Give China’s apocalyptic, mutant viruses a chance

The end, as it happens, is nigh: “Chinese Scientists Create New Mutant Birdflu”, “Made-in-China Killer Flu Virus”, “Chinese Scientists Face Ethical Scrutiny After Creating New Strains of Potentially Deadly Virus”. An article in the British newspaper The Independent put a controversial scientific paper in the spotlight, with senior scientists accusing China’s researchers of “appalling irresponsibility.”

Professor Lord May of Oxford told The Independent, “They claim they are doing this to help develop vaccines and such like. In fact the real reason is that they are driven by blind ambition with no common sense whatsoever.” As a respected member of the Royal Society, people listen when Lord May talks, but China’s research into various influenza viruses has the potential to protect the world from pandemics, or, at the very least, learn more about deadly viruses.

With that in mind, China’s research is raising serious questions. Is it ethical to create potentially lethal viruses to fight future strains? Does China have the wherewithal in biosecurity to keep their new viruses locked up?

While the news cycle on which this topic spun is now over, the controversy is far from over, and it is important to remember that, behind the kerfuffle, groundbreaking research is pioneering new paths to vaccines. In order to do that, ethics get shifted and headlines get thrown around. But, as is so often the case with science stories, readers are left wondering what’s next.

Not With a Bang, but with the Flu

The debate stems from “H5N1 Hybrid Viruses Bearing 2009/H1N1 Virus Genes Transmit in Guinea Pigs by Respiratory Droplet”.

The study, in its own words, says, “If these mammalian-transmissible H5N1 viruses are generated in nature, a pandemic will be highly likely.” But, that, surprisingly, wasn’t the shocking part. The research methodology involved 127 reassortants, also known as hybrid viruses. By changing a single gene in H5N1 and H1N1 viruses, it was possible for the bug to jump from guinea pig to guinea pig.

Guinea pigs, according to one of the lead researchers, have both avian-like and human-like receptors in the respiratory tracts, making them ideal for study. The research took two years, 250 guinea pigs, 1,000 mice, and 27,000 infected chicken eggs. The sheer scale of the methodology—of 127 new viruses, one capable of passing between mammals—put the paper in the spotlight.

While plasmid-based reverse genetics is far from new, changing viruses to be more deadly and infectious with little practical application is—according to some—on shaky ethical ground. The experiments themselves are key to understanding flu viruses’ most basic structures and how they can evolve. However, the magnitude of the research being conducted in China is staggering, not to mention successful.

The voluntary moratorium on this practice ended in January of this year, but the work at the National Avian Influenza Reference Laboratory at Harbin Veterinary Research Institute in China was a groundbreaking—some would say irresponsible—advancement with wide-ranging implications. The two main concerns about the research are that, as it disseminates, it could be used as a weapon and that containment procedures are not sufficient. It being used as a weapon is largely handwringing, but, as China rapidly amps up its scientific research budget every year, biosecurity could potentially be a real threat.

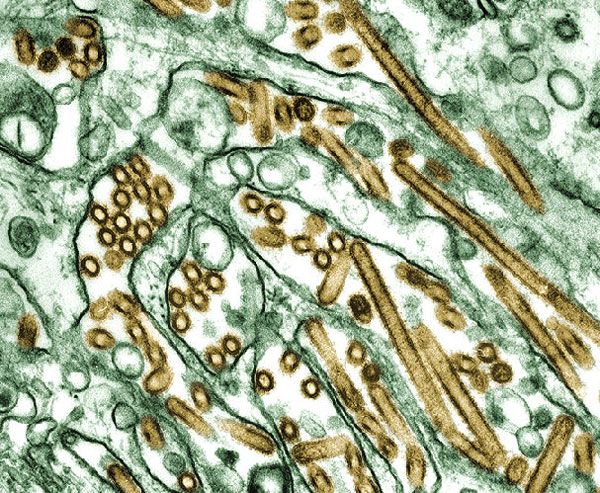

An electron micrograph of the H5N1 bird flu virus

Alan P. Zelicoff from the Institute of Biosecurity says that while Biosecurity level 3 (BSL-3) is perfectly adequate, “There is always concern regarding the creation—either in nature or in the laboratory—of new influenza reassortants.” The Harbin Veterinary Research Institute does indeed have BSL-3, an extremely safe level, but, considering what is at risk, is that enough?

BSL-3 involves controlled access to laboratories, protective equipment, air filtration, sewage decontamination, personnel showers upon exit, and testing of facility integrity. Daniel Perez from the University of Maryland says in his article, “H5N1 Debates: Hung Up on the Wrong Questions” that, “No containment condition is fail-proof.” Perez also states that variant vaccines and further research are key in preventing future pandemics.

The ever critical Lord May said in his original statements that, “The record of containment in labs like this is not reassuring. They are taking it upon themselves to create human-to-human transmission of very dangerous viruses.” Some sited China’s lack of containment effectiveness directly. There’s no denying that China is closing the research gap with the USA, but a lack of transparency has a tendency to breed suspicion.

However, while headlines claimed the world’s scientific community was solidly against this sort of research, complete with apocalyptic headlines, not everyone agreed. In fact, many support and encourage this sort of research.

Li Zejun at the Department of Avian Infectious Diseases at the Shanghai Veterinary Research Institute (SHVRI) says, “It’s scientific research, and it shouldn’t be made into media hype.”

Moreover, Professor Li Gang of the Institute of Animal Sciences (IAS), at the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CAAS), thinks the publicity surrounding containment is nothing but bluster: “It is perfectly feasible as the research was undertaken with complete biological safety in the laboratory with high security grades and applicable research qualifications.”

However, some are left wondering if China, with a lack of international oversight, can ensure the safety of this BSL-3 lab. But, Harbin’s lab is not just qualified, it is exemplary. Two months before the May study was published, the Harbin laboratory was named a Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), an international honor for a lab. China’s Chief Veterinary Officer, Yu Kangzheng said at the plaque unveiling ceremony that they and the FAO had cooperated in areas such as animal disease control and biosecruity.

With that in mind, if biosecurity offers any security at all, the lab in Harbin should raise no alarms. It seems as though at least some of the questions raised by eminent scientists were motivated by misunderstandings or ethical misgivings regarding the methodology, but that doesn’t mean criticism is groundless.

Though in this case it seems censure was unfounded, the ethical implications for coming up with potential vaccines and designing precarious viruses is a serious topic that will likely never end. It is a matter of weighing the risks, but, for the time being, it seems the scales rest in Harbin.

Amid the condemnations, many scientists battened down the hatches and rushed to the defense of the project, specifically the project’s leader.

The Brains behind the Bugs

The brains behind the research belong to Chen Hualan who works with the Harbin Veterinary Research Institute with an 80 plus team of dedicated personnel who want to save the world from avian flu pandemics.

Chen is a giant in her field, respected beyond reproach. From a small city in poor Gansu Province, she choked on her college entrance examination, and, instead of studying medicine, went into veterinary science. When she first arrived at Harbin Veterinary Research Institute she was told to study influenza by her supervisor, Yu Kangzhen. Since then, her rise—and the rise of avian flu—has been stunning.

In the early 90s, the equipment for studying viruses in China was far from contemporary. She spent three years in Atlanta’s CDC offices where she attempted to work with reverse genetics; this is where she had her first run in with the building blocks of hybrid viruses. Chen is known for her work ethic; as Science magazine said in a glowing profile of her in July, “Instead of waiting to obtain plasmids developed by other labs, Chen decided to make her own.”

The hard-working staff at the Guangxi Animal Disease Prevention and Control Center vaccinate chickens to prevent future outbreaks of H5N1 in April of 2013

With success in America, Chen’s decision to move back to China astounded her family, not to mention her resolution to study in the harsh, frozen landscape of Harbin Province. Her work there paved the way for bird flu vaccines.

Some defending Chen have done so vociferously, particularly Dr. Vincent Racaniello in “Influenza H5N1 x H1N1 Reassortants: Ignore the Headlines, it’s Good Science”. The professor at Columbia University said, “I believe that the news headlines depicting these experiments are irresponsible and dangerous are based on uninformed statements… I wonder if they even read the paper in its entirety before making their comments.”

Despite her reputation, prominent scientists like Professor Simon Wain-Hobson questioned the potential for Chen’s research in The Independent: “The virological basis of this work is not strong. It is of no use for vaccine development.”

This raises the question, is it really worth it?

Reasons for Reassortants

Theory and understanding are key in preventing dangerous viruses like H1N1 and H5N1. Li Zejun at SHVRI echoes this sentiment: “For prevention and control of flu, the more basic knowledge we have, the easier it will be for us to smother pandemics in the early stages in the future.”

Beyond theory, this type of research has incredible potential; Chen and her team have already garnered more than their fair share of success stories.

Chen’s team came up with an avian vaccine for the Newcastle disease in 2011, using reverse genetics to create recombinant NDV-based live virus-vectored vaccines; though rare, Newcastle disease can infect humans with flu-like symptoms.

More importantly, Chen’s team developed a vaccine for the H5N1 strain in birds, now used around the world. In fact, as of 2009, over 55 billion doses were used to control outbreaks. Advancements in the field have enabled researchers like Chen to develop vaccines before the strains arise in nature.

Part of the reason that China’s technology has skyrocketed in the area of avian influenza is the fact that East Asia faces a serious risk of outbreaks. In 2003 and 2004 outbreaks of H5N1 took lives in Thailand and Vietnam, with chickens and ducks in South China playing a role in spreading the disease.

Li Gang from the IAS says, “The research has theoretical properties in preventing and controlling the highly pathogenic avian influenza and provides theoretical evidence to research and develop new drugs and vaccines.”

While concern for security and containment are paramount, looking at future strains of viruses such as these may take precedence. Opponents of studying these viruses with Chen’s groundbreaking methodology are reasonably concerned about containment, but the consequences of not pursuing this research—being unprepared for an outbreak—could be even more dangerous.