From denoting various levels of illness to the “Gods of Plague,” 疒 is a radical you need to know in sickness or health

The wave of Covid-19 outbreaks sweeping across China may be easing, but in the meantime, it has given birth to many memes and jokes about the virus, its symptoms, and its treatment on the internet. None of these discussions would have been possible without a useful radical to know in the Chinese language: 疒.

Chinese discourses about disease can be traced back to more than 3,000 years ago. Written records of disease could already be found among the bone and turtle shell inscriptions of the Shang dynasty (1600 – 1046 BCE), and the radical 疒 could already be seen.

In oracle bone inscriptions, 疒 looks like a sweating person lying on a bed, which reflects how people of that time understood illness. The ancient Analytical Dictionary of Chinese Characters (《说文解字》) defines it as, “To lean on. People with disease. Resembles a person leaning on a bed (倚也。人有疾病,象倚箸之形).”

Dozens of characters with this radical are still in use today. Two were already used in ancient times to mean “disease.” The first is 疾 (jí). It’s an ideographic character representing a person getting shot by an arrow (矢), which can be used as a noun or a verb. In the Book of History (《尚书》), a historical text believed to be written in the Zhou dynasty (1046 – 221 BCE), one sentence reads: “The king was suffering from illness (王有疾).” As a verb meaning “to fall ill,” it was used in Sima Qian’s (司马迁) Records of the Grand Historian (《史记》) in the first century BCE: “Jianzi fell ill, and couldn’t recognize people for five days (简子疾,五日不知人).”

The other character for disease, 病 (bìng), first appeared in the Warring States period (475 – 221 BCE). It usually referred to diseases that were more serious than 疾. The Analytical Dictionary of Chinese Characters stated: “病,疾加也 (When ji gets worse it is called bing).”

A story recorded in Han Fei Zi (《韩非子》), a philosophical and legal text by Warring States scholar Han Fei (韩非), also showed the subtle difference between the two characters. When Bian Que (扁鹊), a famous physician in the Spring and Autumn Period (770 – 476 BCE), met Duke Huan of the State of Cai (蔡桓公), he found the duke was ill. So he said to the duke, using 疾: “There are some problems with your skin. If you don’t treat it, it will deteriorate (君有疾在腠理,不治将恐深).” The duke replied: “I am not ill.” Bian Que then left. Ten days later, Bian Que met the duke again, and said: “The disease now is inside your muscle. If you don’t treat it, it will get even worse (君之病在肌肤,不治将益深)”—this time using 病. But the duke still didn’t believe him.

Ten days later, Bian Que warned the duke, his disease had already affected his intestines and stomach, but another 10 days after that, he said nothing after examining the duke but just left the room. Puzzled, the duke sent people to ask Bian Que for an explanation, and the physician responded that the disease had already affected the duke’s bone marrow and there was nothing more he could do. Five days later, the duke died. The story was summarized into the Chinese proverb “讳疾忌医 (conceal one’s illness from the physician),” describing people who hide their problems and take no steps to resolve them.

However, Master Lü’s Spring and Autumn Annals (《吕氏春秋》), a historical book written in the Warring States period, recorded “Zipei fell ill and died (子培疾而死).” This passage contains the character “疾,” meaning that 疾 could also refer to a fatal disease—or perhaps, it was a warning that even trifling illnesses can kill. In modern Chinese, 疾, unlike 病, is almost never used by itself, but more often in two-character words like 顽疾 (wánjí, persistent illness), 恶疾 (èjí, malignant illness), and 隐疾 (yǐnjí, “unmentionable illness,” such as a sexually transmitted disease), and of course, 疾病 (jíbìng), a word for disease in general.

Epidemic illnesses in ancient times were called “瘟 (wēn)” or “疫 (yì).” Combining 疒 with the radical 昷, which means warm or hot, 瘟 generally referred to an epidemic that could cause fever. 疫, according to the Analytical Dictionary of Chinese Characters, is what leads to “people all falling ill (民皆疾也).”

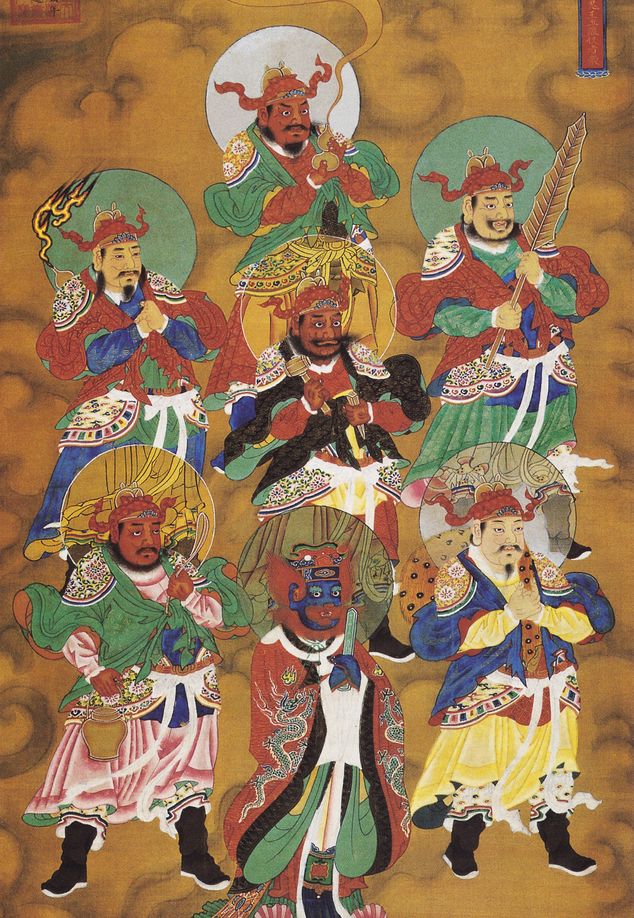

Since the Sui dynasty (581 – 618 BCE), there have been legends about “the Five Masters of Plague (五瘟使者),” also known as “Gods of Plague (瘟神).” It’s said that four gods, called Zhang Yuanbo (张元伯), Liu Yuanda (刘元达), Zhao Gongming (赵公明), and Zhong Rengui (钟仁贵), controlled epidemics during the four seasons, and they were managed by a fifth god, Shi Wenye (史文业). People traditionally worshiped the Gods of Plague in temples, and prayed to them to keep diseases in check. In modern parlance, 瘟神 (wēnshén) can also refer to a person who unleashes disease or disaster around them, like the English term “Typhoid Mary.”

Symptoms of illness are denoted by another 疒 character: 症 (zhèng). “Apply medicine according to the symptoms (对症下药)” is one of the most important principles of traditional Chinese medicine. But it doesn’t mean patients with the same symptoms should be treated with the same medicine. This saying originated from The Records of the Three Kingdoms (《三国志》), which recorded that famous physician Hua Tuo (华佗) wrote different prescriptions to two patients with the same symptoms and cured both of them. Hua Tuo explained that he used different prescriptions because the causes of their symptoms were different. Such a theory was later summarized into the aforementioned Chinese proverb, which also has the broader meaning of “find the key to a problem and use a targeted method to fix it.”

Today, many characters with the 疒 radical are rarely used, and even native Chinese speakers may not know them all. Still, when you spot this radical, it’s easy to conclude that the character refers to illness or problems with the body, like 疟 (malaria), 疡 (ulcer),疣 (wart), 痔 (hemorrhoid), and 癌 (cancer); or symptoms of ill health like “疼 (pain), 痒 (itch), 痹 (numbness), and 瘫 (paralysis).

Given this history, it’s hard to find a nice word that uses the “disease” radical, but there is still an exception—疗 (liáo). It means “treat, cure, and recuperate.” With parts of China still in the grip of the Omicron variant, and millions of people expected to travel home for the Lunar New Year holidays, let’s hope that the Five Masters keep everyone safe.