How rulers and would-be rulers used and manipulated prophetic texts

From celestial phenomena to successful harvests, auspicious signs from heaven were a must for any ruler in ancient China. One of the surest ways to sure up legitimacy for a ruler, or prospective ruler, was to make predictions about the future, with emperors often seeking knowledge of future happenings from sages, divinators, and officials in order to legitimize their rule.

Some proved more prophetic than others: Military strategist Zhuge Liang’s (诸葛亮) Divination Before Wars (《马前课》), written during the Three Kingdoms period (220 – 280), successfully predicted a number of events over the next thousand years, including that a king would emerge from the east of the Yangtze River—Sima Rui (司马睿) took the crown in the Eastern Jin dynasty (317 – 420)—and that a female emperor would arise in the fourth dynasty after the Three Kingdoms, which Wu Zetian (武则天) did in the Tang dynasty (618 – 907).

Prophecies could come from books supposedly gifted by gods, leaves with messages written by worms, or pieces of silk with mysterious characters on them. Here are some influential prophecies from Chinese history:

Hu will destroy the Qin dynasty

The paranoid first Chinese emperor Qin Shi Huang was desperate to avoid death, and sent a number of alchemists on quests to find him an elixir of eternal life in 215 BCE. Most never returned (presumably because they hadn’t found the key to everlasting life), but a man named Lu Sheng (卢生) did. Instead of an elixir, he offered the emperor a book called Notes of Prophecies (《录图书》) that he claimed to have received from an immortal during his trip. The book noted that a man named Hu would destroy the Qin dynasty. Terrified, the emperor interpreted the threat as coming from a northern tribe known as the hu people, and ordered his general to crush the barbarians and build a vast wall to defend his state. None of this worked, however, as just 15 years after the first unified empire of China formed, Qin Shi Huang died and the state collapsed.

Avoiding ghosts at “Gold Mountain”

Qin Shi Huang followed the advice of other prophets too. In 210 BCE when the emperor passed Jinling (present-day Nanjing) during his fifth national tour, his accompanying alchemists warned him that there were spirits of kings in the area and that someone might use these spirits to take the crown in 500 years‘ time. The legend stemmed from as early as the Eastern Zhou dynasty (770 – 256 BCE) when king Wei of Chu apparently buried tons of gold in the region (giving the the area its name “Gold Mountain”).

According to the Local Chronicles of Jiankang in the Jingding Period (《景定建康志》), a historical text written by Zhou Yinghe (周应合) during the Song dynasty (960 – 1279), the emperor was quick to react, and ordered a mountain in the area to be broken down to alter the fengshui and bring water from the Yangtze River flowing into the area, to show he could control the spirits of the region. The emperor also renamed the area Moling, which referred to a place for raising horses, to reduce its fame.

A prediction from the belly of a fish

After the death of Qin Shi Huang, his favorite son Hu Hai (胡亥) took the throne. Hu was known for his cruelty, and sentenced 900 of his own soldiers to death in 209 BCE after they failed to arrive on time after marching from Yangcheng (present-day Dengfeng in Henan) to Yuyang (present-day Miyun in Beijing) in defense of the region.

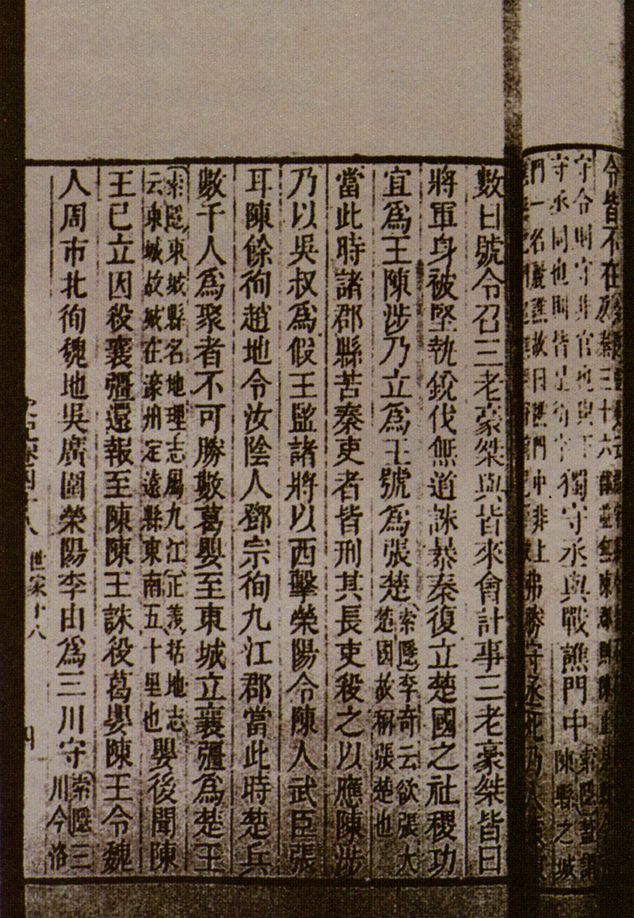

Two army officers, Chen Sheng (陈胜) and Wu Guang (吴广), decided that rather than accepting their fate they would launch a rebellion. According to Records of the Grand Historian (《史记》), in order to gain support from others Chen and Wu planted a prophecy for their soldiers to find. They wrote on a piece of silk “Chen Sheng will be the King,” placed it in the belly of a fish, and then allowed the fish to be found by one of their soldiers.

At the same time, Wu hid in a nearby temple and wailed “the Kingdom of Chu will flourish, and Chen Sheng will take the throne.” Spooked and convinced, the soldiers quickly took up arms for Chen and Wu’s cause, with Chen quickly declaring himself the prince of the former Chu kingdom (which had been destroyed by the Qin during the Warring States period). In just a few months, their forces grew to tens of thousands of men, and wreaked havoc across the Qin empire. However, Chen and Wu proved poor leaders, quickly corrupted by money and power, and undermined by mutiny in their own ranks, and were eventually defeated by the Qin forces.

Better listen to worms

According to the Book of Han (《汉书》), in 78 BCE, during a period of great infighting in the imperial court over who would success Emperor Zhao of Han, a dead willow tree in the imperial garden suddenly revived with leaves that carried prophecies etched onto them by worms. The characters read: “Gongsun Bingyi will wear the crown.” A court official named Sui Hong (眭弘) held the leaves, saying that there would be a person surnamed Gongsun who take the throne. Sui then submitted his discovery to Emperor Zhao, suggesting he take heed of the signs, look for this person, and then abdicate in the chosen one’s favor.

Sui’s words infuriated the then prime minister Huo Guang (霍光), who had Sui executed on the spot for spreading rumors. But five years later, when the Emperor Zhao died, Huo quickly switched his support from Liu He (刘贺) to Liu Xun (刘询), who became Emperor Xuan of Han. Liu’s original name was, of course, Bingyi. “Gongsun,” on the other hand, could be interpreted as meaning “grandson of a lord,” and Liu Xun turned out the grandson of a former prince, Liu Ju (刘据). Prophetic indeed...