then couldn’t explain how they had disposed of the order, after which a music video entitled “I Drink Moutai for My Motherland” (我为祖国喝茅台 Wǒ Wèi Zǔguó Hē Máotái) appeared on Youku. As there are no official PM2.5 statistics (a designation for measuring air pollution) released in China, citizens in heavily polluted cities began performing their own tests, merrily declaring, “I test the air for my motherland.” (我为祖国测空气。Wǒ Wèi Zǔguó Cè Kōngqì.)

In 1966, a magnitude seven earthquake struck Xingtai, Hebei Province. As usual, the government’s sterling relief efforts were immortalized in song, this one with a suitably long and impressive title: “The Sky is Vast, the Earth is Vast, but Neither is as Vast as the Party’s Great Kindness.” The lyrics are worthy of re-publishing in full:

The sky is vast, the earth is vast, but neither is as vast as the Party’s great kindness.

Dad is dear and mom is dear, but neither is as dear as Chairman Mao.

There are a thousand good things out there, maybe 10,000, but none as good as socialism.

The river is deep, the ocean is deep, but neither is as deep as class solidarity.

Tiān dàdì dà bùrú dǎng de ēnqíng dà,

Diē qīn niang qīn bùrú máo zhǔxí qīn.

Qiān hǎo wàn hǎo bùrú shèhuì zhǔyì hǎo,

Hé shēnhǎi shēn bùrú jiējí yǒu’ài shēn.

天大地大不如党的恩情大,

爹亲娘亲不如毛主席亲。

千好万好不如社会主义好,

河深海深不如阶级友爱深。

The first two lines are, for perhaps obvious reasons, most frequently the subject of parody. Deploy them when you want to highlight something’s importance:

The sky is vast, the earth is vast, but neither is as great as having something to eat for lunch.

Tiān dàdì dà bùrú chī wǔfàn de wèntí dà.

天大地大不如吃午饭的问题大。

Dad is dear, and mom is dear, but neither is as dear as Steve Jobs. (This appeared as the head of a post satirizing the popularity of Apple products in China.)

Diē qīn niang qīn bùrú qiáobùsī qīn.

爹亲娘亲不如乔布斯亲。

Yet in spite of such jokey imitations, when it came to the 90th anniversary of the founding of the Chinese Communist Party in 2009, a red song renaissance targeting students in particular rolled out nationwide. With a new generation inducted, the original, emotive tunes will likely remain in the national songbook for some time to come.