China has 20 million sign language users, but regional varieties and misguided policies mean they still struggle to communicate

In a crowded classroom, artist Bai Fengxiang is lecturing more than 100 university students. His hands flit across the projector screen, making various shapes and gestures to convey the notion of a large canvas: 3 meters high, 8 meters wide.

“That action was very difficult to paint. A hearing person gave up halfway. I picked up and kept painting until it was done. The hearing person was speechless,” Bai signs with a proud grin and a thumbs-up. So were his students, at least outwardly—Bai, as well as his listeners, are all hearing-impaired.

This passionate lecture, captured by the documentary Era of Sign Language (2010), is one of many that have brought the lives and communication styles of China’s hearing impaired to the big screen in recent years, courtesy of director Su Qing. Su, who is hearing, acquired sign language in childhood from his older brother, who lost his hearing due to antibiotics used to treat a fever in early childhood, as well as from the deaf community in their hometown of Baotou, Inner Mongolia.

Driven by a desire to tell the stories of deaf people in China who remain mostly unseen and unheard, Su set out to visit the hearing-impaired around the country and film moments from their lives in 2001. This later culminated in several internationally screened documentaries, including also White Tower (2004) and Caro Mio Ben (2018).

But soon after he set out on his journey, Su started to have problems in communication. “Previously, when I communicated with my brother and his friends, I could understand almost everything, so I was surprised to find that in Shanghai, for example, I couldn’t understand a lot of what [my interviewees] signed,” Su told TWOC over the phone. He sometimes had to resort to writing for communication before resuming shooting.

In the same way the spoken language known as “Chinese” has 129 recognized dialects, many of them not mutually intelligible, Chinese Sign Language (CSL) is also just an umbrella term covering the different regional varieties of sign language used by over 20 million hearing-impaired people in China, consisting of hand gestures, facial expressions, finger spellings, and body postures to convey meaning.

The term 手语 (“hand language”), for sign language, first appeared in Chinese records in the Tang dynasty (618 – 907). In the Records Under the Autumn Lamp on Rainy Nights(《夜雨秋灯录》), a collection of short stories by novelist Xuan Ding (宣鼎) published in 1877, a deaf man and his hearing mother are able to convey simple messages to each other by signs such as a flat palm representing fish, while a hearing pawnshop owner shows his ring finger to the deaf man to signal “mother,” a sign apparently commonly understood.

However, there were no formal deaf schools or fully documented sign languages in China until 1887, when American missionary Charles Rogers Milles and his wife, Annette Thompson Milles, founded a school for the deaf in Yantai, Shandong province. Although the school adopted the oralism method, teaching students to read lips and speak by mimicking mouth shapes and breath patterns, a sign language naturally emerged among the congregation of deaf students.

In 1892, the second deaf school in China was founded in Shanghai by French Jesuits, which also educated deaf orphans with oralism. But because it recruited deaf students from local families who were already signing, the students soon began to communicate by sign language outside of class.

Since then, with the establishment of more deaf schools, as well as deaf communities, a multitude of local sign languages have developed across the country and transmitted from older students to younger ones, according to Dr. Yang Junhui, an expert on deaf education who teaches at the University of Central Lancashire in the UK.

Today, there are two main varieties of CSL: the North regional variety, which has more influence from spoken Chinese, and the South regional variety, which employs more visually-derived signs and facial expressions.

Many regional variants exist under these two large categories, with the main ones usually named after major cities, including Beijing, Shanghai, Nanjing, and Chongqing, where deaf communities and schools for the deaf are both well-established. Even within the same city, graduates of different deaf schools can sometimes be identified by the differences of their signs, noted Yang in a 2015 paper.

Between the local sign languages of Beijing and Shanghai, even the most basic vocabulary words can differ, including those for family members, dates, and places. For example, the Beijing sign for “Lhasa” mimics the action of turning a prayer wheel commonly used by Tibetans, whereas deaf individuals in Shanghai would make a steeple shape with both hands, before moving the two hands away from each other with the thumbs and pinkies extended outward, evoking the temple roofs in the Tibetan capital.

Efforts to standardize CSL started in the late 1950s, in the same spirit as the movement to promote Mandarin, or Putonghua, across the country, according to Yang. But some attempts were in fact imposing spoken Chinese onto CSL.

The China Association for the Blind and Deaf began standardizing CSL in 1957, publishing a lexicon of standard signs in 1961, and several updates in the following decades. According to Guokr, a Chinese website on science and technology, the standard reference book includes many words based on fingerspelling pinyin, which is not intuitive to many deaf people as it transcribed the sounds of spoken Mandarin. A number of researchers have observed the standard variety of CSL is not popular among deaf communities, and many deaf people aren’t able to understand the sign language interpretation that accompanies news programs on TV.

In addition, the standard reference books only cover vocabulary and do not explain the grammar of CSL, which often has a different word-order from spoken Chinese. As a result, many hearing teachers trained in standard CSL lexicon sign using the syntax and morphology of spoken Chinese, or what is known as Signed Exact Chinese. Su, who attended classes at the local deaf school with his brother, remembers that a teacher, whose first language is not sign language, would use four to five gestures to indicate “please open the book,” whereas in the students’ first language, only two are necessary: “book” and “open.”

Yang observed that sign language has traditionally been viewed as a problem for deaf students that impedes their fluency in Chinese. In the 1950s, deaf education in China adopted the principle of “spoken language as major means, and sign language as auxiliary” under national guidelines, which means that deaf schools taught predominantly with oralism, with CSL and Signed Exact Chinese used as additional means of communication. While CSL still circulated among students, it was rarely used as a language of instruction, wrote Yang.

Most deaf individuals TWOC spoke to say that regional sign language differences are fairly easy to pick up. What is more difficult and disheartening is communicating with hearing individuals and the lack of an inclusive attitude from the hearing-dominated world. “Many hearing people don’t recognize sign language as a language,” said Mei Xiaosheng, a teacher, in one of Su’s documentaries. “They think deaf people are talking nonsense and [therefore] look down upon them.”

Another interviewee in the documentary said he had difficulty understanding the names of illnesses during hospital visits: “It’s best to have a hearing person who can interpret for me, but my children are busy, and hiring a sign language interpreter costs money…so we often have to bear the pain by ourselves.”

Covid-19 has presented new challenges for those who lip-read. “During the pandemic, everyone wears masks, so I can’t read lips to understand what they are saying,” Wang Wenting, a deaf designer, messaged to TWOC over WeChat.

In recent years, there is an increasing recognition of CSL as a full-fledged natural language, partially under the influence of deaf education philosophy from the West, noted Dr. Yang. The first experimental class on sign-bilingualism was piloted in Nanjing in 1996, using an international approach that teaches children both sign language and the written and spoken forms of society’s dominant language. This approach uses CSL as the language of instruction, rather than presenting it as subordinate to Chinese or a tool to assist teaching the spoken language.

In addition, a new state-issued book of standard lexicon was published in 2018. Not only does the new reference book include a lot more entries, but it also takes a more descriptive approach that attempts to capture how CSL is currently used among China’s deaf populations, instead of dictating how it should be used.

According to Guokr, deaf people made up three-fourths of the committee tasked with creating the new reference book. The committee invited sign language users from around the country to discuss optimal expressions for concepts.

As reported by the Beijing News, the new lexicon removes a number of pinyin-based words that caused confusion, and when regional differences are significant, especially between the North and South varieties, the book would list them all instead of making arbitrary choices.

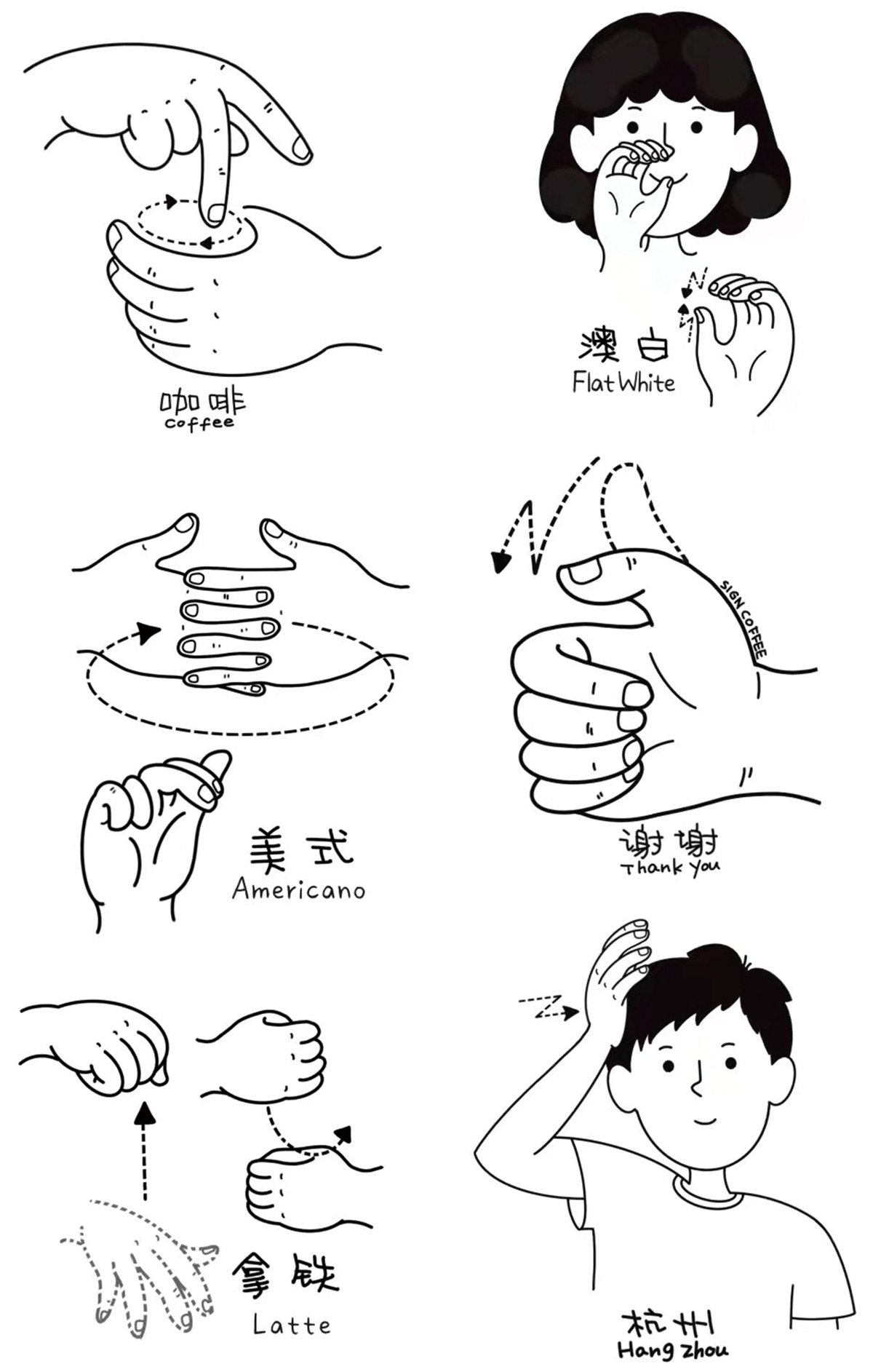

While it remains unclear whether the Putonghua equivalent of CSL will permeate the whole country as Putonghua has done, some places have worked out their own solutions. In the sign language cafe in Hangzhou owned by Yang Di and her husband, illustrations on the walls showcase signs from both the Hangzhou dialect and the national standard.

Su, while continuing to make documentaries, has opened a restaurant in Beijing with his partner and co-director, where CSL is the lingua franca. With hearing-paired employees who come from all over the country and use different signs for food like eggplant, chocolate, and garlic, communication is sometimes an issue. Some items are particularly easy to confound: When one signs “sour” to mean vinegar, another might understand it to be plum juice.

“We set a standard for menu items and basic service language so that there would be no miscommunication,” Su says. “As for the rest, for deeper exchanges, [the employees] will slowly adapt to one other.”

This is a story from our issue, “Access Wanted” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine. Alternatively, you can purchase the digital version from the iTunes Store.

Signs of the Times: Why Chinese Sign Language Users Struggle to Understand Each Other is a story from our issue, “Access Wanted.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine.