Exploring the ancient Chinese obsession with carving messages and poems on rocks and walls

Every year, tourists cause controversy by carving graffiti on China’s renowned ancient sites. In June, a 41-year-old tourist surnamed Chong used a key to scratch his name into the side of the Great Wall. When another tourist videoed his behavior and posted it on the social media platform Weibo, the police soon tracked Chong down, detained him for five days, and fined him 200 yuan for damaging cultural relics.

Before that, in May 2013, a Chinese tourist surnamed Ding was widely criticized for carving “I was here” on relics at Egypt’s Luxor Temple, built around 1,600 BCE. In September 2015, a couple engraved their names and a heart on a bronze jar in Beijing’s Forbidden City, and in 2020, a tourist carved three messages into a 600-year-old wall in the capital’s Temple of Heaven.

But while this type of vandalism isn’t unique to China (a British couple was caught using a key to scratch “Ivan + Hayley 23” onto part of Rome’s ancient amphitheater in June this year), carving messages into walls has a distinct history in the country.

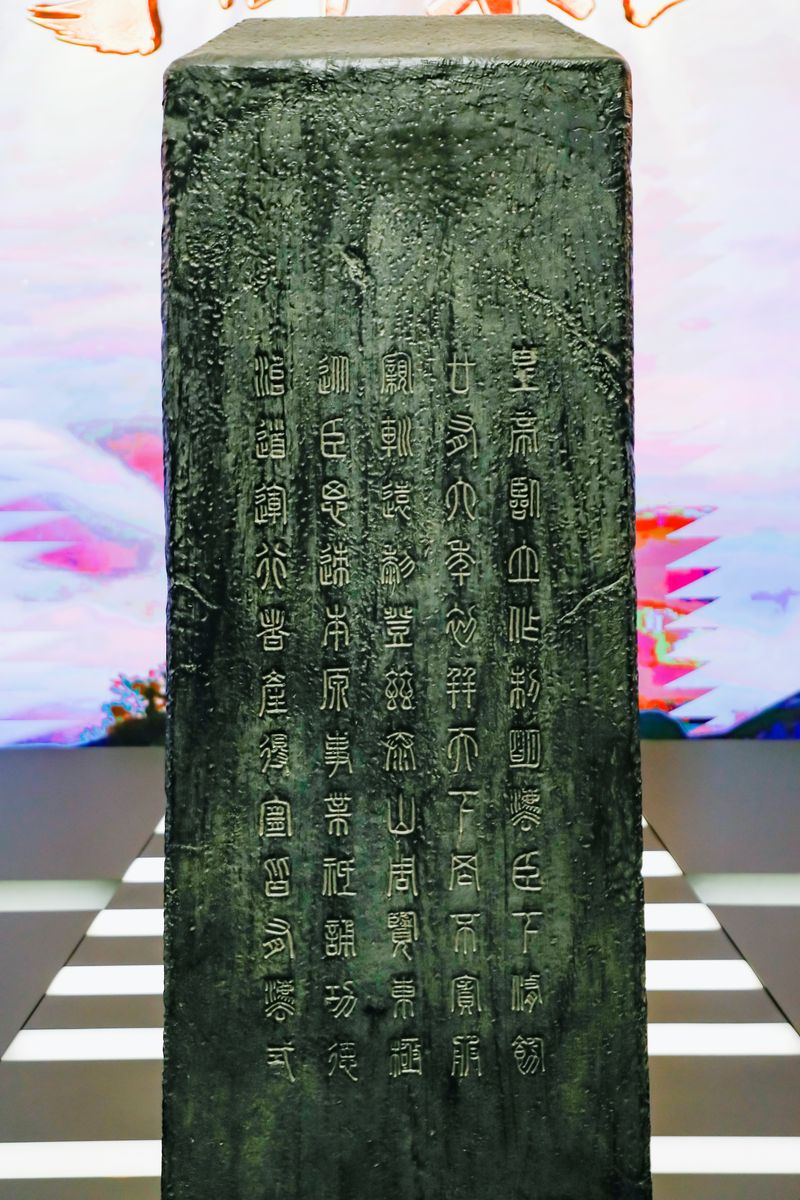

In ancient China, stone carvings were used to spread messages and showcase power and glory. Emperors and military generals used stone inscriptions to record their achievements; religious leaders etched their beliefs to attract more followers; and literati wrote poems or essays in hopes that their works would be remembered and passed on. Today, inscriptions from thousands of years ago are still visible on holy mountains and ancient relics in China.

According to the Records of the Grand Historian (《史记》), in 219 BCE, Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of a united China, performed rituals and sacrifices atop Mount Tai (in Shandong province) and carved an inscription on the mountainside. At the summit, Qin Shi Huang recorded his achievements on a rock: “The emperor ascended the throne, formulated wise systems and laws...after conquering the world, he never ceased governing.”

Since then, emperors regularly left inscriptions on Mount Tai as permanent symbols of confidence in their rule and power. In the following dynasties, countless emperors, officials, literati, and tourists have carved messages on Mount Tai. Today, over 2,000 inscriptions are still visible on the mountain, including several of Mao Zedong’s poems carved in the 1960s.

Carvings to commemorate the victories of Eastern Han dynasty (25 – 220) military officer Dou Xian (窦宪) became so well-known that the inscriptions birthed a chengyu common in today’s China. In the year 89, Dou won a decisive battle against the nomadic Xiongnu Empire in the Yanran Mountains (today’s Khangai Mountains of Mongolia). Historian Ban Gu (班固), who was a soldier in Dou’s army, composed an essay to record the battle, and Dou ordered it to be carved on the cliff face. The phrase “Carving a stone in Yanran (燕然勒石)” has since become a commonly used idiom, symbolizing the highest achievement for military generals.

Poets and scholars also began to carve their works into stones and later to paint them onto walls. According to the Book of Jin (《晋书》), a Han-dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE) calligrapher named Shi Yiguan (师宜官) was renowned for writing on walls. He would often visit taverns carrying no money for drinks, instead doing calligraphy with a brush and ink on the walls of the pub in return for money. Sadly Shi’s works didn’t survive today because as soon as Shi made enough money to pay for the drinks, he would wash his work away.

When poetry bloomed during the Tang (618 – 907) and Song (960 – 1279) dynasties, it became a prevailing trend among poets to write on walls, exhibiting their work to the public. At temples, restaurants, teahouses, inns, academies, or tourist attractions—any wall could become a stage for talented writers. Some places would even invite famous poets or calligraphers to leave works, known collectively as 题壁诗 (poems written on the walls), at their establishments. Wood boards called “poem plaques (诗板)” were prepared at many places for the poets to write on. According to the Tang-dynasty text Friendly Discussions from Yunxi (《云溪友议》), there were over 1,000 poems written on the walls at the Shennü Temple of Mount Wu in Chongqing at the time.

However, the wall writings weren’t welcomed everywhere. Monks at Ganlu Temple in Jiangsu province complained about the number of writings on the wall which meant they were constantly repainting their home.

At a time when print and paper were luxuries, writing on walls was an effective way for poets to circulate their works. Modern scholar Cao Zhi analyzed the trend in his 2015 book The Origin of China’s Printing Technology: “The task was simple: One just needed to write his work on a wall. Passersby from all corners of the world could read and copy it, and they could spread your work far and wide.”

Over time, poets would interact with one another through the verses they wrote on walls. They might leave comments on previous works or write poems responding directly to existing ones. When legendary Tang poet Li Bai (李白) visited the Yellow Crane Tower, a landmark in Wuhan, Hubei province, he intended to add his verses to the tower’s “poem board.” But first, he came across a masterpiece by another poet, Cui Hao (崔颢), titled “Yellow Crane Tower,” already inscribed on the wall:

The sage on yellow crane was gone amid clouds white.

To what avail is Yellow Crane Tower left here?

Once gone, the yellow crane will ne’er on earth alight;

Only white clouds still float in vain from year to year.

By sunlit river trees can be count’d one by one;

On Parrot Islet sweet green grass grows fast and thick.

Where is my native land beyond the setting sun?

Translated by Xu Yuanchong (许渊冲)

Li Bai was so overawed he believed there was no way he could better Cui’s effort. So he only left a simple message: “There’s a scene in front of my eyes that I can’t describe because Cui Hao’s poem is already there.”

However, the downside of writing poems on walls or carving them into rock is that they couldn’t be erased. According to the Selected Works of Poetry (《诗人玉屑》), a work about poetic theory composed in the Song dynasty, famous prime minister and poet Wang Anshi (王安石) harbored deep regrets about the sub-par poetry he wrote on walls when he was young. Wang had written a poem on the wall of the Cijun Pavilion in Jinling (today’s Nanjing, Jiangsu province), but later judged it a poor effort. In his later years, Wang visited the pavilion with his friend again, found the poem, and said: “When I was young, I wrote this poem. Once it’s spread, it can’t be changed...This should be a warning for young people who want to write a poem on the wall.”

That’s not as dire as the fate that befell Song Jiang in the Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644) novel Outlaws of the Marsh (《水浒传》). In the story, Song was exiled and had his face tattooed as punishment after mistakenly killing someone. One day, he drunkenly wrote a poem on the walls of a tavern to vent his sorrow. He was soon reported to the authorities as his poem was believed to express his desire to rebel. Song was promptly arrested. It’s best to think twice before writing so boldly in a public place.