A Silk Road legacy lies in the Hebei wilderness

About two hours’ drive from the city of Zhangjiakou, Hebei province, the signposts stop. A single-laned concrete road winds through shallow loess valleys on the southern edge of the Mongolian plateau. The horizon is empty save for a few small settlements scattered every two kilometers, the sole representatives of humanity.

Our target is somewhere in these valleys, but aside from one signpost off the main road reading “Xichengyao Cultural Temple,” we rely on directions from passing locals, finally arriving at our destination just before sunset.

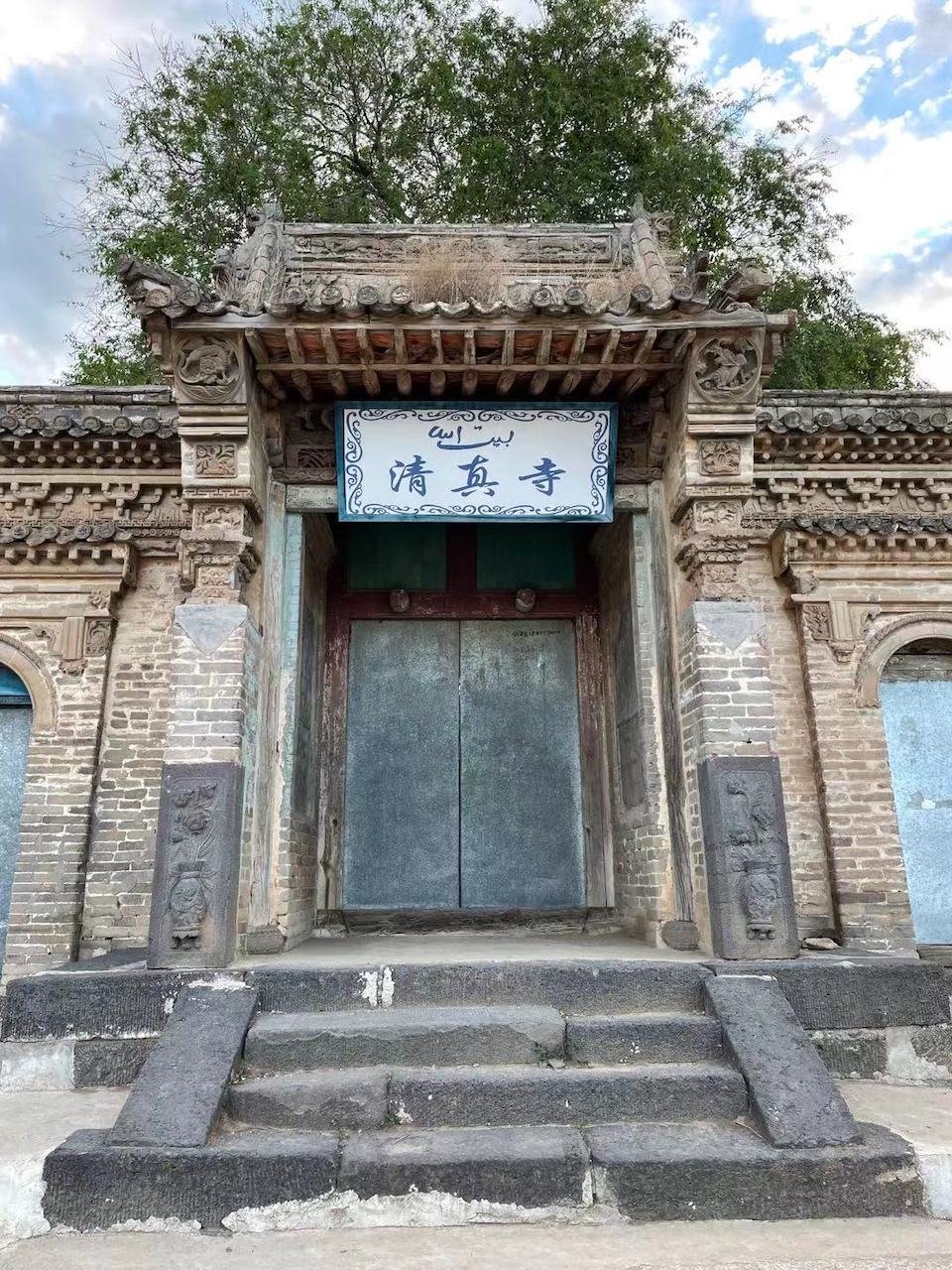

The Xichengyao (西城窑, lit. "Western City Kiln") Temple stands on the southwestern edge of a village by the same name in Shangyi county, Zhangjiakou, giving a spectacular view over a dried riverbed. It’s a remarkable edifice to stumble on this far in the sticks—a mosque fusing Chinese and Islamic architectural styles.

The exact history of the mosque is hard to come by, but according to the Shangyi county's government website, it seems to have been built by a Hui community sometime in the reign of the Qianlong Emperor in the Qing dynasty (1616 – 1911), between 1735 – 1796. The Hui are a Muslim ethnic group with a population concentrated in China's northwest (Gansu, Ningxia, and Xinjiang), forged with the arrival of Islam into China along the Silk Road in the Tang dynasty (618 - 907). Hui communities—comprised of descendants of Arab and Persian merchants who intermarried with Chinese, and sometimes converts from other ethnic groups—formed all around China in subsequent centuries. In Hebei, it was estimated that they constituted 0.82 percent of the province's population as of 2010, according to a paper titled "Study on Current Muslim Population in China" by Yang Zongde.

This land was frequently the site of skirmishes and battles between the forces of the Qing and local inhabitants—perhaps this was why the mosque is recorded to have been burned by Qing soldiers in 1890, when the systems enforcing law and order began to weaken in the Qing state in the late 19th century.

Mosques of ancient China took on a variety of guises depending on the region and time period. Some are Arabic in style, like those of the northwestern Gansu province and Xinjiang region; or in the southeastern port cities of Guangzhou and Quanzhou, providing a taste of home for the Arab traders who arrived by sea during the Song dynasty. By the Ming and Qing, the Hui sought to blend into Chinese communities, adopting Han language, ethics, and lifestyle—done for "mere survival," according to Professor Gui Rong of Yunnan University, in the face of stricter laws passed by these dynasties to bring about assimilation (the Qing forced them to wear queues, for example). Mosques built during these later dynasties are lifted straight from the playbook of Chinese architecture: the Niujie mosque in central Beijing has a pagoda as its minaret, and although the Great Mosque of Xi'an has the layout of a mosque, its buildings bear the gabled and tiled sweeping roofs of a Daoist temple.

The mosque at Xichengyao is a beguiling hybrid, a reminder of the Hui's dual Islamic and Chinese identity. It has the winged eaves, curving roofs, and courtyard layout of a Qing home. The rooms are only accessible from the interior of the courtyard, while the prayer hall occupies the side directly opposite the courtyard door, traditionally the place reserved for the most important room.

Yet it makes its Islamic credentials known: the building ignores the traditional feng shui of being built on a north-south axis, facing west towards Mecca. Typical ornamentation like geometric motifs and extracts of Arabic script decorate the exterior and roof tiles. Xiyaocheng's gray bricks and distinctive architectural blend recalls the Bukui Mosque, almost 1,500 kilometers away in Heilongjiang in China’s northeast, also built during the Qing dynasty.

Today, the courtyard lies empty, the old prayer hall now disused and dilapidated. However a community still worships in the village—a new imam arrived last year, fresh from the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, responsible for administering to the Muslims among the village's 82 listed Hui households. Many use the old mosque as a bathhouse to wash in preparation for worship at a newer mosque in the village to the north.

Back in 2014, the county government included the mosque in a list of the cultural attractions of the local Taolizhuang township, "an excellent tourist haven that needs to be developed urgently," hoping to use these sites for an eco-tourism drive to "promote ethnic unity...and economic prosperity." Zhangjiakou itself is set to become the site of China's Winter Olympic Games shortly in 2022. The concrete road, two solar-powered street lamps, and a shiny new hotel (hurriedly unlocked as our car arrives) are the fruits of such investment.

But for now, cattle low in courtyards behind ramshackle wooden gates beside the mosque, stray dogs run across the deserted roads, and a donkey snorts from a muddy paddock the other side of the riverbed. None of the township's sites are listed on Xiaohongshu, the essential app to turn a site into something viral. Perhaps they are just too far out of the way to draw the crowds the government craves—as the sun sets, no lights can be seen beyond the mosque in the dark valley beyond.