From swimming across the Yangtze in the 60s to indecency scandals in the 80s: 30 years of swimwear history in China

On July 16, 1976, Huang Yang and his classmates left school and walked 10 miles to the Xunbiela River. They weren’t just skipping school. They had a purpose. On that day, thousands of people all over China were doing the same thing: swimming.

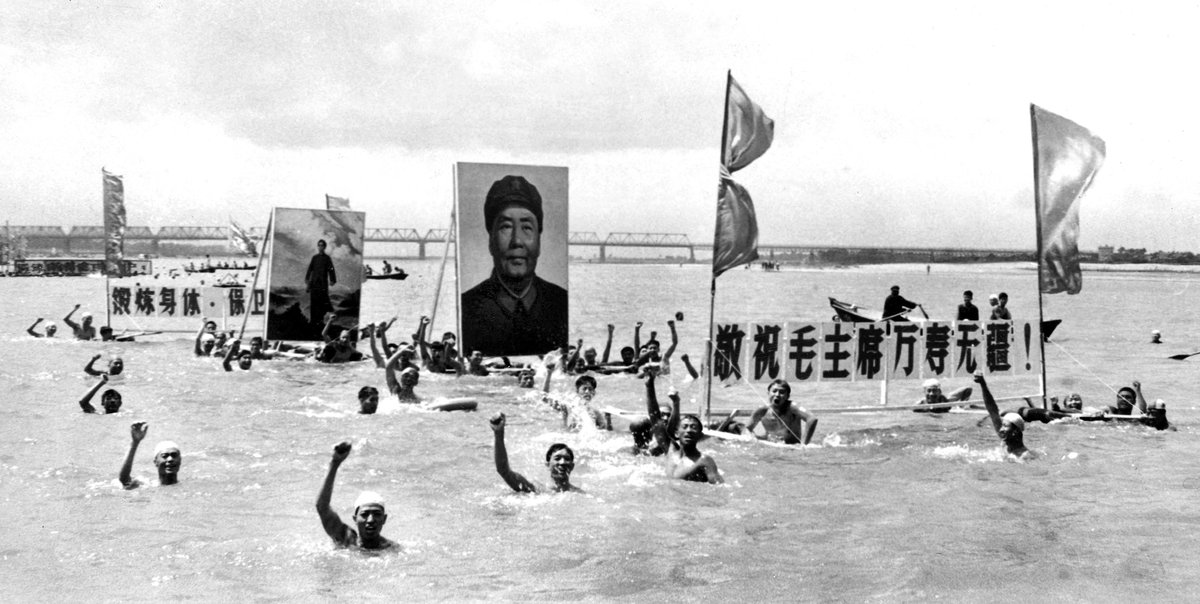

In the city of Wuhan alone, 5,000 people paraded to the Yangtze River. They were soldiers, factory workers, and students, and they all swam. The surface of water was adorned with red flags and propaganda banners.

The soldiers, holding their guns above their heads, swam in uniform and turned their pockets inside out so they wouldn’t fill with water.

Similar celebrations took place in all swimmable waters across the country, from the Pearl River in southern China’s Guangdong province to the Kunming Lake in Beijing’s Summer Palace.

These aquatic celebrations commemorated Mao Zedong’s final swim in the Yangtze River on July 16, 1966, when he was already 73 years old. At that point, he was still the most influential swimmer in China.

In 1956, Mao famously swam across the Yangtze River thrice, a feat immortalized in his heroic poem: “However hard the wind blows and the waves hit, I feel like I’m taking a casual walk in a peaceful courtyard.”

Mao was always a revolutionary, even when swimming. “Swimming is a sport that fights the power of nature,” he said. “We should all exercise in rivers and seas.” After hearing this declaration, everyone swam. In the culture of the time, swimming meant you were brave, that you could endure hardships, and also that you had a great, revolutionary spirit.

Some of these inspired, patriotic swimmers jumped into the water wearing nothing at all (at least, the men did). Back then, swimsuits were expensive.

Gu Qing was one of those red-blooded youngsters who loved swimming. He recalled that most men in his youth, if they wore anything, wore just underwear when they swam. Very few envied individuals were wearing blue, oddly-shaped, triangular swimming trunks.

For those who couldn’t afford a pair of genuine blue swimming trunks, they turned to another material that was readily available—Young Pioneers’ red scarves. A makeshift swimming trunk could be made from two scarves sewn together, with a knot on the right side.

In the 1960s, most women’s swimsuits were made of thick, stiff cotton. They weren’t very comfortable, or popular. The design changed when a thinner, more flexible style was introduced in the early 1970s. These new suits were outfitted with “bubbles (泡泡泳衣),” tiny rubber bands sewn in the lining. They made the swimsuits somewhat elastic, but still quite heavy when wet. All of these suits were either in red or blue. As a result, looking for your friends on a crowded beach could be pretty hard—everyone looked the same.

In the 1980s, amid sweeping economic reforms, new technology and textiles were imported. The latest swimsuits made use of these new materials, and Chinese women could finally get rid of their heavy, ridiculous bubble suits. But not everyone was eager to do this.

Some of the new suits, many felt, were too revealing. They actually showed women’s curves—and this was new.

For years, Chinese women had been working alongside men as equals. During Mao’s time, women were told to cast aside their traditional gender roles. Men and women would wear the same clothes, and take on the same tasks. “Women hold up half the sky,” Mao had said. During this time, showing too much of your body was thought to be too “Western.”

This is why, years afterward, most people were still more comfortable in their wrinkled, concealing swimsuits.

But then came 1986, which changed everything. This was to be remembered as the “bikini year.”

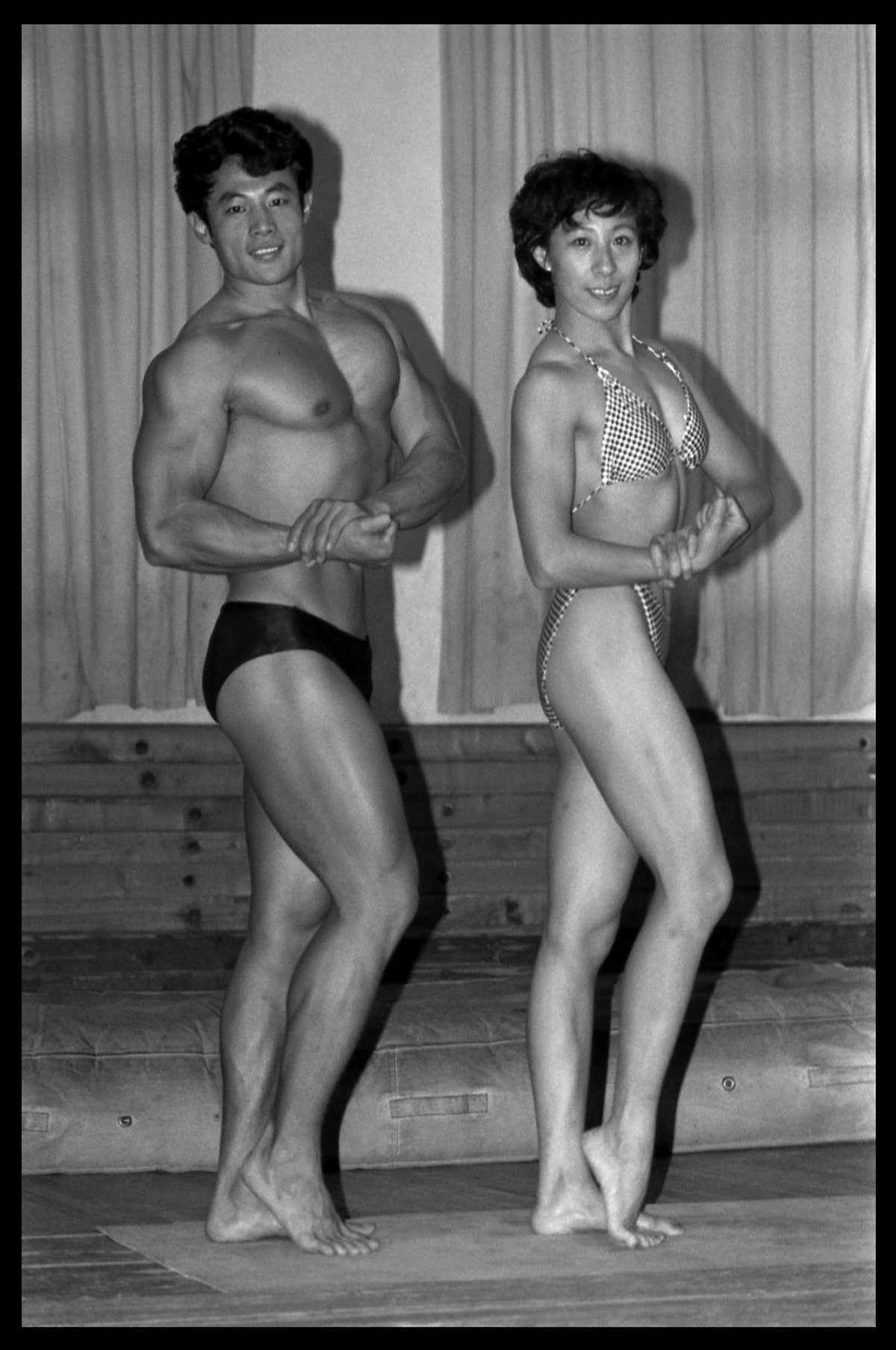

The previous year, China became a member of the International Federation of Body Building. Prior to this, Chinese athletes wore one-piece swimsuits during the contests. However, according to Federation rules, female contestants had to be dressed in bikinis. This would allow judges to best evaluate the quality and tone of the contestants’ muscles.

Though the National Sports Bureau asked the Chinese athletes to dress in bikinis, local organizing committee members were afraid to upset the status quo. Across the nation, many meetings were held discussing this. Still, the matter resulted in indecision. Should they wear bikinis?

Finally, four female Guangdong contestants made the move, donning bikinis at a national bodybuilding competition in Shenzhen in 1986. These bodybuilders were trained under a private coach—Xiong Guohui, who owned his own gym. Maybe this is why they acted so boldly.

Citizens were horrified. Some of the contestants’ parents even threatened to disown their daughters. After the first show, someone called the public security bureau, calling the competition “pornography.”

China was changing. For whatever reason, maybe wanting to project a more international and liberal image, the Administration of Sports ultimately supported Yuan and his bikini-clad athletes.

The bikini had made its way into China, 40 years after its invention in France. The event was one of the breaking news stories of that year.

In 1989, Beijing’s first karaoke club opened, and within a year, the KTV trend had exploded. Small music companies would shoot their own unauthorized low-budget music videos, and most of these were shot on beaches. They usually featured a young woman in a bikini. Her hair would be in the latest style, her scarf would be waving in the tropical wind, and maybe she’d be flirting with a tanned man under coconut trees.

People were no longer looking at the women of Mao’s era, “holding up half of the sky”; they weren’t coal miners or metal welders wearing work clothes. They weren’t wearing cotton one-piece swimsuits either. They had become objectified.

That’s when we knew that times had really changed.

This is a story from our archives: It was originally published in May 2010 in our issue “Traditional Chinese Medicine,” and has been lightly edited and updated. Check out our online store for more issues you can buy!