Chinese social media has a habit of making homeless individuals “famous”—with unintended consequences

A Shanghai scavenger with a propensity for spouting verse has become a viral sensation among the live-streaming community, much to his dismay—and he’s far from the first homeless man in China to regret finding online fame.

Shen Wei, 52, an ex-employee at Shanghai’s Xuhui District Audit Bureau who has been on sick leave since 1993, is known online as the “Wandering Poet” for his feats of literary learning. Since he was evicted from his apartment in 2002, Shen has lived around the Yanggao South Road subway station where he recycles garbage, feeds stray cats, and collects books—but it’s the latter interest that led dozens of Douyin (aka TikTok) and Kuai Shou (Kwai) enthusiasts to film themselves with Shen quoting lines from gaoxue classics such as the Analects of Confucius, The Commentary of Zuo, and The Book of Songs.

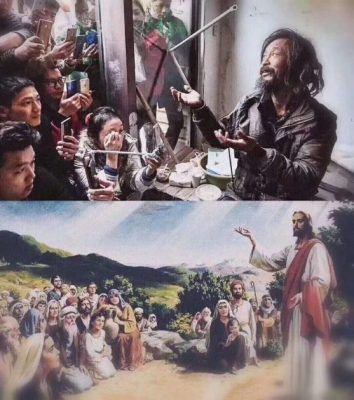

Once Shen’s fame spread to Weibo, posts about him generated millions of views, including a marriage proposal. Crowds have flocked to Yanggao Station to snap selfies, hold up scribbles of his wisdom (“we are all frogs at the bottom of the well, and must continue to learn”) on bits of cardboard, and try their best to turn the unwilling street poet into a meme.

Memes comparing Shen to Jesus appeared on Weibo

One user from Sichuan summed up the appeal: “At first glance, I pitied him. When he started speaking about the knowledge in the books, I pitied myself.” But as clips began to spread of these smartly dressed wanghong, jostling each other to post their own videos with Shen—one woman reportedly arrived in a BMW with an eight-person entourage—commentators expressed disgust at the sight of live-streamers “buzzing like flies” around an impoverished person, seemingly more interested in the short-term boost to their own personal “brands” than Shen’s privacy and wellbeing.

“Everything I’ve done has always been about reading,” Shen told The Paper—and it was this habit of collecting trash and books that apparently prompted his suspension from work in the first place. Shen was twice sent to a psychiatric hospital, and has refused his family’s help (his three siblings have apparently given up on him). Meanwhile, his fame has drawn attention from former colleague at the audit bureau, who are investigating why Shen continues to receive 2,000 RMB a month in sick pay, and severely tested his patience: “I can’t really handle this. I just want peace and quiet,” Shen said, explaining that “out of politeness, I won’t turn away anyone” but would rather people simply “read more books.”

The whole incident recalls the saga of 34-year-old vagrant Cheng Guorong, also known as “Brother Sharp” (犀利哥), who attracted admirers online back in 2010, after photos showcasing his prominent cheekbones and “boho” dress sense were shared as prime examples of supposed “homeless chic.”

Cheng became an overnight celebrity for his looks (ifeng)

Cheng had been a migrant worker who retreated onto the streets of Ningbo after a robbery left him too poor to send money home, and too ashamed to ask for help. After the amateur snaps made him famous, netizens donated money and the media descended on his family home in Nanchang, where relatives said he had been left withdrawn and traumatized from years of living rough. Observers complained that Cheng’s mental health was being severely tested, too, by the overzealous attention of so many netizens. Although Chen’s story predates the age of Douyin, he, too was bombarded by offers to monetize his fame: fashion retailers considered making Brother Sharp their brand ambassador, there was talk of trademarking his look, and a film director was pitched an inspiring biopic about his travails.

But four years later, following a stint of treatment at a psychiatric institution, Cheng was believed to be back on the streets of Jiangxi. Perhaps that was what he wanted, his brother suggested, pleading with reporters to leave Cheng alone. (Last year, photos of another homeless man, believed to be a former soldier, drew comparisons with Brother Sharp for his “regal” posture, and highlighted the trend of social media churning out “wanghong vagrants”)

The unnamed man was admired for a picture that suggested he carried himself “like an emperor” (ifeng)

In 2012, a laid-off factory worker-turned-transgender garbage collector Liu Peilin, shot to fame after appearing in a local news report about a small fire in a Qingdao alley. With his exaggerated makeup and preference for women’s clothing, Liu had suffered endless discrimination while living on the margins of society, and well-meaning netizens soon descended on Qingdao, dubbing him Brother Joy (大喜哥), and whipping up the now-familiar media storm.

While his celebrity helped bring in job offers, Liu was forced to abandon the women’s clothing he’d worn for 16 years and put on menswear in order to accept them. As of 2018, though, he had seemingly given up trying to get society to accept him, and was back to his subsistence lifestyle—another throwaway victim of netizens’ bottomless appetite for spotlighting homeless men for their curiosity value, with little consideration of how the noxious effects of fame on those living on the bottom rungs of Chinese society.

Cover image from VCG