An analysis of 19 translations of Wang Wei’s classic poems has just been translated—back into Chinese

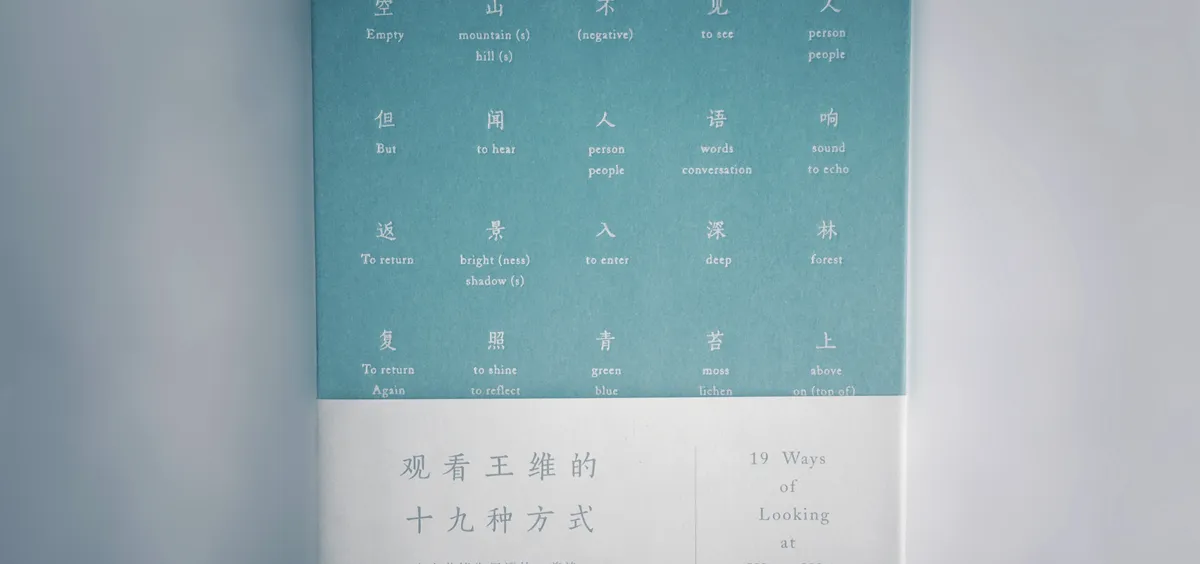

Poetry often demands to be translated, but rarely is the process easy or the outcome sufficient. Take “鹿柴” or “The Deer Park,” a 20-character poem written over 1,200 years ago:

鹿柴

王维

空山不见人,

但闻人语响。

返景入深林,

复照青苔上。

Its writer, Wang Wei, was famous for composing in the shanshui (mountains and water) genre. Fellow poet Su Shi once reflected that “There is painting in his poems, just like poetry can be read from his paintings.” With its simple setting of a lonely mountain, and images of forest, moss, and sunshine, “The Deer Park” is a classic genre piece from a writer often known as the “poetry Buddha.”

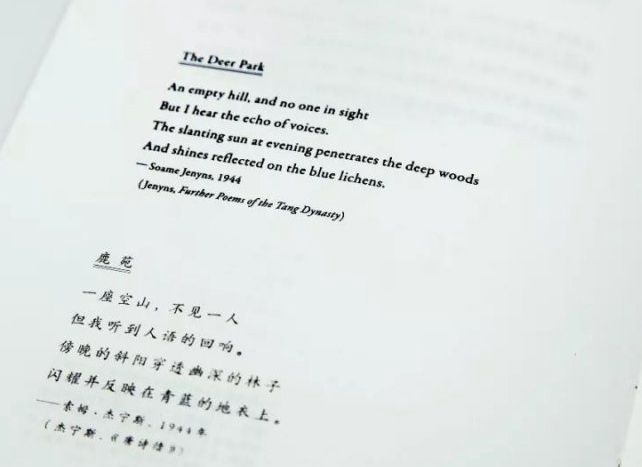

Most pre-school kids in China can recite this short, simple poem. In translation, however, things become more complicated. “The Deer Park” has been widely translated into several different languages, including English, Spanish and French, each with their own challenges and limitations.

Even the title “鹿柴” is open to interpretation—is it any park, a particular park, or even an abstract reference to the park in Sarnath, where Gautama Buddha first taught the Dharma? In translation, it’s impossible to convey all these meanings. Or take the second sentence (“the only voice can be heard (但闻人语响),” which, since nouns aren’t given singular or plural forms in Chinese, could refer to either a conversation or private monologue.

For American translator and writer Eliot Weinberger, this is all part of the charm of the job. Weinberger has collected different versions of “The Deer Park” from all over the world, and in his book 19 Ways of Looking at Wang Wei, chose a select number to introduce and review, from simple transliterations to Kenneth Rexroth’s highly loose interpretation. As Octavio Paz writes in an afterword to the book: “Eliot Weinberger’s commentary on the successive translations of Wang Wei’s little poem illustrates, with succinct clarity, not only the evolution of the art of translation in the modern period but, at the same time, the changes in poetic sensibility.”

Now, Weinberger’s book has been translated back into Chinese, and published by the Commercial Press. Whether you are interested in Chinese poetry, or simply curious about the vagaries of translation, it comes highly recommended.