An unlikely friendship with Chinese artist Zhang Chongren helped the creator of the Belgian comic strip defy stereotypes—in 1934

The Tintin comic series, telling the global adventures of the Belgian boy reporter, are world-renowned, but the reputation of its creator Georges Rémi (better known by his pen-name “Hergé”) has been taking a battering.

In 2007, the centenary of Hergé's birth, the UK Commission for Racial Equality recommended that Tintin in the Congo (1931) be withdrawn from sale due to its “hideous racial prejudice,” as it portrayed the Congolese as kindly but ignorant children in need of the white man’s governance. Chinese characters fared little better in the comics, depicted in Tintin in the Land of the Soviets (1930) and Tintin in America (1932) as dog-eating, pig-tailed thugs.

But just four years after the publication of Tintin in the Land of Soviets, Hergé's The Blue Lotus in saw a complete about-face in the artist's portrayal of Chinese people and culture. First published as a serialized comic strip in 1934, Tintin’s pursuit of a gang of international opium-smugglers through the dens and alleys of Shanghai is a nuanced and underrated dive into the city in the Republican era. Hergé’s detailed pen captures Shanghai’s turbulent politics, secluded opium dens, segregated International settlements, Sikh and British police enforcers, and riotously colorful banner-streaked streets. This U-turn was due to an unlikely friendship with the Chinese artist Zhang Chongren (张充仁), who became Hergé’s mentor and guide.

The Blue Lotus has a remarkably high 9.1 rating on Chinese review app Douban, with readers praising its nuance and sensitivity in portraying 丁丁 (“ding ding”, Chinese for Tintin) standing up for Chinese in the face of Japanese invaders. Although the Tintin adventures don't enjoy the same level of fame in modern China as they do in the West, thousands of reviews have been left on Taobao and JD.com praising Hergé's striking images, funny characters, and engaging plotlines, and for inspiring children to read.

As to why Hergé had decided on China for his next work after Cigars of the Pharaoh (ending in February 1934), he appeared to have little initial curiosity about the country. “I don’t know,” he explained to Zhang at the start of his Blue Lotus project in April 1934, when asked for his reasons for choosing China. “For a change of continent. [Tintin] has already been to Europe, Africa, America, and the Middle East. Never to Asia.”

When Le Petit Vingtième, the newspaper Hergé worked for, announced that Tintin's next adventure was going to take place in China, Father Léon Gosset, chaplain for Chinese students at the University of Louvain, contacted Hergé. Gosset told him of the popularity of the Tintin comic strip with his Chinese students, and how upset they would be if China was treated the same way Congo had been. “The best thing you can do is to find me a Chinese advisor,” Hergé responded.

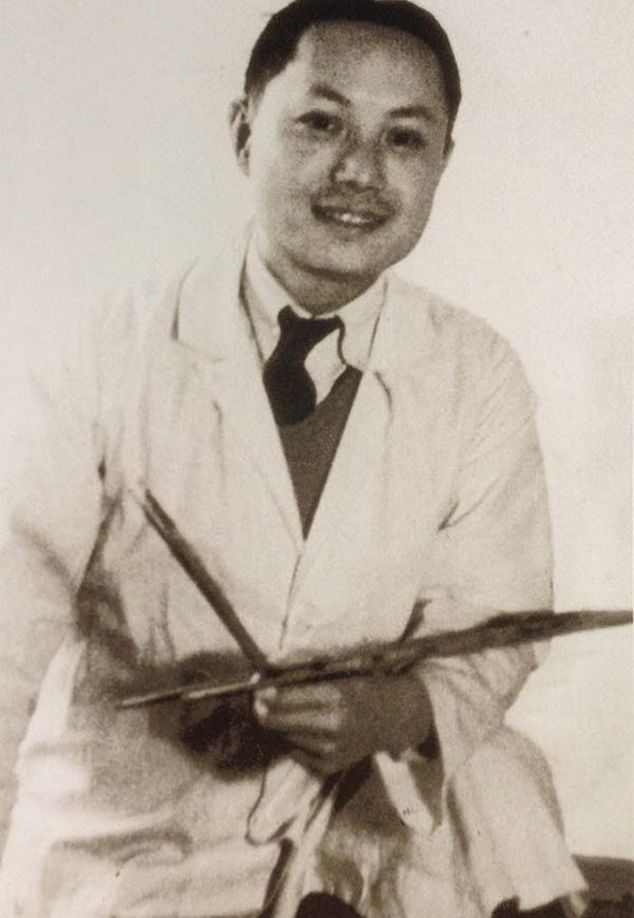

Gosset introduced Hergé to several Chinese students living in Louvain, and finally to Zhang in May 1934. At 26, Shanghai-born Zhang was only a year younger than Hergé, having traveled to Brussels to study at the Royal Academy of Beaux-Arts in 1931. He visited Hergé at his home every Sunday throughout 1934. Zhang taught Hergé traditional calligraphy and the basics of Daoist philosophy, and the pair conversed on Chinese current affairs and traditional culture (Zhang was fluent in French).

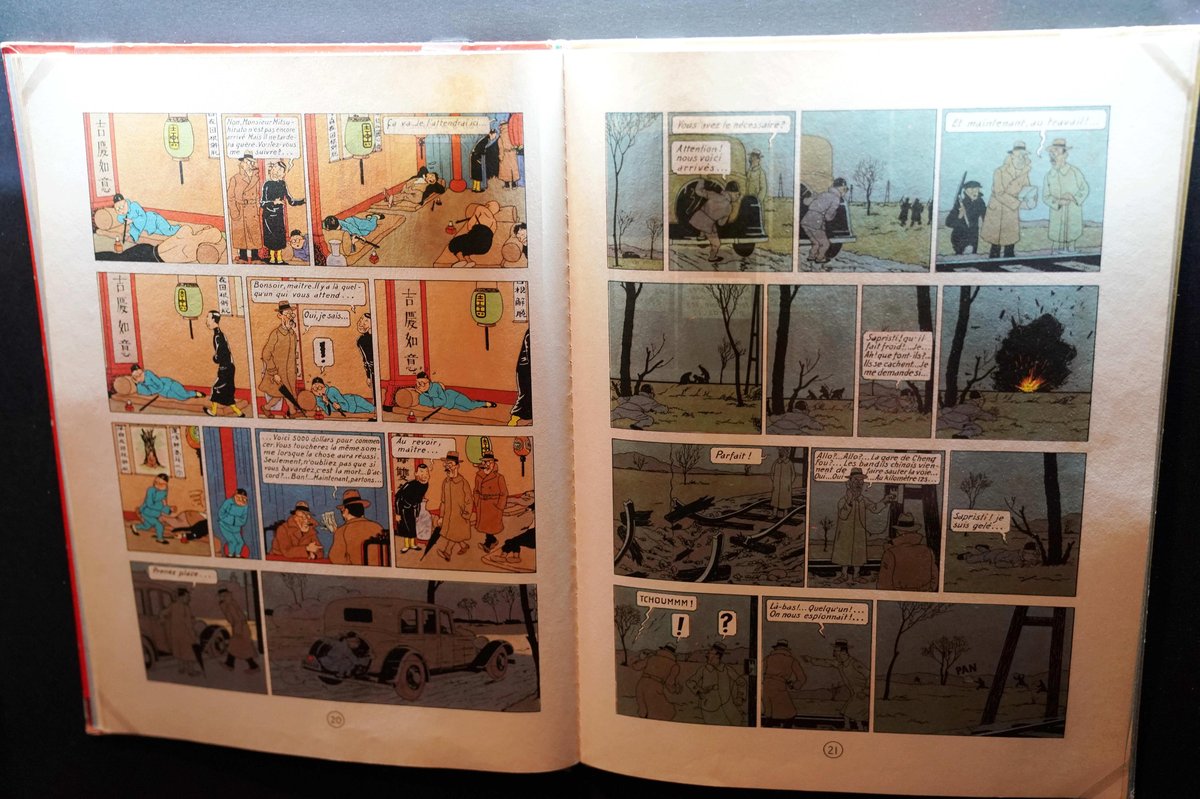

The Chinese phrases in the background of the comic strip, painstakingly written out by Zhang, lend extra depth for those who can read Chinese. Phrases written in clerical script from the Old Book of Tang, praising the virtues and determination of ancient doctor Sun Simiao (孙思邈), furnish the headquarters of the Sons of the Dragon, a secret society dedicated to fighting the opium trade. Ad hoc posters in many of the street scenes call for boycotts of Japanese goods and cry, “Abolish Unfair Treaties!” and “Down with Imperialism!”

Although Zhang had initially agreed to meet only as a favor to a friend and for the honor of his country, the two became firm friends. Zhang later told Pierre Assouline, Hergé's principal biographer, that the artist had offered to give him a co-creditation for the book’s creation. When Zhang refused (perhaps out of humility), Hergé suggested Zhang sneak his Chinese name into some of the shop signs Tintin passes by.

Zhang’s name was also given to Chang Chong-chen, a Chinese boy whom Tintin saves from drowning (and who in turn saves Tintin from being beheaded later in the book). Tintin’s meeting with Chang is an opportunity for Hergé to address the dehumanizing stereotypes Westerners and Chinese had of each other, both remnants of the conflicts of the late Qing dynasty (1616 – 1911). In the book, Chang's previous belief that “all white devils were wicked” is challenged when Tintin saves his life. Tintin counters that lots of Westerners still believed “all Chinese are cruel and cunning and wear pigtails, are always inventing tortures, and eating rotten eggs and swallows’ nests.” The reader can now be in on the joke when British detectives Thompson and Thomson think they have disguised themselves well as Qing mandarins, when in fact they've decked themselves out in outdated stereotypes that draw a crowd of Chinese roaring with laughter.

Hergé later admitted in an interview that “Zhang was, without knowing it, one of the principal influences on my evolution.” After this adventure, Hergé took care to make sure each place Tintin visited was thoroughly researched and true to reality. Hergé never traveled to the places he packed Tintin off to. According to Assouline, he rarely even left his native Brussels. But whereas before The Blue Lotus, Hergé's material had simply been harvested from the crude images he encountered on a daily basis in magazines, newspapers, and films, now he would source news stories and photographs, keeping them in a filing cabinet for later reference. Tintin would no longer rely on imperialist stereotypes, paying such attention to detail that the great anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss stated that "Tintin was the comic strip that was the most respectful of world cultures."

Zhang’s fury at the Japanese made its way into the book, where fiction imitates reality. The infamous Mukden Incident of 1931 (when the Japanese blew up a small stretch of railway line and falsely blamed it on Chinese saboteurs, using it as an excuse to invade Manchuria) features prominently in the comic, with their complaint against Chinese saboteurs taken all the way to the League of Nations.

Remarkably, Tintin defends the Chinese not only from Japanese aggressors but bullying Western businessmen—according to Sian Lye in her book The Real Hergé: The Inspiration Behind Tintin, “this sent out a clear anti-racism message, which was revolutionary at this time in Belgium and directly contrasted with the other comic strips in the country.” There was also an anti-Imperialist streak in an American businessman named Gibbons, beating a Chinese waiter for spilling a drink and calling him “yellow scum” while absurdly declaring they should be learning the “manners” of our “superior Western civilization.”

But Hergé isn’t perfect. The crass caricatures of Chinese that Qian Zhongshu (a prominent novelist and literary scholar of the interwar period) once described as “a snub nose, two slanted slits for eyes, and eyebrows so high up and removed from the eyes that the eyebrows and the eyes must have pined for each other,” are transferred to the Japanese baddies. A fairly easy way to spot a Japanese character in this book is to see which East Asians have extra-long teeth, are dressed in ill-fitting European clothes, and have a childish inability to do anything effectively.

The Japanese issued the newspaper with a formal notice of complaint and its ambassador to Belgium demanded the book be banned. But Zhang reassured Hergé that “if the Japanese are angry it’s because we are telling the truth.” The comic strips were an instant success among Father Gosset’s students, and earned Hergé an invitation from First Lady Song Meiling (宋美龄) to travel to China in 1939, but the outbreak of World War II prevented him from doing so.

But the use of stereotypes against the Japanese in the comic strip, despite Hergé’s new friendship, is a reminder of the difficulty of eradicating prejudices against East Asians. Without Zhang's humanizing influence, it is easy to imagine The Blue Lotus simply becoming a tale of Tintin foiling a group of pig-tailed Chinese opium dealers. There is also no escaping the “white savior” element of Tintin becoming the lynchpin of the Sons of the Dragon, without whom the organization was unable to achieve their goals. The book also ends with Chinese crowds parading banners with Tintin's face through the streets.

There are also drawbacks to Hergé’s limited source materials, his view of China arranged through selected photographs and Zhang's Shanghai-based view of inter-war China. Shanghai’s more modern elements (like the Bund) are missing, while the traditional old city walls feature heavily even though they had mostly been demolished in 1912. There is also no mention of the civil war with the Communists.

Zhang left Brussels in September 1935, eventually returning to China at the orders of his family. According to his interview with Assouline, he remembered a tall man sprinting into the station as the train moved out of Brussels station, waving his handkerchief. Tintin and Chang have a similar farewell in The Blue Lotus—parting with Chang is one of the few times that Tintin is seen to cry in the whole series. Zhang went on to establish a successful art school in Shanghai, and wouldn’t see Hergé again for the next 40 years, only reuniting with his old friend in 1981 in an event organized by the Belgian government. But during that time Hergé never forgot Zhang—“I so desperately want to go to China and find my friend Chang” he wrote to a journalist friend, Dominique de Wespin, in 1939, when he heard she was traveling to China. He also had a worried Tintin searching for the lost Chang in Tintin in Tibet (serialized in 1958), written during Hergé's battle with depression. Although separated, Hergé yearned for the company of the man who had, according to Pierre Assouline, made him “come into his own.”