The myth that inspired firecrackers and the color red for Chinese New Year

This is the tale of a creature that is inseparable from Chinese New Year, and that inspired some of its most basic customs…no, not the 12 zodiac animals, but the monster literally known as 年 (nián, year).

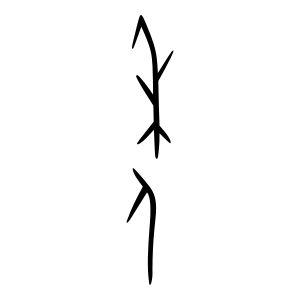

The habits of this beast are elusive: No ancient records of folk customs or mythology refer to it, and its entire legend seems to have been handed down orally. In the oracle bones, China’s oldest system of writing, an early form of the character 年 appears as a pictograph of a person carrying a stalk of ripened grain on their back. In the second century, it was written as 秊 (nián) and defined in the Analytical Dictionary of Words, China’s first dictionary, as “the ripening of grain”—no fantastic monsters there (or reference to any specific unit of time, for that matter).

The character 年 in the oracle script (Sinica Database/Public Domain)

Still, folk legends generally agree that nian is a monster that lives either in the sea or the forest, and comes out once a year on the night before the new year to wreak havoc on humankind. It is said to have a single horn on its head, sharp teeth, and a ferocious look in its eyes. It would go into villages to eat grain and destroy the homes, and devour any human or livestock that ran across its path.

There are several versions of the legend that explain how humans dealt with this yearly menace. According to one, long ago, a group of humans were preparing to evacuate their village on the night of nian’s visit, when an old beggar wandered into their midst. Everyone was too busy to pay attention to him, except for a kind old woman who served him some dumplings, and warned him eat quickly so he can escape to the mountains before nian arrived.

The old man, however, promised that if she left him in her house, he would have driven away the monster by the time she returned. Though skeptical, the old woman did as he said, and when the villagers returned the next morning, they found the old man gone but the village unharmed. The front of the woman’s house was papered with red streamers, and a few remaining firecrackers sounded a raucous welcome in the yard.

The villagers inferred that nian was afraid of loud noises and the color red, and began setting off fireworks and attaching “couplet” poems on red paper on their front door every New Year’s Eve.

New Year customs like setting off firecrackers and writing couplets on red paper were allegedly inspired by the legend of nian (VCG)

Another version of the legend states that the monster was actually known as 夕 (xī), and nian was a minor god dispatched by the Kitchen God to deal with xi by using firecrackers and bands of red silk. This is supposedly why the Lunar New Year’s Eve is known as 除夕 (chúxī), literally “eliminating xi.” The tradition of family banquets on Chuxi has also been associated with the monster: It’s said the whole family gathered together and barred their doors in preparation of nian’s visit. They would eat a sumptuous meal to symbolize their togetherness before the oncoming attack, and worship their ancestors to pray for safety.

However, for a legend that is supposed to have given birth to so many customs of the Spring Festival, it is odd that no traces of nian are found in ancient records—not even well-known bestiaries like the fourth century BCE’s Classic of Mountain and Sea (《山海经》).

Among the 277 of mythological beasts profiled in this classic, though, is a creature known as the 山魈 (shānxiāo), which has the face of a human, black fur, and makes sounds of laughter when it sees a person. The shanxiao live in the forest, and if a human wanders into their realm, they will take revenge by going into the village, playing tricks on the residents, and stealing their grain. Humans, in turn, would scare the shanxiao away by beating on gongs and setting off firecrackers.

Judging from this legend, the inspiration for xi and nian was probably the primates that competed with humans for habitat as their villages expanded into the wilderness. Predators like bears or tigers are unlikely models for nian, as they hibernate in winter. Regardless, the legend is a reminder of how close to nature humanity once lived—and how thankful they must have been to survive another year.

Cover image from VCG