Playwright and composer Jason Ma honors Chinese heritage in American theater

When Jason Ma was crowned math champion of his school in southern California at age 13, he quips that his immigrant father “must have been very pleased.” Yet he claims his math prowess never quite recovered after his parents took him to see his first musical, A Chorus Line, during which “all the electrical activity in my left brain must have rushed over to the right hemisphere” and “thus, a theater artist was born.”

In 2017, the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers (ASCAP) honored Ma with its Cole Porter Award in recognition of his decades-long career on dozens of Broadway and Off-Broadway shows. The Chinese-American actor, playwright, and composer’s skills were on full display in his most recent musical Gold Mountain, in which 19th century Chinese railroad workers in the American West chorus: “The blisters rise/ We build the tracks/ And it breaks our backs…/ We curse the heat/ And we try to eat…/ A Chinaman dreams of something.”

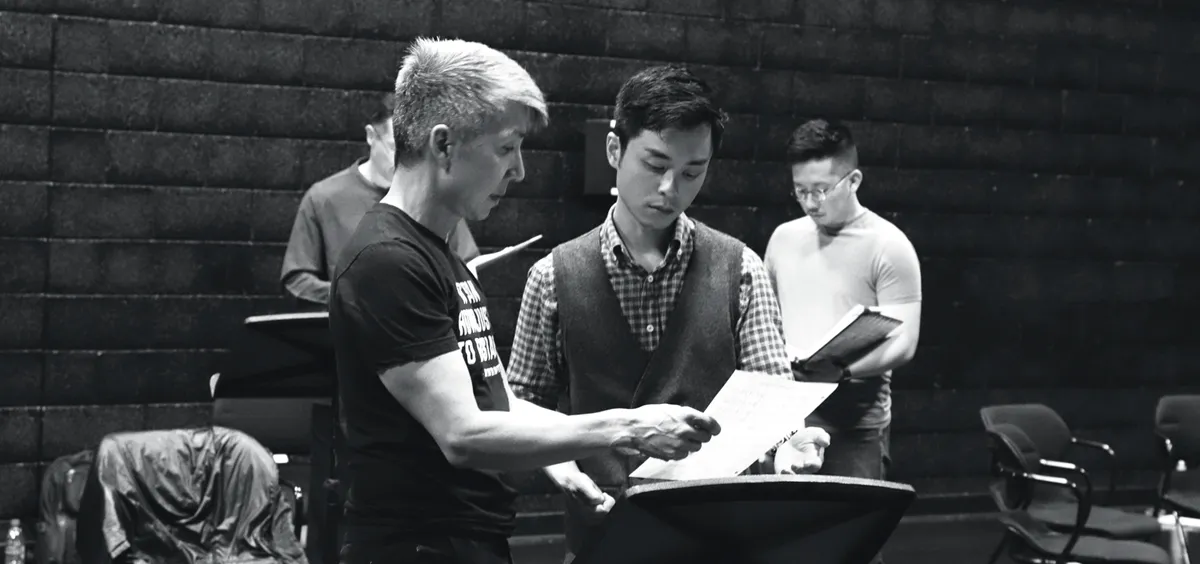

Sung as part of the 150th anniversary celebration of the completion of the transcontinental railroad in the US in 2019, Ma’s lyrics of love, longing, resistance, and survival dramatized the build-up to the Great Strike of 1867, in which thousands of Chinese workers put down their tools and demanded better wages for their oft-overlooked blood offering to American history. First staged at the ASCAP/DreamWorks musical theater workshop in 2016, versions of the musical have since graced audiences in San Francisco, Los Angeles, New York, and Salt Lake City, as well as the former railroad town of Ogden, Utah, featuring a mostly Asian-American cast and starring Ali Ewoldt of The Phantom of the Opera.

Yet Ma confesses that Gold Mountain was actually written in 1994, but was rejected by producers for decades and sat in a box under his bed until 2015, when people were ready to really “hear it.” Speaking over the phone with TWOC, Ma discusses Broadway’s evolving attitudes toward Chinese American voices, the forgotten stories that Gold Mountain resurrects, and the enduring emotive power of musical theater.

How did you begin writing and composing the musical?

I was performing in the show Miss Saigon on Broadway, and I became a bit restless creatively. I was waiting to go on stage, and a little tiny song fragment started to come to me. It was the part [of Gold Mountain] where the two young lovers are on a hillside in the Sierra Nevada, and they are sharing what they miss about China. The man says, the mountains here are beautiful, but they don’t look like the mountains back home.

Over the next few weeks, for the rest of the summer, all my time off, and even backstage when I had some time, I was just writing and writing, obsessed with it. I had a complete draft by the middle of fall. That song fragment turned into a duet between the two lovers, and that was the first full song. You know, the young woman’s name is Yu Mei. That’s my mom’s name. And my father’s name [which is the same as the protagonist’s] is actually Lit Ning, and it’s an interesting homonym for a lit fuse. It’s a special piece to me; my family and friends are embedded all over the place.

Gold Mountain is a love story against the backdrop of Chinese immigrant labor and resilience

Why did it take two decades to get the show on stage?

What’s been interesting about this particular piece for me is that [producers’] initial reactions to this story—the idea of this piece, and the idea of me as a writer of musical theater—was actually very weird, hostile, and racist. I got comments like, “It doesn’t sound like you wrote this”; “this sounds so much like a Broadway musical”; “it sounds like two white Jewish guys wrote this”; “why don’t you try to make Chinese opera more accessible to other audiences?”

Back then, there was no filter on this kind of stuff. I didn’t have the vocabulary to describe what was going on; I just knew it was negative, and not welcome. I put the piece away after a lot of similar rejections. But every decade, I pulled it out of its box for one reason or another. Each time, I got to see the reaction to it evolve. People began to hear it. The criticisms that it didn’t sound like me, didn’t sound Chinese enough, sounded too Broadway, started to go away.

Over the decades, people became more educated, or more aware. YouTube probably helped. The world started getting smaller; we started to see clips and music and movies from other countries. Particularly with China, there’s been much more of a back and forth culturally since the 90s. And then there are pioneers, like [the creator of Hamilton] Lin-Manuel Miranda, and people start to see that musicals don’t have to be only written by straight white men; they can be written by anybody.

So I think that’s why all of a sudden in 2015, this fairly old piece of mine gained traction. When we were accepted into the ASCAP workshop, as the men were walking on stage, the audience started to spontaneously clap. And I think that’s because they’d never seen an opening number where all of a sudden the stage filled up with Asian men. What musical starts with that? So that was very exciting to them, and after the opening number, the ovation was quite amazing.

Ma (center) was a speaker at the Museum of Chinese in America’s 2019 Lunar Soirée

Why did you choose to run the show in Utah last year, over bids from coastal cities?

Three weeks after we did a concert [version of Gold Mountain] at the NYC Times Center, I got emails from someone in San Francisco, someone in LA, and someone in Salt Lake City, all mentioning this 150th anniversary.

The SLC email came from the president of the Chinese Railroad Workers’ Descendants Organization, Judge Michael Kwan from Utah, and he said, “Would you bring the show here?” I said, “Of course!” Actually doing the show where the railroad was completed—they have such a strong connection to the railroad; it’s local history.

We had four performances, two in Salt Lake City and two in Ogden. The first night in Ogden, a group of 150 to 200 Chinese railroad workers’ descendants came as a group to see the show—they stormed the stage at our curtain call. They literally ran to the foot of the stage, screaming and yelling. It was crazy, and amazing. I mean, Chinese people don’t do that. Definitely not American-born Chinese. You know, we try to, like, keep our heads down and stay invisible. But they were not going to be invisible that night. They felt like their ancestors were finally seen.

What makes musical theater a good vehicle for bringing Chinese American history to life?

[American playwright, screenwriter, and librettist] David Henry Hwang has this line in his show “Soft Power” that musical theater is the perfect delivery system for empathy. The whole point of a musical, if you write it in the correct way, is that the audience jumps into the skin of somebody or some people on stage. You somehow completely open your heart to people, and have your heart broken as you watch them go through their lives. That will stay with you. And then you will also be more empathetic to people who come from very difficult circumstances, and just want a chance to overcome them. That’s my hope with a show like this.

Another reason why the show seems so relevant right now, I think, is that we’re having this big debate in this country about the role of immigrants and whether they are a plus or minus to society. You know, the Chinese Exclusion Act was law until 1943. Now we’re labeled as the “model minority,” but back then, we were unclean; immoral; lazy; drug dealing; drug using. All the same rhetoric we hear now [about immigrants]; it’s just word for word.

You point out that they are actually immigrants coming from distressed circumstances who have helped build the country—literally. And somehow, they managed to become Americans and not destroy the fabric of society. There’s something cyclical about xenophobia. It seems like, especially Americans, we keep needing to learn the same lessons over and over again.

So, I’d say that this story is for everyone. And it should be.

Photographs by Lia Chiang

“Scene Change” is a story from our issue, “High Steaks”. To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine. Alternatively, you can purchase the digital version from the iTunes Store.

Scene Change is a story from our issue, “High Steaks.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.