Recent documentary shows officials who lie, cheat, and defraud their way to the top echelons

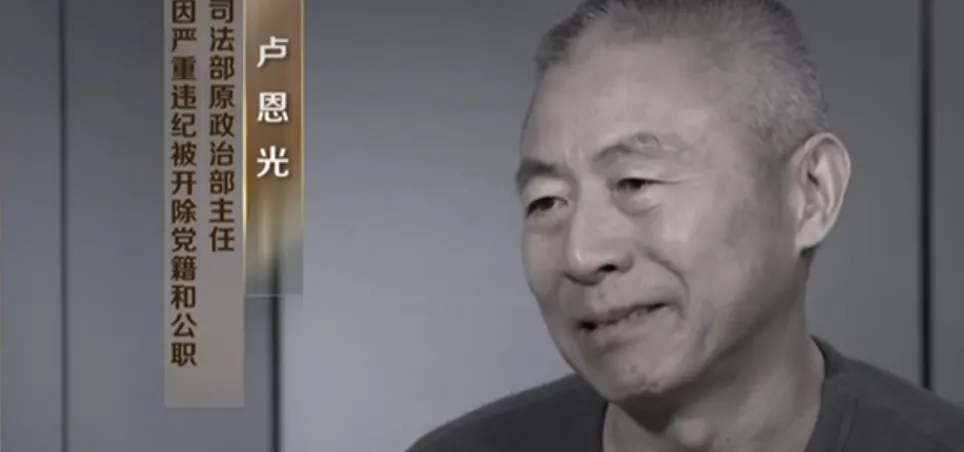

“I was so obsessed with being an official,” says Lu Enguang. “Looking back at the paths I walked over the last 20 years, it feels like a dream, a nightmare. I was crazy.” But Lu was seemingly crazy enough to survive two decades as a top official, before being exposed as a liar and scam artist. Now the former Ministry of Justice official’s confession forms part of a new CCTV documentary series on fallen officials, released to promote the government’s anti-corruption efforts in front of an important Party conference in October.

Of all the departments that Lu could have scammed his way to the top of, he chose one which was supposed to represent truth and integrity.

Ever since he was young, Lu had always had an entrepreneurial streak. In his home province of Shandong, he’d met with moderate success as owner of a glass factory, but his ambitions far outpaced the opportunities this afforded. In this, and his brazen misdeeds, he bears a resemblance to American conman Frank Abagnale, who shot to fame after being played by Leonardo DiCaprio in the 2002 film Catch Me If You Can.

Both men were brazen in the fraud they used to fabricate almost every detail of their lives. But in Lu’s case, the deception was supplemented with bribery.

In order to make his way into Chinese bureaucracy, Lu lied about when he had joined the Communist Party, backdating the year from 1992 to 1990. This rendered him instantly eligible for positions that required two years of membership, while also catapulting him past the probation period when checks on his background might have occurred.

Lu also falsified his age, making him seem seven years younger than he actually was—giving him an edge in getting promotions and avoiding retirement pressures.

There were other vast lies: In reality, Lu had seven children. Given China’s family planning regulations, this would have nixed his government career, so he declared that he had just two children, and instructed the rest to call him “uncle” at home.

These steps all improved his eligibility for the roles and promotions he wanted. But in order to actually make his way into the big leagues, Lu became legendary for his determination to give bribes to officials, and refuse to take no for an answer. Between 1997 and 2015, he shot up from a village official who worked in agricultural development, all the way to director of the political department in the Ministry of Justice.

Lu’s lies eventually caught up with him, after someone checking his original Party membership application, dated 1990, and found a reference to Deng Xiaoping’s famous “Southern Tour” of China—which took place two years later, in 1992. The anomaly aroused suspicion. This led to an investigation last December, which resulted in Lu’s firing from his official position in May for bribery, and loss of his Party membership.

The documentary series which charts this tale, 《巡视利剑》 (“Sharp Sword Inspection”), is a co-production by CCTV and the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI) to showcase the results of the anti-corruption drive within the Communist Party begun by General Secretary Xi Jinping at the 18th Party Congress in 2012. Four episodes, airing between September 7 and 11, describes the downfall of officials and directors of state-owned enterprises investigated by the CCDI. Apart from Lu, the series has featured Si Xianmin, the golf-addicted former CEO of China Southern Airlines, and Wang Baoan, former director of the National Bureau of Statistics expelled for bribery and nepotism.

The achievements of the anti-corruption drive are expected to be highlighted by the 19th Party Congress, which will begin on October 18.

Cover image from jsycjw.gov.cn