Red tape and reluctant tenants have closed some of China’s best historical buildings to the public

Norman Lee, a concert pianist from Hong Kong, once spent 25 years trying to move house. In 1991, on hearing that the province of Guangdong was inviting overseas Chinese to return and invest in the mainland by offering them the possibility of gaining back their ancestor’ real estate properties, Lee’s father arrived in the port city of Shantou to reclaim Xiang Yuan, the European villa that Lee’s grandfather built in 1928 after making his fortune in business.

There was just one problem: An enterprise called the Chousha Firm had been using the house for the last 43 years—first to run an embroidery factory, then to accommodate the Shantou Disciplinary Committee, then still later, to lease to businesses ranging from a preschool to a cafe. And the law wasn’t exactly clear on how to get them out.

In the years that followed, the Lee family’s struggle to evict the company would involve attempted lawsuits, and appeals to various provincial and municipal bureaus. Finally, the family paid 1.2 million RMB out of their own pocket to the company and 200,000 to the then-tenants, which they accepted as compensation for moving out in 2015. It was not until then that Lee, who had only ever seen pictures of the family home, had his first glimpse of Xiang Yuan.

“It was a junkyard; not a single piece of furniture was left in the house,” he told TWOC. “They had carved up the rooms, took out doors and walls…they replaced the marble tiles from Italy and Spain…the chandeliers were stolen. And the government did not feel it was their responsibility to fix it.” By then, Shantou natives themselves had forgotten who really owned the well-known city landmark, with a local TV report falsely describing it as an old bank. Lee would spend the next two years renovating the house on his own dime, before reopening Xiang Yuan in early 2017 as a piano museum and cultural center.

Workers remove the sign of the Beijing Youth Palace from Shouhuang Hall imperial temple in Jingshan Park in 2013, after 57 years’ occupation (VCG)

Yet given China’s famously fraught relationship with its historical monuments, the Lee family may have achieved the closest thing to a happy ending. By now, the story of China’s demolition-prone streets and courtyard homes is well known, but homes like Xiang Yuan usually stand apart from the decrepit old neighborhoods bulldozed for urban development. As places of architectural distinction or historical note, they are eligible to be declared “cultural relic conservation units” (文物保护单位) by state cultural heritage bureaus, a privilege they share with structures such as temples, old government buildings and foreign consulates, former imperial dwellings, and the homes of famous historical figures. They are technically protected from outright demolition—but a different set of political challenges could condemn them first.

In 2015, Kong Fanzhi, the just-retired director of the Beijing Municipal Administration of Cultural Heritage, made a bid to have “eviction of cultural relics” included in China’s 13th Five-Year Plan (2016 – 2020). Kong was a longtime critic of the “unreasonable” use of Beijing’s protected landmarks by enterprises and state-owned work units, and at the time of his proposal, the Beijing Gardening and Greening Bureau had just released a report that more than 100 of Beijing’s 423 still-existing historical gardens had been repurposed by various organizations as makeshift offices or dormitories and were not open to the public, in addition to all but one of more than 40 “princely mansions” (王府) in the city, former homes to imperial brothers and uncles.

The heritage administration had last estimated, in 2010, that 40 percent of Beijing’s conservation units were occupied, an improvement over 2005, when the figure had been close to 60 percent and the city’s government was just waking up to the problem. In the decades before, people across the city had been drying laundry on centuries-old pillars, frying rice beside priceless pagodas, replacing Buddhist altars with machinery, and—in the typical secretive fashion of Chinese work units (danwei)—getting guards to chase out curious passersby who’d come to peek at a landmark of historical value. “This is a cultural relic conservation unit, but there are no [more] relics inside,” staff at one unnamed historic site told Hong Kong’s Sing Tao Daily in 2005.

It was around this time that Kong joined with various other government departments to push for the complete removal of occupying organizations from Beijing’s heritage units, in the interest of protecting these landmarks from decay. In 2015, Kong told reporters at a press conference that 80 percent of national-level conservation units have completed evictions. Forty percent of municipal-level conservation units still had yet to, and there were “even more” at the district and county levels. Outside Beijing, no city or province’s heritage bureau appear to have kept as close a tally of occupied units; in cities like the Lee family’s Shantou, where significant portions of the population emigrated in the last century, their number is untold.

The city’s heritage administration refused TWOC’s request for comment on their progress or on future eviction deadlines. However, Beijing’s Xicheng and Dongcheng districts of set a goal to carry out evictions from a combined 32 conservation units by the fall of 2017. A variety of high-profile evictions in recent years—a high-end lounge from inside the Songzhu and Zhizhu temples, a wholesale market from the old National Mongolian and Tibetan School site in Xidan—have boosted the public’s awareness of the city’s project.

Evidently, removing “unreasonable” occupiers is easier said than done. The main issue, as Kong has described it in many interviews, is “a problem leftover from history.” This is a euphemism that can be applied to host of issues perceived to have stemmed from the dramatic upheavals of Chinese society over the last century—and the disarrayed, often contradictory sets of regulations and values they left behind.

The occupation of protected landmarks first began in the tumult of wars between the 1920s and 1940s. In the case of Xiang Yuan, as with many homes of overseas Chinese in China’s coastal communities, the owners had moved to Hong Kong in the 1920s. They’d agreed to lease the house to the textile firm in the 1930s, but as the family did not return to Shantou for another 50 years, the firm had simply stayed put.

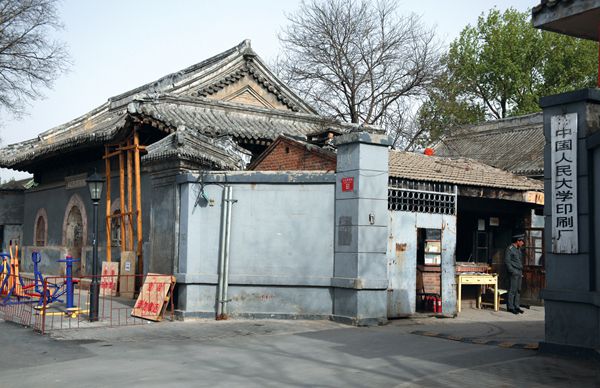

A wing of Nianhua Temple, formerly occupied by Renmin University Press, was destroyed in a fire in 2009 due to the illegal construction and trash on the grounds (VCG)

But while political instability had made these landmarks available, political unity—in particular, the demands of national rejuvenation after decades of war and revolution—was what accelerated their takeover. In the early years of the PRC, numerous danwei—schools, military organs, factories, research institutes, even workers’ “recreational palaces”—were being established across China to facilitate the top-down, modern Leninist state. Facilities were needed to house workers and serve their operations; abandoned buildings were a ready-made solution for a new nation strapped for money and time. Even the central government opted to move into the old imperial gardens beside the old palace, despite Chairman Mao’s objections to repurposing a feudal relic, to spare the new nation the expense of building a headquarters.

Conservation units still in use in China typically fall into three categories. A handful are still operated by the unit to which they were originally assigned. The second type is found in restricted sections within a public monument or park, such as areas in the Summer Palace used as an on-site fire department and break rooms for the custodial staff. The occupant could also be unrelated to the park: Between 1959 and 2015, Jade Flower Island in Beihai Park was home to not only the White Stupa, but the renowned Fangshan Restaurant; at the Forbidden City, museum officials are trying to evict businesses like an antique dealer from inside the palace walls.

The third, most common type involve danwei that have long since upgraded to bigger, newer digs, usually outside the old city, but refuse to give up control of their old property. The danwei may, as in the case of Xiang Yuan, lease the property to other enterprises, or use it to house retired workers (who in turn often sublease to family, friends, or even tenants off the market). Landmarks of this third type are the bane of conservationists, as they no longer serve a “reasonable” purpose to the nation but have not been returned to the public. In addition, they have become an afterthought to the danwei, which no longer has much interest in seeing the property maintained or supervising tenants’ behavior.

In 2014, Beijing News reporters visited a complex formerly known as Tieshizi Hutong, home to a distinctive, gray-bricked Baroque mansion that was briefly China’s seat of government under the warlord Duan Qirui, Provisional Chief Executive of the Republic of China from 1924 to 1926 (the home’s other laurels include being the army and navy headquarters of the Qing empire, and site of the 1926 “March 18 Incident,” when anti-Japanese protesters were killed by Duan’s forces). This storied edifice and its three annex buildings, wood structures also built with European influence, were allocated to Renmin University in 1949 as offices and staff dormitories.

But following the relocation of the school’s Institute of Qing History to the new campus in northwestern Beijing, the main building has stood empty, and the current annex residents are loosely associated with the university at best. The complex was also, concluded Beijing News, in a state of “partial ruin”—the architectural details long eroded by tenants sealing the cloister-like exterior and cooking in the hallways.

Yet life inside these decomposing mansions goes on, a bizarre mix of squalor and faded splendor. Under the vaulted entrance of one of the annexes, an elderly resident surnamed Wang, who describes herself as the “mother-in-law of the daughter of former university employees,” is chopping vegetables on the aged stone steps when TWOC visits; a pair of shoes are dangling to dry from the colonnade. “It’s really quite terrible here,” she says conversationally, pointing out thin walls, a football-sized hole in the archway, and crown moldings worn smooth from neglect. These residents live under some of the highest ceilings and most intricate facades in the city—but also make do with communal toilets, makeshift kitchens, and sagging (if architecturally acclaimed) beams.

The former headquarters of China’s Beiyang government, currently empty but off-limits to all visitors not affiliated with Renmin University (Hatty Liu)

The residents, on their part, are unhappy with their reputation as relic-hating troglodytes. “We don’t want to live here anymore, either; nobody wants to see cultural relics destroyed,” an unnamed resident told the Beijing News. “I want to protect relics too, but can’t,” Wang’s neighbor Zhang tells TWOC cryptically. Wang translates: “Because it’s a conservation unit, we need permission from the heritage administration to do anything to the building…even to fix it; they have rules about how it should look and what materials to use.”

Kong, however, has told journalists that he had little real power to stop any danwei from making modifications to conservation units, and that the financial penalties are too small to deter them even from tearing down the building if they wished. The heritage administration’s hands, he said, are also tied by bureaucracy. “The tenants are danwei, a collective; if they say ‘we have no money for repairs,’ there’s no way to hold anyone accountable,” he told the Beijing News. It’s also hard to determine whom the property should revert to. “Old buildings may belong to the central government, to the city, to a district or county, or to an individual…[conservation] isn’t something a single department can handle.”

Instead, government bureaus and other organizations wishing to evict the danwei have typically had to resort to the same tactics as the Lees: compensation. This is the main reason why eviction targets are so hard to meet; according to Kong, the heritage administration’s annual conservation budget of 1 billion RMB is laughably small for paying danwei to give up their prime real estate in the city center—cash cows they’d been gifted for free. Negotiations between the Beijing Buddhist Association and Renmin University Press over the 500-year-old Nianhua Temple, which the latter had first used as a printing plant and then a commercial rental property, dragged on for 10 years after the press kept raising its demands from 30 to 50 million RMB.

Wang tells TWOC that there have been rumors that occupants will be evicted from Tieshizi Hutong, turning the main mansion into a museum, for at least 40 years, “but the longer they wait, the less they can afford it; I’m afraid it’ll never happen now.”

Contacted for comment, Norman Lee was adamant that private ownership is essential for guaranteeing the future of these relics, which has typically been the case for heritage property in the West. “Only then is there an incentive to take care of the property…my goal is to run [Xiang Yuan] as a private home with a private museum for my piano collection, but if that becomes too difficult, I will just maintain it as is and take care of that,” he said. This isn’t, however, a reachable goal for most properties in China, even if the original private owners could be found; the prospects of gathering documentation lost in the revolution, and simply running the years-long bureaucratic gauntlet, are daunting. “Most families choose not to claim their property,” he said.

But nobody quite knows who else has a claim either. As TWOC leaves Tieshizi Hutong, a security guard warily eyes a tour guide who is approaching the gates, lecturing a group of schoolchildren on the “March 18 Incident.” “I’ll allow it this one time,” he eventually says, and points to an imaginary line a few meters past the threshold. “Do not step past this point.”

ABANDONED ATTRACTIONS

It’s difficult to estimate the total number of occupied landmarks in China, as only the Beijing municipal government appears to have kept close tallies. The following examples from Chinese media remind us that people can feel at home just about anywhere.

(VCG)

The Secret Lab

In 2006, Sina reported from Jinan, Shandong province, that a grotty three-story building formerly belonging to Unit 1875, a Japanese biological warfare unit slightly less notorious than Unit 731, had been repurposed as workers’ dormitories and single-room apartments. A resident recalled sneaking into the basement to play as a child, “where we heard they used to do experiments on live people.” In 2007, the building became a city-level conservation unit but, as of 2015, Beijing’s Morningpost.com reported not much had changed besides a new plaque describing the building’s history.

(VCG)

The Longest Loan

One of the record-holders for the longest-occupied landmark in Beijing is the Taigaoxuan Temple, an imperial ancestral hall and part of the Forbidden City complex. According to Palace Museum officials, it was “borrowed” to hold an exhibition in 1950, and transferred to another organization afterwards. The museum finally got it back in 2013.

(VCG)

The Two Towers

An eyesore of southwest Beijing, the “twin towers” are a smokestack belonging to the Beijing No. 2 Thermal Power Plant, and the Tianning Temple Pagoda, first built in the 12th century. The pagoda was closed to religious and public visitors until 2007, after having gotten encircled by the plant’s campus. It was returned to the Beijing Buddhist Association after the thermal plant relocated, but locals haven’t seen the last of the smokestack—plans are afoot to turn the area into another industrial-themed art zone like the 798 District.

Occupational Hazards is a story from our issue, “Cloud Country.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.