How a tabby cat mini-game helped transform China’s e-commerce ecosystem...not always for the better

The machine that has subjugated me and taken control of my mind and body is no violent robot, no misanthropic computer system from the far future; no Matrix, no SkyNet—but a grinning character named SkyCat. From her feline fruit farm she commands millions of minions like myself. “Collect my Meow Fruit,” I hear its voice in my head, “the more you serve me, the more you shall have yourself.” I can’t resist.

SkyCat (tianmao in Chinese) is a mini-game inside the Alibaba-owned e-commerce platform Taobao, but it’s much more than that. I’m barely awake in the morning and it is the first thing on my mind. I pick up the phone and open the app, seeing endless ads for products the algorithmic ad engine selects for me. I navigate to my dashboard, the place where I can track the status of my orders. I come here dozens of times a day, sometimes staring at the dashboard for minutes on end, waiting for orders to change status from “shipped” to “being delivered.” My heart rate increases: a small rush of dopamine.

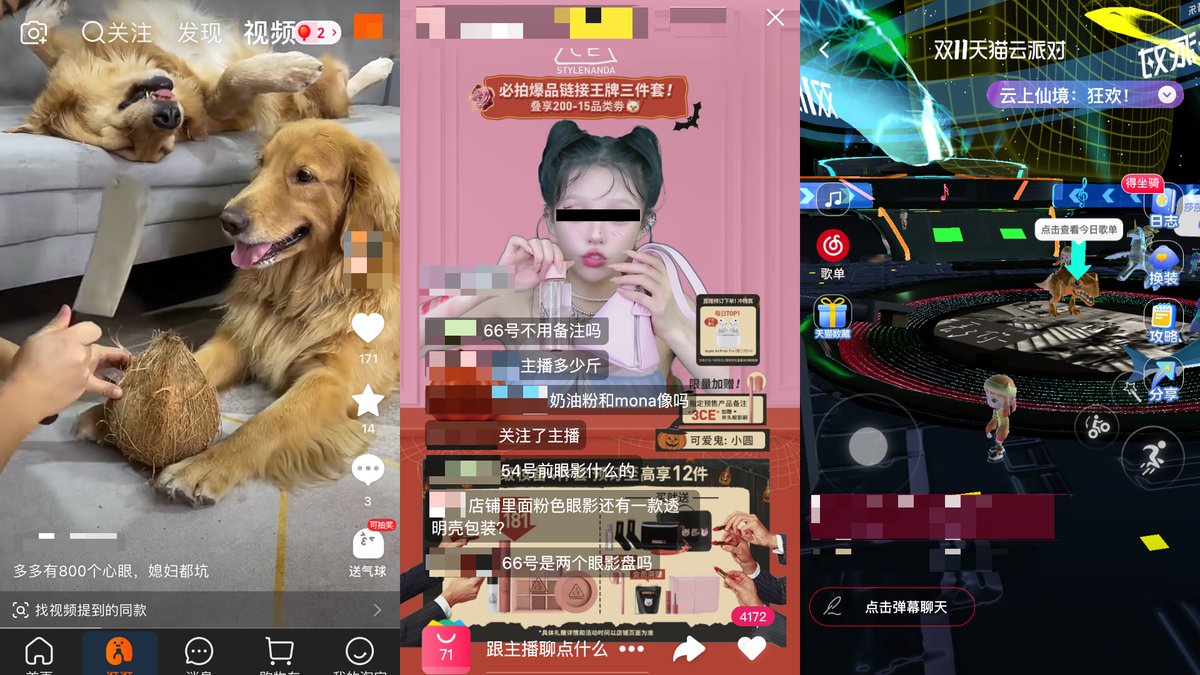

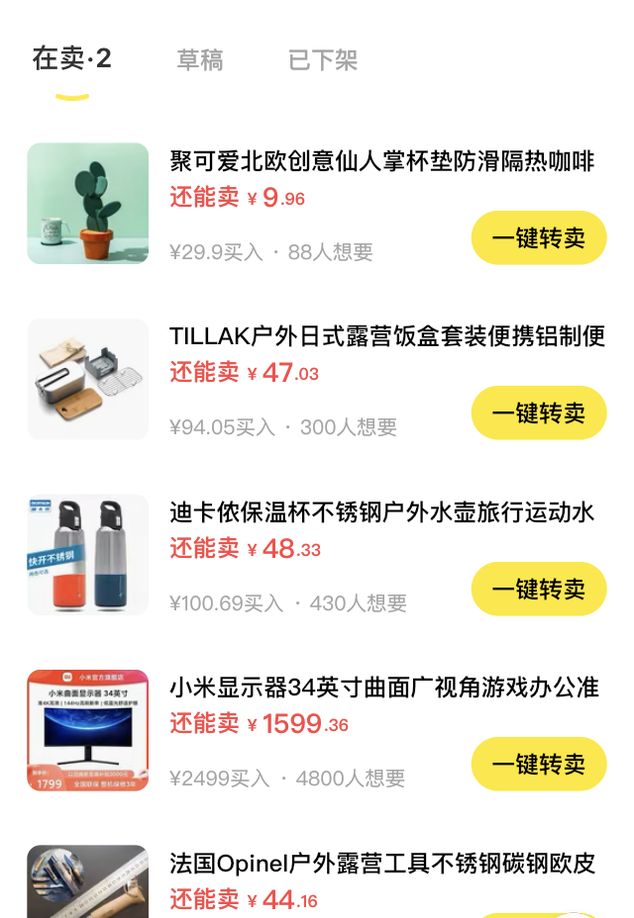

SkyCat is just one of the ways Taobao, China’s largest online shopping platform, keeps consumers hooked. Taobao is sometimes compared to its online shopping competitors from the West, but Alibaba’s monstrous creation is a step ahead: Taobao integrates online shopping with social media features and entertainment, making it one of the 10 most downloaded iPhone apps in China, even ahead of TikTok, WeChat, and Baidu, with well over 800 million monthly active users according to data from SensorTower and Statista. The app works in unison with Xianyu—another app owned by Alibaba to re-sell used items, the money from which is transferred directly to Alibaba’s payment app Alipay, which can be used to pay for new things on Taobao: such is the endless cycle of consumerist hell.

In the days leading up to November 11, or “Singles’ Day,” Chinese consumers will spend billions on the platform—the figure was 869 billion yuan in 2020. To reach those numbers, Taobao employs a range of techniques, from gamification to inferential analysis via its powerful algorithms, to keep regular shoppers like me spending.

Play games, win dopamine

In SkyCat, the orange tabby cat on my screen is equipped with a giant vacuum sucking up endless fruit in exchange for minor coupons and other deals. Mini-games like this are everywhere on Taobao: Shake your phone to win bags of coins; watch livestreams to collect pearls; spend virtual currency to buy clothes for your virtual avatar to take selfies with. You can spend hours inside the app.

This process of adding game elements into traditionally non-game environments like a shopping platform is called gamification. “Gamification has a relatively long history in China, since the early 2000s,” Hong Kong game designer and researcher Allison Yang tells TWOC. These gamified elements are added for a reason. “A lot of consumption and even labor, when gamified, can pretend it is not what it actually is,” Yang explains. “This helps the users forget that they are consuming, instead believing they are playing.”

The game mechanics may even tap directly into our minds, activating our rewards system, the structures of the brain that regulate rewarding and pleasurable experiences. “A lot of gamification production heavily borrows this mechanism, level designers and balance designers make great efforts calculating users’ psychology to create the utmost pleasure,” says Yang.

It has long been known and acknowledged that these rewards systems based on the neurotransmitter dopamine are involved in substance abuse and addiction. The body can become reliant on a substance to maintain releases of dopamine and the rewarding and pleasurable feelings that come as a result. A 2021 study in the Journal of Behavioral Addiction finds a vast majority of surveyed experts agreeing that compulsive shopping “should be recognized as a distinct psychiatric diagnosis, best classified as a disorder due to addictive behaviors.”

Taobao wants users to spend as much time and money on its platform as possible. Games like SkyCat are one way to achieve that, but not the only technique.

Your preferences, inferred and optimized

“How do I tell real from fake? (asking for a friend),” I type into a livestream chat box where the seller is flogging Louis Vuitton bags. I’m not interested in the products, but I’m mesmerized by the host. She stops her presentation and looks directly at me with a smile. For a brief moment, I feel a little less lonely. “You see this blue tag? All our bags have this tag, this is how you can verify authenticity,” she tells me, going into great detail about how to avoid fake products. “Make sure to subscribe to our channel and please like this livestream!”

A moment passes and she gets upset: “How come you still haven’t subscribed and left a like, we answered your question in such great detail!” She is right, I should give something back. I feel the urge to comply and tap on the heart a couple of times, leaving a few “likes.” She then continues her presentation. I don’t know anything about luxury bags, but the one on offer seems like a steal compared to the original retail price, and there is only one left.

Just as a livestreamer subtly manipulates viewers, Taobao plays on consumers’ biases to keep them spending. We like to believe that we are rational beings, but we are continually under the influence of cognitive biases—patterns of perception and cognition prone to errors, mental shortcuts so to speak, as a result of how our brains evolved to process information.

Platforms like Amazon or Taobao “have a business interest in maximizing their profits,” Berlin-based user experience designer Victoria Kure-Wu tells TWOC. “Ideally a user on the platform is converted into a shopper, this is called conversion rate,” she explains. “Users are not directly manipulated, but cognitive bias is utilized to increase conversion rate.”

One such cognitive bias is the anchoring effect, whereby our perception of one thing is influenced by a previous point of reference, for example when a crossed out higher retail price is followed by the lower current price. The higher price serves as a reference point, making the lower price seem like an even better deal, as with the Louis Vuitton handbag in the livestream. Then there is the phenomenon called reciprocity: We tend to feel the urge to return favors. A free sample, for example, or a gift with an order can be perceived as such a favor, increasing the likelihood of a customer spending more money to return the favor.

Another widely employed technique revolves around scarcity. “Humans tend to prefer a product when its quantity is limited,” Kure-Wu explains. If a product seems scarce—perhaps due to a pleasant livestreamer telling us there is only one left in stock—we are more likely to buy it. All this is to increase the likelihood of converting users into money-spending, algorithm-feeding shoppers.

Once fed, the algorithm is powerful enough to infer what shoppers desire, before even they know what they want. My own algorithmic downward spiral began with large-breasted women. Sometime a few months ago the endless stream of ads and product suggestions filled up with conspicuously large-breasted models, although I had never bought nor searched for women’s apparel. It grew more sinister when ads for girls’ underwear—and girls’ underwear only—started popping up. I don’t have any children.

The scantily clad women and young girls were punctuated by ads for weight-loss pills and lotion to treat a certain skin condition. I had never searched for anything like that, yet the ads were eerily relevant to me. Here they were, the most traumatizing chapters of my family history, my deepest insecurities, staring right at me.

This endless advertising engine is powered by what Professor Sandra Wachter from the Oxford Internet Institute describes as “inferential analysis.” A user profile and ad suggestions are generated not simply based on hard data provided by users—things like age, sex, address—but based on the inferences that can be made by analyzing behavior on the app. For example, the app could infer that I am male even if I hadn’t explicitly told it so because I have been buying, say, lots of shaving cream and razors.

A lot can be inferred based on user behavior, including very sensitive things like sexual orientation, or even mental health. Everything users do on the app feeds the algorithm with data to gauge their interests, categorize them, and put them into what Wachter calls “affinity groups” based on similar attributes to provide ever more relevant ads and keep users on the app.

This inferential analysis can amount to massive breaches of privacy but it gets worse when inferences drawn are used against us: “I may not be shown certain job listings or I may be targeted with higher-priced ads for example. But we don’t know that we’re being evaluated and filtered. This is done behind our backs. And the law currently falls short of addressing these issues,” Wachter tells TWOC. Article 24 of China’s Personal Data Protection Law, enacted in November 2021, vaguely stipulates that “automated decision-making shall ensure the transparency of the decision-making and that the results are fair and equitable,” prohibiting “unreasonable differential treatment of individuals in transaction conditions such as price.”

What this means in practice is murky, and details about Taobao’s automated decision-making systems are scant: “Based on the personal data provided by you and your behavior while using our services, we predict your affinity groups and preference characteristics and manage your system accordingly” it states in the app settings under ads management.

I reach out to Taobao customer service to find out what exactly that entails. I have opted in, I have agreed to having my behavior on the app analyzed, the customer representative reminds me on the phone. This increases the accuracy of the ads shown and improves my experience on the app, he explains. An experience I find more and more unsettling. The ad engine is so dynamic, it almost seems like a living system, a machine that exhibits behavior (worthy of scientific inquiry much like animal behavior, as some researchers are suggesting), behavior constantly changing based on the input and feedback I provide. The only way to delete my data, is to delete my account, the customer representative says cheerily.

Fighting the machine

In the mid-20th century, when mathematicians and engineers like Norbert Wiener and Qian Xuesen first developed and applied cybernetics—the study of control in animals and machines—they were working on things like guided missiles for the military. A controller receives information from the missile, velocity and pitch for example, and based on that information sends commands to the servomechanism to adjust course, which in turn sends updated information as new input data in an endless feedback loop until the missile reaches its target.

It seems that I had become the projectile, controlled by Taobao’s behavior-steering algorithms, stuck in the never-ending feedback loop of e-commerce. I am the meatbag missile headed for my own destruction, financially, socially, mentally.

On Taobao with only the orange tabby cat on my screen for company, I struggle to suck up meow-fruit as it grows back faster than I can collect it. Sometimes a treasure chest appears out of nowhere, opening it takes me to some brand’s livestream which I have to watch for at least one minute to get 10,000 extra meow-fruit. I’m taken back to the farm and for a limited time, the vacuum is upgraded to a super-vacuum, sucking up even more of the feline fruit. It never stops.

But liberation from the shackles of SkyCat and the e-commerce ecosystem it inhabits has been close at hand all along, I discover. In fact, it has been attached to my body all this time. It is my middle finger. I extend it and theatrically point it at the screen of my phone for a few seconds, then use it to long-press the app symbol: Delete.

But I have done this many times already, only to re-install and start using the app again shortly after. Especially recently, with Singles’ Day upon us, the purrs of SkyCat are more enticing than ever.

Screenshots and pixellation by Roman Kierst