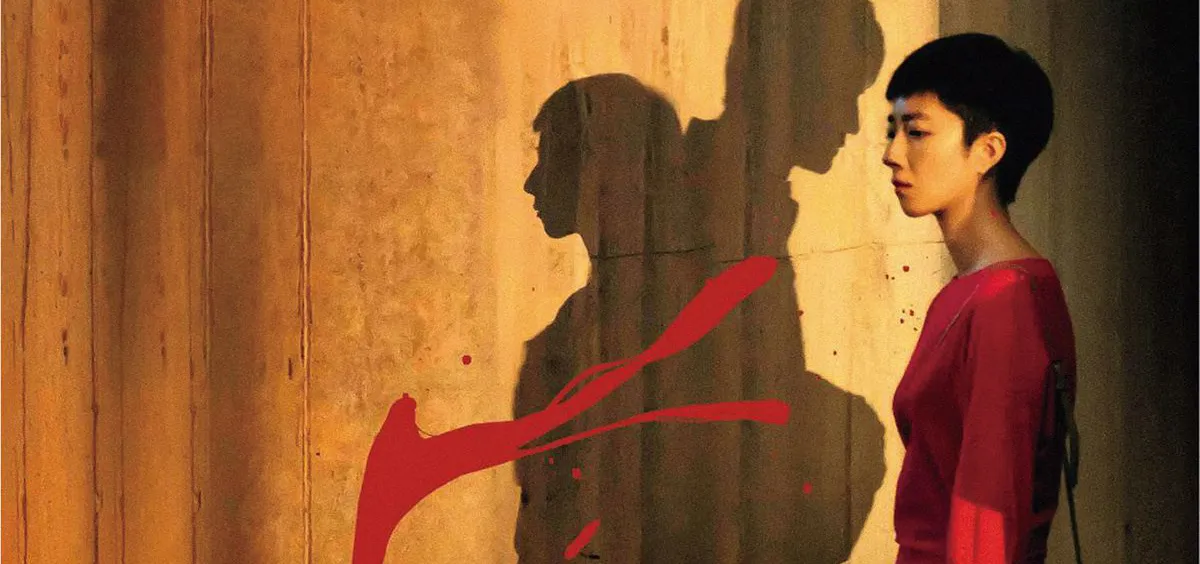

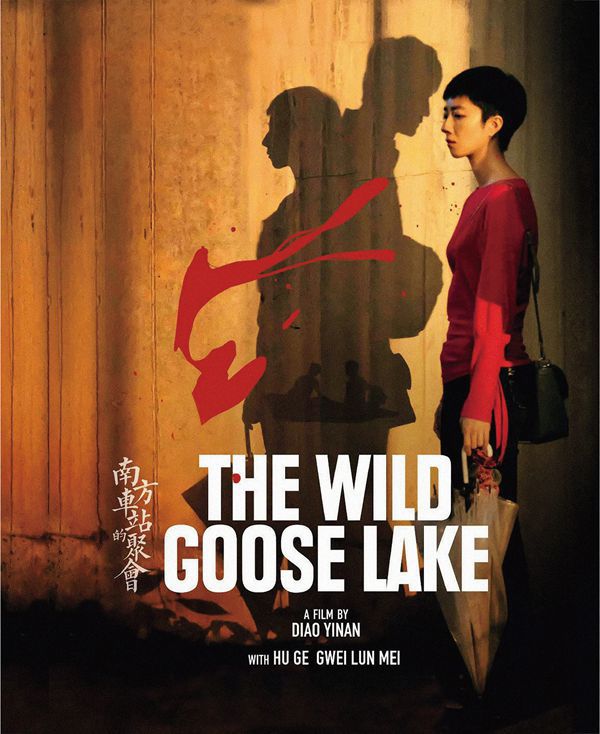

Diao Yinan’s stylized film noir tackles violence, crime, and the marginalized

A woman in red borrows a lighter from a disappointed man on a rainy night in the underpass of a small train station, and they strike up a dubious conversation in the Wuhan dialect: Why didn’t the man’s wife show up? Could the woman take her place?

Thus begins The Wild Goose Lake, whose Chinese title translates into Rendezvous at a Southern Train Station. The only Chinese film to compete at the 2019 Cannes Film Festival, it attracted the notice of Quentin Tarantino on its opening night in May.

Director Diao Yinan previously won a Gold Bear for Best Film at the 2014 Berlin International Film Festival for Black Coal, Thin Ice. This and Wild Goose’s subsequent international fame may have paved the way for the latter’s public release in mainland theaters in December, a rare case within its genre.

Scenes of shootouts, decapitation, and rape are usually off-limits in a country that lacks a content rating system, yet Wild Goose offers such depictions in spades. In one of its most gruesome scenes, rival gangsters skewer each other with umbrellas; the thrill of the conflict is amplified by watching an everyday object suddenly turn violent.

The film noir unfolds with flashbacks of fugitive Zhou Zenong (Hu Ge), the ringleader of a low-level gang of a motorcycle thieves in Wuhan, and the night it all went wrong: A turf war had escalated into bloodshed and horrific murder, and a panicked Zhou shot and killed a policeman.

Wounded and in hiding, Zhou learns that there is now a reward of 300,000 RMB for his capture, which he hopes his estranged wife Yang Shujun (Wan Qian) can collect. Liu Ai’ai (Gwei Lunmei), an escort working at a lakeside resort, agrees to pass messages between the couple, but this beautiful informant’s true loyalty and motive are unknown.

The setting, a fictioned Wuhan “urban village” named Wild Goose Lake, is a murky place unsettled by poverty and migrant workers, where crime runs rampant—an underbelly of Chinese society rarely seen on the big screen. Dark alleyways, dingy diners, and shabby apartment complexes serve as the backdrop of many night scenes. Over 2,000 amateur actors appeared in the movie, most hired locally. For one chase scene that culminates in a shootout in an apartment block, the entire building’s residents were hired to play themselves.

Many of the film’s plotlines were inspired by real crimes. The central story is based on a 2014 case, where a fugitive in northeastern China showed up at his niece’s house in order for her to collect the 100,000 RMB bounty on him. A scene where motorcycle thieves gather in a hotel basement to exchange tips and hold a stealing competition was also ripped from a 2012 Wuhan headline.

Hu Ge, well-known for acting in historical and fantasy TV series, plays against type in the role of a desperado

In the film, as in real life, there is no clear distinction between the good guys and the bad. In chase scenes, the audience can hardly tell the police from the gang, while scenes of the officers dividing up jurisdictions for investigation recall amusing parallels with criminals dividing up territories for theft.

In another sequence, where the police search for Zhou in a zoo at night, the artful cinematography mirrors the hunter-prey dynamic of the jungle. An aesthetic moment sees the wounded and hallucinating Zhou point his gun at a wall covered in newspapers, as the pictures come to life and make sounds.

Wild Goose creates a highly stylized movie universe with saturated shades of orange and magenta, excellent sound design that often elevates scenes emotionally, and sophisticated camera work. In one chase scene, the shot focuses entirely on the shadow cast by the fugitive. As he runs away toward the light, his shadow stays fixed on the wall, becoming larger but also translucent.

The film shows a clear weakness when it comes to storytelling, spending most of its time on world-building rather than constructing the narrative and furthering character development. Neither the fugitive Zhou nor the escort Liu has any backstory. How did they get into their present situation? What issues from the past are they motivated by?

The lack of character complexity has led to some confusion among Wild Goose’s audience, such as when reviewer Laoyueyeliao concluded in a WeChat article that the film was trying to exonerate Zhou’s crimes as attempts to take care of his family. Such a vastly deviant interpretation shows that the film could still do a better job displaying the complex existential struggles of Zhou and Liu, and others who live on the edge.

Liu Ai’ai: Are you really Zhou Zenong?

Dàgē, nǐ shì Zhōu Zénóng, Nóng gē ma?

大哥,你是周泽农,农哥吗?

Zhou Zenong: What?

Shénme?

什么?

L: Your wife can’t make it.

Nǐ lǎopo lái bù liǎo le.

你老婆来不了了。

L: If you’re willing, I can take her place. If you’re not willing, I’ll leave right away.

Nǐ yàoshi yuànyì, wǒ kěyǐ tì tā. Nǐ yàoshi bú yuànyì, wǒ xiànzài jiù zǒu.

你要是愿意,我可以替她。你要是不愿意,我现在就走。

L: Brother, you’re lucky. Haven’t you thought about running away?

Dàgē, nǐ yùnqì mánhǎo, méi xiǎngguo pǎo ma?

大哥,你运气蛮好,没想过跑吗?

Z: Where to?

Wǎng nǎli pǎo?

往哪里跑?

L: To the south, all the way to the south.

Wǎng nán a, yìzhí wǎng nán.

往南啊,一直往南。

***

Four More Must-See Movies

Changing China

Subtitled “Life is Marvelous Because of You,” which is also the title of its theme song by the pop-punk band New Pants, this “inspirational” documentary follows six individuals of varied professions—a deliveryman/boxer, a doctor, a teacher, a policeman, a researcher, and the CEO of China’s first private commercial rocket company—as they strive to pursue their dreams, big and small. While a 106-minute film cannot begin to represent all of China’s multi-faceted modern society, it’s a worthy attempt to record the present-day lives of ordinary people.

Summer Detective

Two seniors in a Hebei village, Chaoying (Xu Chaoying) and Zhanyi (Zhang Zhanyi), inquire into a hit-and-run that landed their friend in a coma with a huge hospital bill. Unexpected funny moments abound, as the two turn to a shaman, a web of rural guanxi, and their own ingenuity to investigate and confront the suspects. The depiction of the tranquil, beautiful countryside is dotted with wacky scenes like a cow being lifted into the air and goldfish swimming in plastic tarp on the ceiling. This magical realistic tone is completed by the true-to-life performances of the all-amateur cast, yet the film never loses the dark humor at its core.

Gone with the Light

A mysterious white light shines over a city, and afterward, certain people have disappeared. Many of them vanished in pairs, leading to rumors that only those who have found true love were taken. High school teacher Wu Wenxue (Huang Bo) and his wife Zhang Yan (Tan Zhuo) are both left behind, and start to ask awkward questions about their 18-year marriage. Career woman Li Nan (Wang Luodan) meets her husband’s mistress, and uncovers many other secrets. Street gangster Kuaizi (Bai Ke), obsessing over an old friend’s disappearance and suspected murder, is forced to confront his sexuality. All have to find their own answers to the question: Is there an ultimate arbiter for love?

Only Cloud Knows

Director Feng Xiaogang’s (1942, I am Not Madame Bovary) latest production is a departure from his past works in historical drama and urban comedy, spanning several decades in the love story of Sui Dongfeng (Huang Xuan) and Luo Yun (Yang Caiyu). The two protagonists meet in their 20s in New Zealand, but despite their obvious attraction, Luo seems to be holding back. Eventually, the two get married and begin running a Chinese restaurant together, happily for the most part, in spite of Luo’s constant struggle for a sense of security. She has been hiding a secret that can only be pieced together after her death. The film is based on the real-life experiences of a friend of the director’s.

The Wild Goose Lake is a story from our issue, “Alpine Ambitions.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.