What it’s like to exhibit art in a disappearing urban village

In the decade that art critic Zhang Zongxi (张宗希) has lived in Caochangdi, he has gazed contemplatively at the freshly casted sculptures in art studios, bobbed his head to unplugged improvisations at reggae bars, and munched on lamb skewers at outdoor barbeque stands.

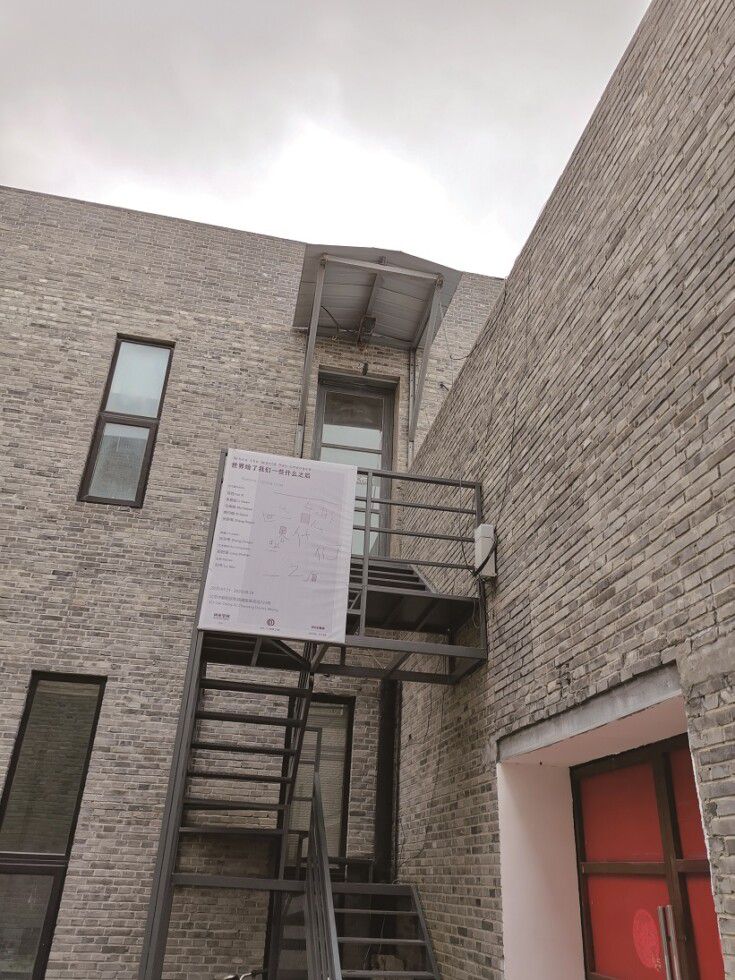

Under “urban renewal” demolitions and pandemic control measures, the dream that many avant-garde artists and cultural nomads had built in this bohemian Beijing suburb is now slipping away. Yet as Caochangdi’s maze of rough-and-tumble bungalows empty of the galleries, artist’s studios, and design firms that have put down roots alongside thousands of migrant workers, Zhang remains hopeful. Choosing to stay in what increasingly resembles a ghost town, Zhang opened his own gallery in July and gave it an auspicious name: Growing Space.

Growing Space is a 60-square-meter art space in Caochangdi’s maze of underground galleries

What is behind the name “Growing Space?”

Growing Space is the English counterpart of Ciye (词业), which was initially the name of a public WeChat account I started six years ago. As a freelance art critic, I always feel fragmented when I see my work scattered across the art world and my name attached to different publications. To establish a coherent identity, I started a WeChat account and republished all my writings under the name Ciye.

In Chinese, 业 usually appears in the names of commercial banks as a symbol of expanding wealth. If banks are supposed to add value to money, is there a place that adds value to words? That’s my wistful longing for the WeChat account and now the art space.

Like literature, art can be interpreted in the linguistic systems of grammar, syntax, and lexicon, as each artwork carries a series of signs that “speak” to the audience. Compared to Ciye’s literal translation, “Bank of Growing Words,” “Growing Space” leaves out the idiomatic implications and captures the upward mobility that I want to emphasize, especially during the current period of socio-economic stagnation.

Ma Haijiao, “Ma Guoqian,” 2016

How do you define the space?

It is first and foremost an exhibition platform. In the same way that the WeChat account consolidates my writings on a personalized website, Growing Space materializes them in a physical space.

Unlike the bigger galleries in Caochangdi bearing the financial burden of rent and daily maintenance even during the pandemic lockdown, Growing Space’s 60-square-meter room makes it more adaptable to the changing environment. Having lived in Caochangdi for more than a decade and been forced to move to a new apartment every few years under the village’s ongoing demolitions, I am prepared to shut down the space when the time comes. I can find another space or go back online, but the platform will live on no matter where it is.

Xi Danni, “Box No.2,” 2020

What are the challenges you are facing?

The gallery’s lease belongs to my friend who owns a print-making workshop in the back and is generous enough to allow me to use a portion of his space for exhibitions, but I still need to make the program financially sustainable to cover my expenses. Naturally, I would like to sell the artworks on display and make money through commission, but although I have acquired so many experiences in the art industry—from writing to film-making, from studio management to magazine distribution—selling art is not one of them. It has been difficult for me to learn from scratch, but having a space of my own makes everything worthwhile.

Growing Space is a story from our issue, “Disaster Warning.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.