The Chinese roots of the global social media craze

When Tik Tok hit the Appstore earlier this year, it quickly became one of the top free apps from the US to Japan to Thailand, with over 1 billion videos watched each day. The new social media platform allows teenage Tik Tok fans lip sync to their favorite songs, do silly dances, and make funny videos.

The tale of Tik Tok is that of a meteoric rise, taking place in Shanghai, Beijing, and Silicon Valley; born out of a synergy between music video app, musical.ly, and Beijing startup, Bytedance.

Although musical.ly looked quintessentially western when it was first released in 2014, it actually was a Chinese creation. It was founded by Zhejiang University graduate Alex Zhu, who was looking for the next billion-dollar technology craze (perhaps inspired by his first boss, Jack Ma—Zhu’s LinkedIn profile states he spent nearly two years working at Ma’s first company, Chinapages.)

In 2013, Zhu and a friend, Louis Yang, raised a reported 250,000 USD from venture capitalists and spent the six months developing an app for playing five-minute educational videos. But, “It was doomed to be a failure,” Zhu told Business Insider. In 2014, with only about 8 percent of their original investment left, the team decided to pivot their business strategy completely. Within 30 days, musical.ly was launched.

Alex Zhu shares how his entrepreneurial failure positioned him for success (Youtube)

Zhu says he had been inspired by a group of American teenagers on a train; half of whom were taking selfies with silly filters, while the other half listened to music: Why couldn’t the two be combined into one? Musical.ly began with the idea of a simple interface that allows users to record, edit, and share videos of themselves dancing or lip-syncing to pop music hits, with special effects and filters provided. Moreover, Zhu realized that with the cutthroat competition in the tech sector, it was necessary to reach out to technology’s the earliest adopters: “Teens have an entrepreneurial spirit that allows them to try new things and, most importantly, they cross-promote,” he told Adweek.

His growth strategy proved successful: an estimated 60 percent of musical.ly’s 100 million users across North America, Europe, and Latin America were under the age of 20. As the app grew in popularity, celebrities and brands began knocking on the door. Katy Perry released her song “Chained to the Rhythm” on the app, which other users set as the background music to their own videos. For many industry insiders, the app’s success was surprising, as musical.ly was perhaps the first social media app innovated in China that was successful in the US. (Except for a handful of business development and marketing employees based in a coworking space in California, the rest of musical.ly’s employees were located in Shanghai.)

Coca-Cola even launched “Share a Coke” campaign on musical.ly, utilizing the app’s unique user-generated ad campaigns (Shorty Awards)

Zhu’s dream to come up with a billion-dollar-idea proved prophetic: Within three years of creating musical.ly, the app was bought at a reported $1 billion price tag by the Chinese startup, Bytedance.

Bytedance itself was no stranger to the 15-second music video market. Indeed, while musical.ly was slowly gaining market share in the West, a similar app was exploding in China, underneath the Bytedance umbrella. In 2016, thirty-something Robert Liang launched a short music video app called A.Me, renamed “Douyin” (“vibrato” in Chinese) a few months later.

In a country whose technology sector is overwhelmingly controlled by the so-called BATs (an acronym for Baidu, Alibaba, and Tencent), an independent success story like Bytedance is a rarity. Headed by self-made entrepreneur Zhang Yiming (who was ranked #7 in Fortune Magazine’s “40 Under 40”), Bytedance has made waves in China through its Jinri Toutiao news-aggregation app (which is driven by artificial intelligence), the ubiquitous Douyin, and its recent takeovers of numerous overseas companies, such as Flipagram.

Additionally, Zhang has raised the company’s public image by allegedly rejecting a massive Alibaba investment in order to maintain the company’s independence, and having a very public spat with Tencent head Pony Ma, accusing the internet giant of plagiarizing Douyin. (Ironically, until recently, Douyin also faced criticisms from users of “copycatting” musical.ly, essentially providing a Chinese-language version of the latter.)

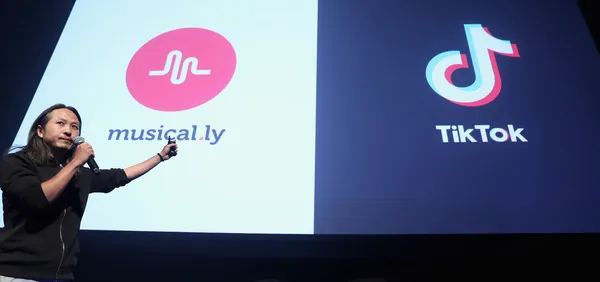

After the Bytedance buyout of musical.ly in November 2017, Douyin was poised for international expansion. The musical.ly app was rebranded as “Tik Tok” and took on Douyin’s user interface. There are 500 million active monthly users, 150 million of whom watch videos every day.

However, while Tik Tok connecting teens across the world through music, China is visibly removed from the action. On the mainland, users do not access Tik Tok’s global network, but rather continues to watch and upload on the original Douyin platform (perhaps due to Bytedance’s recent censorship run-ins with the government.)

After nearly a decade of accusations of copying western social media (such as with websites like Youtube-copycat Tudou and Facebook-copycat Renren), the success of musical.ly and Douyin, both inherently Chinese creations, suggest that Chinese social media innovations have international appeal–and Chinese tech entrepreneurs are here to stay.

Cover image from Zimbio